‘if only the politicians had let us do our jobs’ remains a powerful military narrative

We thank you for the overwhelming number of submissions in response to our question:

What is the most important insight about war or strategy that we gain from the study of the First World War?

We will publish the top responses in no particular order over two posts. The second installment will run on 14 December. Click here to review the prompt and the views of historians and scholars.

1. PAUL SMITH, LTC, U.S. ARMY

An insight from World War I with critical relevance today is the disastrous impacts of nationalism. Europe in the early twentieth century saw rising nationalism swept through the continent. This led to increased trade competition, networks of complicated alliances, and social and political foment. The result was a massive global war, the likes of which the world had never seen.

100 years after Remembrance Day, we see an environment that eerily resembles that of pre-World War I Europe. The stage appears set for another global reordering, with consequences that could affect the world either through military action or through a disruption of the rules-based international order. Part of the political upheaval stems from the perceived decline in power of the United States. America’s own policies reinforce this by weakening alliances and spreading messages of nationalistic isolationism in foreign policy.

This loss of power has opened the doors for autocratic leaders in China and Russia to push for significant changes to the current political order. These countries use nationalism to mask domestic issues, but that same fervor is a double-edged sword. As governments seek to build national pride, any embarrassment in international relations may incite the people to rally against their own governments. For ruling elites, a conflict may be the lesser of two evils, since political accommodation could result in a collapse of the government making war more likely today than in years past.

History demonstrated that when the United States adopts a nationalistic or isolationist foreign policy, the likelihood of war increases. As Angela Merkel recently said, “The First World War showed us what kind of ruin isolationism can lead us into. And if seclusion wasn’t a solution 100 years ago, how could it be so today?”

2. MARKUS MEYER, LTCOL, GERMAN ARMED FORCES

“In war, politics keeps its mouths shut until strategy allows it to speak again” – scribbled on the margins of a late 1915 newspaper article by the German Emperor, Wilhelm II.

Considering the experience of World War I, one of the clearest insights was how the dysfunctional relationship between political and military leadership in Germany led to disaster. Time and again, German Generals and Admirals forced their political leadership to accept seemingly inevitable military imperatives as a basis for strategic decision-making. For example, Germany felt trapped between France and Russia as war seemed inevitable, and thus needed Belgium territory to enable a swift battle of annihilation against France and demanded unrestricted submarine warfare to strangle Britain.

It is deeply ironic that it was the German military that disregarded Clausewitz’s dictum of “war as a political” act so deeply. This disregard for the other instruments of national power ensured that the German strategy – if there was anything worth calling a grand strategy – was deeply flawed. Political considerations were sidelined. Only when the war was lost did the military leadership hand back control – and blame – to the political institutions.

The lessons of this seem obvious:

- Understand that war is a complex combination of military, economic, and political challenges.

- Employ and coordinate all instruments of national power to create holistic options for conflict solution.

- Don’t accept the transfer of political decision-making to military institutions during conflict.

But, “If only the politicians had let us do our jobs,” remains a powerful military narrative during many conflicts of the modern era. Maybe a look at World War I can help us to understand that war remains to be a political act. Therefore, assessing military demands against demands of a grand strategy and retaining political control of war is as vital as it was in the early twentieth century.

3. MICHAEL PIELLUSCH, ARGOSY UNIVERSITY

Many military lessons learned end up being unlearned and forgotten. But World War I provided the basis for a multi-domain view of war that has benefited the U.S. military ever since. In the century since, the U.S. has obtained and sustained mastery of the air, sea, and land domains, viewing it as the foundation of military and strategic dominance.

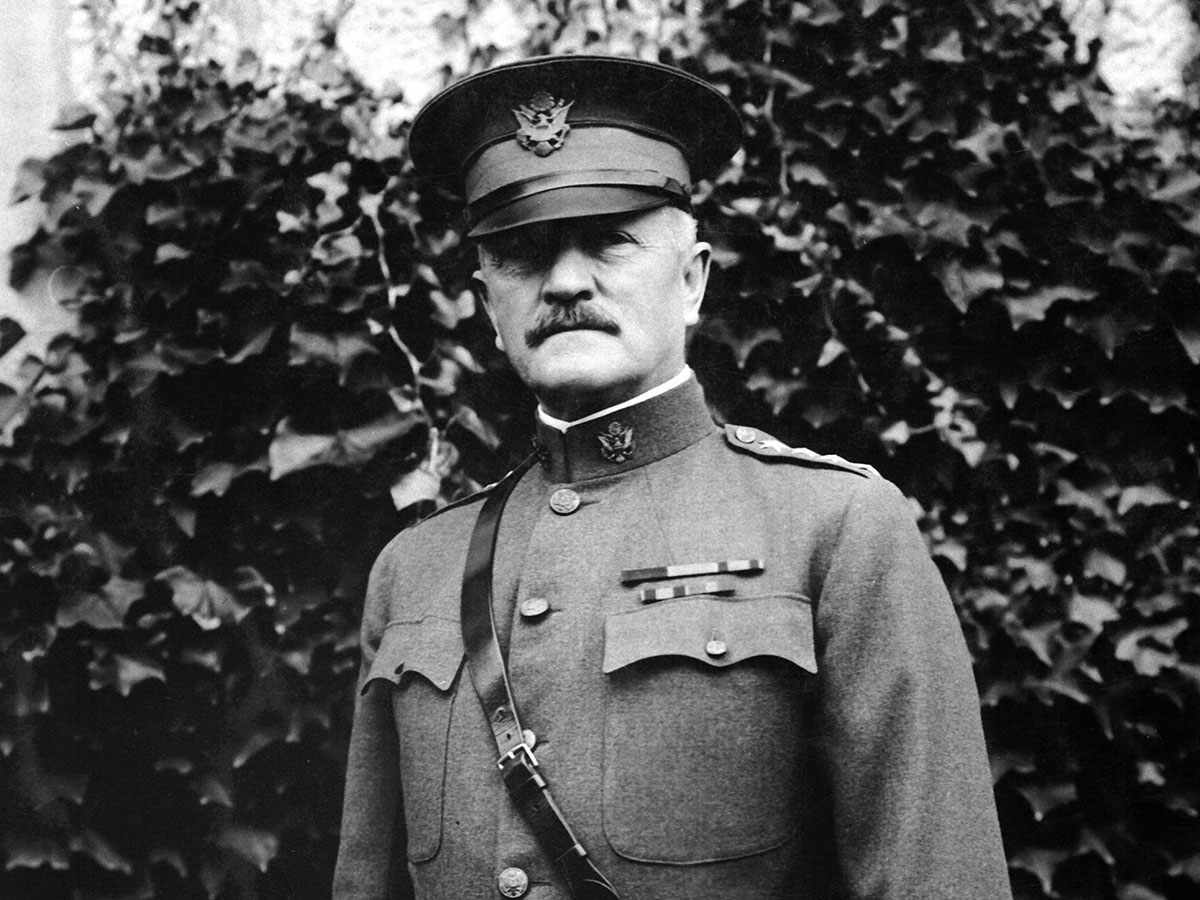

In the air, ace pilots established a new culture and a new method of coordinating land actions with aerial support and intelligence observations. Mechanic magicians kept the American eagle airborne. On land, the Great War brought us legendary warriors such as Sergeant Alvin York and iconic leaders such as General Pershing. Eclipsing the stalemate and the trench warfare of increasing stagnation, Pershing resisted requests for the Americans to merely become replacements in a war of attrition. Sergeant York epitomized and foreshadowed the trend toward Special Forces, unforgettably demonstrating that a small force, or even one outstanding soldier, can achieve decisive results despite technological disadvantages. On the sea, convoys of battleships, destroyers, troop carriers, and support vessels matched wits with the U-boat fleet and developed maneuvers and tactics that gradually made the Atlantic more hazardous to German submarine crews than to the troop carriers and other convoy elements. Techniques such as darkened ship, zigzag evasion steaming, and dead reckoning navigation helped the Allies develop and refine sea dominance while honing navigational and ship-handling skills.

One hundred years after the Armistice, military aircraft, aircraft carriers, and other tools of warfare have advanced exponentially. Consequently, lethality based on air, land, and sea dominance is a culture and tradition entrenched in legends and legacies of the best and brightest of the Great War.

Lack of adequate preparation prior to America’s entry into the war in 1917 required the army to undertake a major and rapid transformation

4. CRAIG BONDRA, COL, US ARMY

The First World War provides a stunning example of the importance of the need to study and develop an understanding of how the character of war changes. WWI was fought on a level of violence, intensity, and vastness of scale never before seen in history. Battles involved hundreds of thousands of troops fighting over large areas of front that lasted weeks and months. The deadliness of the WWI battlefield resulted from the immense amount of firepower that could be brought to bear. Armies on both sides had to learn, at great cost, how to incorporate and coordinate these new weapons and technologies.

This was particularly true for the U.S. Army as it was unprepared for the type war in which it found itself. As a result, it was forced to transform from a regimental-centric constabulary force to one capable of fighting as divisions, corps, and ultimately armies on a modern industrial battlefield. The lack of adequate preparation prior to America’s entry into the war in 1917 required the army to undertake a major and rapid transformation and modernization effort to field a force able to deploy to and succeed in Europe. There were, as a result, serious shortfalls in doctrine, organizational structure, leadership, and training. These issues hampered the readiness of the soldiers of the American Expeditionary Force for the fighting occurring on the Western Front in 1918. With little time to prepare before being committed into battle, the “doughboys” had to learn as they fought.

5. VINCENT DUEÑAS, MAJ, US ARMY

The study of the Great War’s effect on society reminds us that war is a human endeavor that shares principles with nature. War’s characteristics can be understood through first-principle thinking, which breaks down something into foundational concepts and then puts them back together. Self-organized criticality (SOC) is one such principle, aiding us in understanding the causes of WWI.

SOC states that the elements that make up some complex systems may lead to certain critical attractors, including catastrophic outcomes. Thus, shifting tectonic plates produce tension that is only released through earthquakes, or the growth of forests produces massive stocks of fuel that are consumed in wildfires. “Fingers of instability” arise preceding the catastrophic outcome, offering evidence that nature perpetually reverts to a critical state in which catastrophes are imminent. The catastrophe of WWI may have been a natural phenomenon of our complex human system, with national competition and an intricate system of alliances producing fuel for the eventual conflagration.

The “Powder Keg of Europe” resulted from aggression by the German and Austro-Hungarian political leadership, which was undeterred by the alliance built to dissuade conflict. Remarkably, however, it was a non-state actor – the Serbian “Black Hand” group – which started the war by killing the Austro-Hungarian Archduke. The deteriorating condition in the Balkans created a finger of instability that initiated the cascade of protocols intended to prevent war, but in fact caused it by default. Self-organized criticality gives the outbreak of World War I a sense of inevitability. Indeed, it makes one wonder whether catastrophic war is indeed an attractor value in human history.

Reducing the likelihood of global catastrophes likely requires lethal and non-lethal actions against “fingers of instability” in the global commons. Defining and identifying true “fingers of instability” to apply appropriate measures of force to achieve conflict minimization is the priority. Persistent peace has no precedent in history, and physics offers no example of equilibrium by which we can perceive the observed world, but thinking in first principles offers insights on the natural characteristics of war.

The views expressed in this Whiteboard are those of the contributors and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, U.S. Army, or Department of Defense.

Photo: Portrait of General John J. Pershing at General Headquarters, Chaumont, France

Photo Credit: U.S. Army Signal Corps photo, public domain

Other Releases in the Whiteboard series:

- THE ADMINISTRATION’S TOP FOREIGN POLICY PRIORITY (A WHITEBOARD)

- AFTER 2020, WHAT’S NEXT? (A WHITEBOARD)

- IMAGINING OVERMATCH: CRITICAL DOMAINS IN THE NEXT WAR (A WHITEBOARD)

- THAT ONE MOST IMPORTANT THING: (A WHITEBOARD)

- SHALL WE PLAY A GAME?

(WARGAMING ROOM) - WAR(GAMING) WHAT IS IT GOOD FOR? (A WHITEBOARD)

- LEADERSHIP ROLE MODELS IN FICTION REVISITED: (A WHITEBOARD)

- WHAT GOOD IS GRAND STRATEGY? (A WHITEBOARD)

- THE UNITED NATIONS’ GREATEST ACCOMPLISHMENT: (A WHITEBOARD)

- LEADERSHIP ROLE MODELS IN FICTION: (A WHITEBOARD)