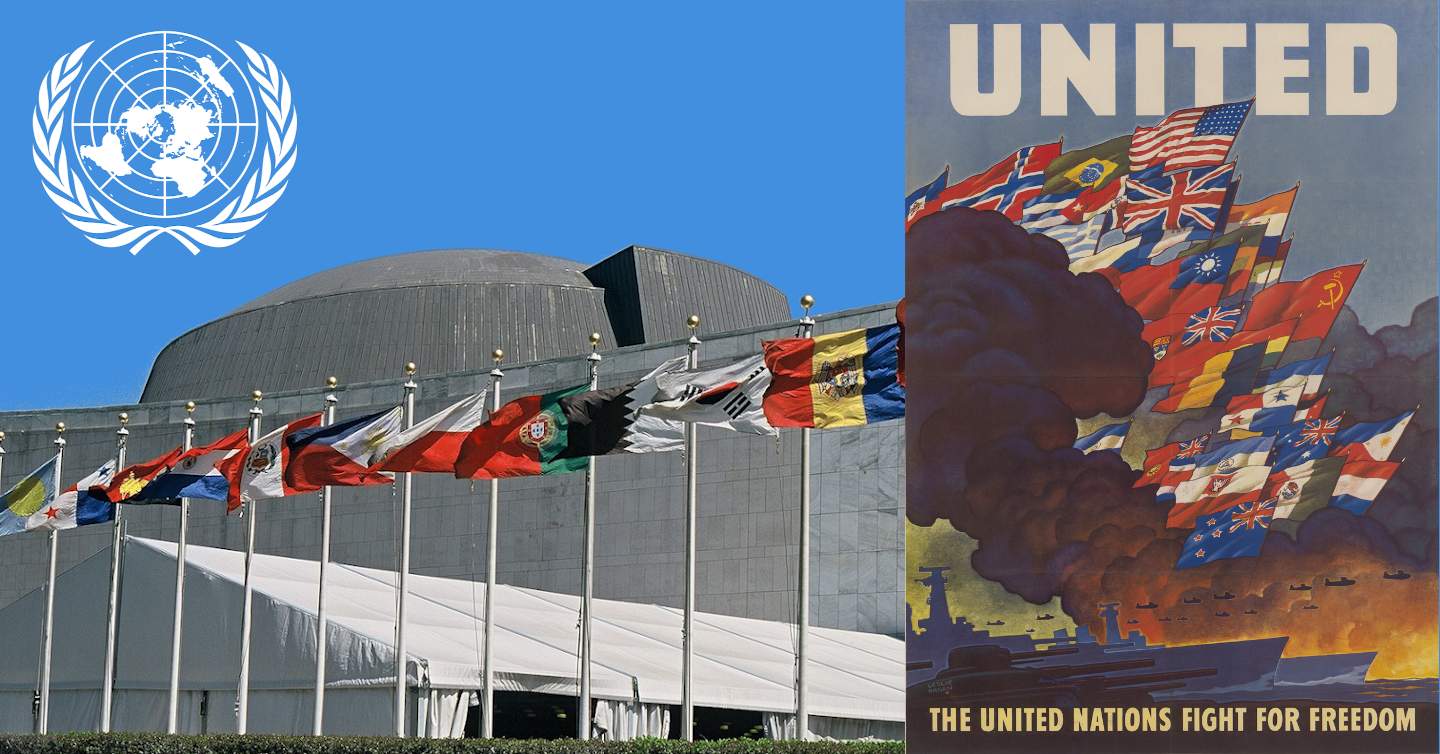

26 COUNTRIES SIGNED THE DECLARATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS ON 1 JANUARY 1942 THAT SUBSCRIBED TO THE PRINCIPLES OF THE 1941 US-UK ATLANTIC CHARTER.

For this Whiteboard we reached out again to several scholars with the following prompt:

What has been the United Nations’ greatest accomplishment since its founding?

Readers are invited to make their own contributions in the comments section.

1. Professor Leigh C. Caraher, U.S. Army War College, Applied Communications Lab

Of all the U.N.’s accomplishments since 1945, perhaps its greatest accomplishment is the millions of lives U.N. humanitarian agencies have saved. The U.N.’s humanitarian mission is enshrined in its Charter: “to achieve international cooperation for solving international problems of an economic, social, cultural, or humanitarian character.” Founded in the aftermath of World War II, U.N. humanitarian agencies, like the World Food Program, United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), World Health Organization, and the U.N. Refugee Agency (UNHCR), continue to deliver life-saving assistance to millions of people affected by conflict, drought, hurricanes, tsunamis, earthquakes, crop failures, and infectious diseases every year.

With the world facing unprecedented levels of population displacement and humanitarian need, U.N. humanitarian efforts are impressive in their scale and complexity. These organizations work with international and local partners in difficult and dangerous places to bring desperately needed food, safe drinking water, medical treatment, shelter, and other relief to vulnerable people. In northeastern Nigeria, the World Food Program provides emergency food assistance to 1.2 million conflict-affected people every month. In Yemen, UNICEF reached more than 700,000 people with emergency water and sanitation services in areas at high risk of cholera in 2019. In addition to the technical assistance it provides to fight the Ebola outbreak in Democratic Republic of Congo, the World Health Organization and its partners are conducting a measles emergency follow-on vaccination campaign to reach 18.9 million children as the country experiences the world’s worst measles outbreak. In Syria, with an estimated 11.9 million refugees and internally displaced persons, UNHCR and the U.N.-related International Organization for Migration provide emergency shelter, non-food items, and other services to those who fled their homes and the host communities that shelter them.

The U.N.’s humanitarian architecture is certainly not without its flaws and challenges. Many humanitarian responses are chronically underfunded. Humanitarian access is becoming more restricted. Humanitarian aid is increasingly instrumentalized by governments. Critics question the operational effectiveness of U.N.-led humanitarian responses as processes and structures grow outdated. Hard questions are being asked about how aid may create dependency or prolong conflicts. Reform efforts are underway as part of the World Humanitarian Summit’s Grand Bargain and the U.N. Secretary General’s Agenda for Humanity. In the meantime, the often-unsung heroes of U.N. humanitarian agencies and their partners will continue to deliver life-saving humanitarian assistance to populations in need.

2. Dr. Richard Lacquement is the Dean, School of Strategic Landpower, U.S. Army War College.

The United Nations’ greatest accomplishment has been its success in winning the last war among great powers and then preventing future great power war.

26 countries signed the Declaration of the United Nations on 1 January 1942 that subscribed to the principles of the 1941 US-UK Atlantic Charter. The signatories, to include 21 more nations that added their adherence during World War II, represented the alliance that successfully defeated the Tripartite Pact of Germany, Japan and Italy. Before the fighting of World War II ended, an expanded assembly of 51 nations created and signed the Charter of the United Nations that placed international peace and security—especially the prevention of armed aggression of any country against another—at its core. The United Nations has played a major role in preventing great power war ever since. It helped keep the Cold War cold (such as its contributions to tamp down escalation in dangerous moments of great power tension surrounding the Korean War, the Cuban Missile Crisis, and the 1973 Arab-Israeli War) and worked to check the escalation of other conflicts through peacekeeping, conflict prevention, peacemaking, peace enforcement, and peacebuilding missions that often included multinational forces under U.N. flag.

The mechanisms of the United Nations’ signal success are complex. There have certainly been other wars since the 1945 U.N. Charter signing, but, thankfully, no great power war like the cataclysmic one that called the U.N. into existence. To me there are three important aspects of the United Nations that contribute to the absence of great power war since World War II. First is the basic principle to prevent future war that is at the heart of the U.N.’s creation that conveys a collective moral authority regarding the legitimacy or illegitimacy of the use of force by any state against another, and, more recently, even against their own populations. Second is the UN’s role as a vital forum for international diplomacy among the great powers, particularly within the context of the United Nations Security Council. Third is the practical incentive to avoid conflict and reap the benefits of cooperation that underpin the many functional elements of the United Nations System (such as endeavors for sustainable development, global health, food security, human rights, refugees, migration, telecommunications, decolonization, civil aviation among many others).

The U.N.’s noble accomplishment in ending great power war is one of the highlights of history.

3. Dr. Alexandra Middlewood, PhD, Assistant Professor of Political Science, Wichita State University

The United Nations has faced many challenges since its founding, particularly decreasing confidence in global governance and global institutions in recent years. Nevertheless, the United Nations has undoubtedly made significant contributions to its founding goal of promoting peace and security. Its greatest accomplishment, however, belongs not to the Security Council, but to the General Assembly.

Resolutions passed in the General Assembly may lack the binding enforcement of those passed in the Security Council, but they hold much more political influence. Only in the General Assembly does every Member State have an equal seat at the international table. Therefore, resolutions reflect the views of the international community as a whole, and not only the attitudes of those who hold coveted seats on the Security Council. The General Assembly has debated and passed significant documents that influence both international and domestic politics. For example, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was passed by consensus in the General Assembly, with only eight member states abstaining. While not legally binding, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights has nonetheless become cemented in international law and has been consistently invoked by Member States for various human rights issues.

Resolutions have also been used to make symbolic political statements by the General Assembly. For example, in 2012, the General Assembly overwhelmingly voted in favor of a resolution on the Status of Palestine in the United Nations, recognizing Palestinian statehood and upgrading their U.N. status from observer entity to non-member observer state. While only the Security Council can grant full membership and voting rights, this General Assembly effectively made a symbolic statement to the international community on the question of Palestinian statehood.

The case of China and Taiwan also has political influence. The Republic of China (Taiwan) was an original member of the U.N. until 1971 when representation was replaced by the People’s Republic of China via General Assembly Resolution 2758. In 1993, the Republic of China began a campaign for U.N. membership, but was denied. The U.N. argued that Resolution 2758 states the People’s Republic of China represents the whole of China, of which Taiwan is a part. Denial of membership to Taiwan symbolized the United Nations had made a political statement to affirm the One China Policy.

Undeniably, the General Assembly consistently uses its resolutions to make symbolic political statements about international and domestic politics. Historically, no other global institution has had the capacity to wield such political influence at the international level. As such, this is the United Nations’ greatest accomplishment since its founding.

4. Dr. Daniel J. Whelan, Ph.D., Dr. Brad P. Balz and Rev. William B. Smith Odyssey Professor of Politics & International Relations, Hendrix College

The most significant accomplishment of the United Nations since its founding has been the codification of humanitarian and especially human rights law. Humanitarian law has a longer history that predates the United Nations (the original Geneva Convention of 1864 and the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907). But human rights law is a creature of the U.N. At the San Francisco Conference (April – June 1945) a number of smaller states and an array of (mostly American) NGOs lobbied to include “the protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms” among the purposes of the new world organization. The U.N. Charter that was adopted at San Francisco empowered the new Economic and Social Council to create a human rights commission, whose first job would be to draft a bill of human rights.

The U.N. adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights on December 10, 1948, without a single dissenting vote. The Universal Declaration holds the world record as the most translated document in human history, currently at 523 languages. The text of the UDHR has been incorporated into many constitutions throughout the world, and stands, in its own words, as a “common standard of achievement for mankind.”

While the Declaration was not formally law (it is not a treaty), its core principles have been further expanded in core human rights conventions that do carry the force of law, among them the two International Human Rights Covenants (on Civil and Political Rights, and on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights); the Conventions on Racial Discrimination, Women’s Rights, the Rights of the Child, and Torture. The Genocide Convention made genocide and related practices a crime under international law. The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court further defines war crimes and crimes against humanity, and the court is empowered to open investigations and try cases that are duly placed on its docket.

Some might object that because the U.N. lacks any significant enforcement power, such law is practically meaningless. But that type of positivistic “purity” misses the power of human rights law, which creates real obligations to which states have consented to be bound. And imagine a world without human rights or humanitarian law. Governments could credibly claim that there is nothing “illegal” about committing human atrocities. It’s one thing to live in a world where human rights are violated, or crimes committed, sometimes with impunity. It would be quite another for such things to happen and there was nothing that made such actions anything other than a simple act of state carried out under the cloak of sovereignty.

5. Dr. Jacqueline Whitt, Professor of Strategy, US Army War College; Editor-in-Chief of WAR ROOM, and Associate Executive Director of American Model United Nations

When it comes to the United Nations, the Security Council steals most of the spotlight—and attracts most of the critiques about creeping world government, black helicopters, ineffectiveness, being undemocratic, and cost. A more informed critic might take aim at the universal-membership General Assembly, or perhaps the Secretariat (the $16 million in unpaid parking tickets in New York City offers some evidence of the problems), decrying it as bloated, ineffective, and expensive. There’s plenty of fair criticism to go around.

But if you peek a little deeper into the org chart, you’ll find a host of specialized and technical agencies. As the United Nations has grown and increased in complexity, the international community leans more heavily on these expert bodies. We hear a great deal more than we used to about the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), the International Telecommunications Union (ITU), and the Universal Postal Union (UPU). This makes sense. Many of today’s global problems are highly technical—from internet governance to dual-use chemical regulations and civil aviation. These problems are not well-suited for discussion in the General Assembly, where diplomats tend to be generalists. These problems demand the attention of specialists, including private sector representation.

In 2012, the Rio+20 Summit included more input from civil society and private sector actors than any previous U.N. meeting. While it seemed anomalous at the time, it actually represented several decades of changing practice at the United Nations. Beginning in the mid-1990s, a growing number of U.N. bodies and agencies have created formal mechanisms for the involvement of civil society. These efforts include partnerships like the U.N. Global Compact, formal organizations such as the International Labour Organization (which includes formal representation from business and labor), and expert bodies such as the Committee of Experts on Public Administration (CEPA).

The United Nations today is not the United Nations of 1945. Nor is the international environment. One of the organization’s greatest strengths has been its ability to adapt and evolve as the global environment has changed. Far from being ineffective, outdated, or unnecessary, we should marvel at how much it has done and how much it can continue to do with the support of the international community—states, international organizations, non-governmental organizations, corporations, and private citizens alike.

Dag Hammarskjöld, the second Secretary-General of the United Nations wrote in 1955, “The U.N. is not just a product of do-gooders. It is harshly real. The day will come when men will see the U.N. and what it means clearly. Everything will be all right—you know when? When people, just people, stop thinking of the United Nations as a weird Picasso abstraction, and see it as a drawing they made themselves.” The United Nations today is full of real people doing real work around the world. This work is often visible, and it has dramatically improved the human condition in the last seventy years. Just as often, though, the work is largely invisible, but critical in making our modern world work.

The views expressed in this Whiteboard Exercise are those of the contributors and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, U.S. Army, or Department of Defense.

Photo Description: Poster created during the Second World War (1943), according to the Declaration of the United Nations of 1942. The Poster, created by United States Office of War Information and made by United States Government Printing Office. The poster features the flags of those countries or governments-in-exile that pledged to support the Allied effort (beginning from the top-left corner, and continuing in rows from left to right: Haiti, Norway, Brazil, the United States, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, the United Kingdom, Greece, Guatemala [behind the British Flag], South Africa, Czechoslovakia, China, Ethiopia, Luxembourg, Canada, the Soviet Union, Belgium, Bolivia, Yugoslavia, Honduras, Panama, Iraq, India, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Australia, the Philippines, Poland, Mexico, The Netherlands and New Zealand) above the on-going war machine that the United Nations represented. The absence of the Free French flag is unusual. This poster is important because it represents the origins of the United Nations as a wartime alliance (before it was a concrete organization). As a work of Office of War Information, a branch of the United States Federal Government, this work is in public domain. (per Wikimedia Commons)

Photo Credit: As a work of Office of War Information, a branch of the United States Federal Government, this work is in public domain. U.N. photo and Emblem via Wikimedia Commons

Other releases in the “Whiteboard” series:

- THE ADMINISTRATION’S TOP FOREIGN POLICY PRIORITY (A WHITEBOARD)

- AFTER 2020, WHAT’S NEXT? (A WHITEBOARD)

- IMAGINING OVERMATCH: CRITICAL DOMAINS IN THE NEXT WAR (A WHITEBOARD)

- THAT ONE MOST IMPORTANT THING: (A WHITEBOARD)

- SHALL WE PLAY A GAME?

(WARGAMING ROOM) - WAR(GAMING) WHAT IS IT GOOD FOR? (A WHITEBOARD)

- LEADERSHIP ROLE MODELS IN FICTION REVISITED: (A WHITEBOARD)

- WHAT GOOD IS GRAND STRATEGY? (A WHITEBOARD)

- THE UNITED NATIONS’ GREATEST ACCOMPLISHMENT: (A WHITEBOARD)

- LEADERSHIP ROLE MODELS IN FICTION: (A WHITEBOARD)

The United Nations (UN) has several extremely important suborganizations. Especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, the World Health Organization (WHO) is possibly the most important creation of the UN. Ironically, President Wilson, who ultimately sacrificed his health during his campaign to popularize the predecessor organization – The League of Nations, helped to spawn a Health League way beyond his impressive vision for the future. Health has increasingly become a global problem – along with the exacerbating related problems of poverty, lack of education, and political turmoil. Other UN organizations are quietly working wonders behind the scenes along with the WHO: the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), and the United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC). The UN has also created some even lesser known suborganizations, but arguably no less important, such as the International Court of Justice. Social and legal justice, not to mention fair and just elections, are achievable, but not without oversight and foresight! A well-known, but not normally viewed suborganization is the Secretariat. Secretary-General António Guterres issued a cease-fire entreaty on 23 March 2020 asking governments and state-less groups to halt hostilities and create create “corridors for life-saving aid.” Time will tell if hostilities will actually cease, but having some form of planet government and communication is certainly comforting and hope inducing.

Ironically, the United States had to struggle with the Articles of Confederation before formulating the much more robust U.S. Constitution. In a similar organizational learning curve process, the League of Nations (without the membership of the United States) helped to give birth to the United Nations (UN). The UN in many ways goes way beyond being an international debating and translating service; the UN has created an impressive list of sub-organizations in addition to the WHO, as noted above; this mini-essay, however, focuses primarily on the WHO. Paradoxically, during the worst pandemic recorded in World History, the Black Death of the 13th century (from 1346 through 1350), biological warfare exacerbated the 4-year long crisis as political and military enemies used contaminated substances to spread the disease to their enemies. According to Reilly (2009), “the Mongol army hurled plague-infected cadavers into the besieged Crimean city of Caffa, thereby transmitting the disease to the inhabitants …” (p. 424). We can only hope and pray and negotiate in the 21st century for traditional enemies to team together to combat COVID-19 rather than perpetuating it through intentional or negligent spreading of the disease. Perhaps revisiting nightmares of the past can help us formulate vital visions for the future.

During times of peace and prosperity, we enjoy the global view of the Summer and Winter Olympic games and the worldwide excitement of the World Cup, yet as Americans we seem myopic once a year when we still cheer on our favorite baseball teams as they compete for trophies and sponsorships for the poorly named “world series.” COVID-19 is a global challenge on a scale that approaches the Influenza pandemic of 1918 and hopefully will not reach the depths of destruction of the Black Death of 1346-1350. Once we add COVID-19 to the pages of history, we will know if we rose to the challenge of a 21st-century pandemic or if we succumbed to partisan squabbling and international competition rather than global collaboration.

Reference

Reilly, K. (2009). Worlds of history: A comparative reader (3rd ed.). Boston, MA: Bedford/St. Martin’s