maybe the grandiose version of strategy is overrated. A nation that muddles along may nonetheless move forward; and America has done just that.

This is the second of two response posts for the Whiteboard on the U.S. military’s strategic proficiency (or deficiency). Thanks to everyone who submitted responses. The next Whiteboard is coming soon. Stay tuned!

Based on the judgment of the editorial board, the following (in no particular order) were among the best responses to the following question:

Some analysts claim that the United States is tactically proficient, but strategically deficient. How sound is this critique?

-

Chris Bolan, U.S. Army War College Faculty

As Socrates presciently noted nearly 2,500 years ago, “The beginning of wisdom is the definition of terms.” As long as the concept of strategy is largely confined to military matters, the U.S. will remain a physically dominant opponent who can be bested by cagey athletes with a wider range of talents.

Tactical or operational military superiority, while undoubtedly desirable, does not alone guarantee strategic success. I recommend beginning the debate over U.S. strategic competencies by studying Liddell Hart’s critique of earlier strategists including the famed Carl Clausewitz for their narrow conception of strategy as “the art of the employment of battles as a means to gain the object of war.” Hart proposed a more expansive vision of strategy as the coordination of “all the resources of nation, or band of nations, toward the attainment of the political object of the war.”

Hart’s definition makes it clear that today’s strategists must be conversant with the full range of tools available to U.S. policymakers and any potential coalition partners. Moreover, strategy must fully integrate traditional elements of hard military and economic power alongside soft power tools smartly engaging diplomacy, information, influence, and values.

Just as American military dominance was incapable of securing political victory in Vietnam, today’s massive defense budgets will not guarantee durable success absent a broad conception of strategy that also accounts for, develops, and intelligently employs the non-military instruments of power.

-

Lieutenant Colonel Chad Storlie, U.S. Army Retired, former Special Forces officer

The U.S. military is tactically and strategically proficient in the wars that the U.S. military wants to fight. For adversaries that choose to fight the United States in a manner that reflects the U.S. preference for conflict (large, open, force-on-force, in non-populated areas), the U.S. tactics and strategy are successful. Any historical example over the past 30+ years reflects this dual success. Operation Desert Storm, the initial ground invasions of OIF 1 and OEF 1, the 1989 invasion of Panama, the 1983 invasion of Grenada, and the U.S. support of the NATO air campaign in Bosnia that helped secure the IFOR / SFOR involvement in Bosnia were all tactical successes and initially strategically successful.

The U.S. military falters when adversaries choose to fight in a manner that does not allow the United States to prosecute tactical and strategic objectives in a way that it prefers. The Sep-Oct 1993 street battles in Mogadishu, the attempts to bring a lasting secure peace to Iraq and Afghanistan, and the U.S. involvement in Lebanon in 1983 that culminated in the truck bombing of the U.S. Embassy and the Marine Barracks are all examples of the U.S. being tactically and strategically unsuccessful because of a failure to adapt to adversaries’ preferred ways of fighting.

Strategy must align resources, goals, and elements of national power against an adversaries’ preferred way of fighting. The U.S. needs to learn, embrace, and enforce fighting at the tactical and strategic levels in a way that hinders an adversary’s ability to fight the war it prefers to fight. Strategy must apply and align resources, goals, and elements of national power against an adversaries’ preferred way of operating and fighting. The historical lessons of Iraq, Vietnam, Afghanistan, Somalia, and Lebanon are that the U.S. needs to fight at the tactical level in a manner that defeats the adversaries’ tactics. A progression of this kind of tactical success delivers strategic success.

Military strategic success is not fighting the way the U.S. prefers to fight. Military strategic success is fighting in a way that proves enduring and effective against enemies’ preferred ways of fighting.

The tactical and strategic are not discrete, independent levels that can be evaluated exclusive of each other. After all, war is more than the sum of its conduct.

-

Doug Douds, U.S. Army War College Faculty

The answer is “yes” and perhaps “no” in both cases. The U.S. is tactically dominant. It is effective across the warfare spectrum as we have known it. Moreover, when not effective, the tactical level is populated with professionals who by organization and culture learn and adapt to reestablish tactical dominance. It is the nation’s ability to connect that tactical prowess to strategic political outcomes that is inconsistent, if not dubious.

In the aftermath of World War II and in elements of the Cold War, the U.S. demonstrated the ability to connect warfare and politics. However, we can also see numerous examples of a failure to connect tactical prowess with even short-term strategic outcomes, let alone lasting ones. At the War College, we teach that the connective sinew of operational art synchronizes tactical activities in time, space, and purpose that has fallen short. If so, we need to start questioning a system that produces tactically dominant and successful officers who, when elevated to senior levels, fail to employ operational art effectively. This is a damning indictment of that tactical system.

If strategy is the problem, then perhaps as a nation flush with means, possessing numerous and varied ways, and without an immediate, existential threat, we simply lack discipline to make hard strategic choices. When everything is important, nothing is. Ultimately, strategy is about making choices in context. Absent clear priorities, strategy fails to exert its imperatives on the operational and tactical activities required for its success. Lacking a visionary leader or a crisis, the U.S. defers hard choices and the direction inherent to them. As a result, the nation strategically muddles along. And this is the counter-argument: maybe the grandiose version of strategy is overrated.

A nation that muddles along may nonetheless move forward; and America has done just that. If we accept that we cannot predict the future and the idea of a strategy is not to get it too terribly wrong, perhaps our muddling strategic acumen suffices … for now.

-

Lieutenant Colonel Robert Mihara, Army Strategist, U.S. Army North (Fifth Army)

The distinction between tactical and strategic proficiency is at once helpful and misleading. It is helpful in that it can assist one in assessing the U.S. military’s performance in the phenomenological domains of war – the material and the abstract. Differentiating between tactical proficiency and strategic deficiency can inform carefully scoped, internally oriented, questions of structure, human capital, and processes. Yet, the distinction is also misleading in that it bifurcates what is practically speaking a unitary issue, i.e., U.S. proficiency in the singular phenomena of war.

The tactical and strategic are not discrete, independent levels that can be evaluated exclusive of each other. After all, war is more than the sum of its conduct. As a phenomenon, war includes the rational and irrational forces that supply the animus of armed conflict as well as determine the evolution of that conflict to its resolution.

If proficient in war, the U.S. military will have consistently demonstrated its competence to assess the fundamental nature of its wars and, having done so, committed itself to those wars in proportion to American interests. It should then have succeeded in translating its understanding of each war’s nature, the U.S. national interests in context, and the means available into efficacious campaigns.

Yet, the U.S. military has struggled to translate its technical ability into a tactical proficiency that is relevant to necessary strategic outcomes. In its wartime struggles, the military has embraced fatalism when facing the intractable, perpetually looking for the proverbial corner to be turned. The U.S. military is not exceptional in these difficulties, but Americans should not indulgently claim refuge in tactical proficiency.

One can only disingenuously claim that technical prowess, and perhaps martial virtue, are sufficient to assure proficiency in war. Militaries that narrowly rely on the primacy of action will eventually be betrayed by it.

The views expressed in this Whiteboard Exercise are those of the contributors and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, U.S. Army, or Department of Defense.

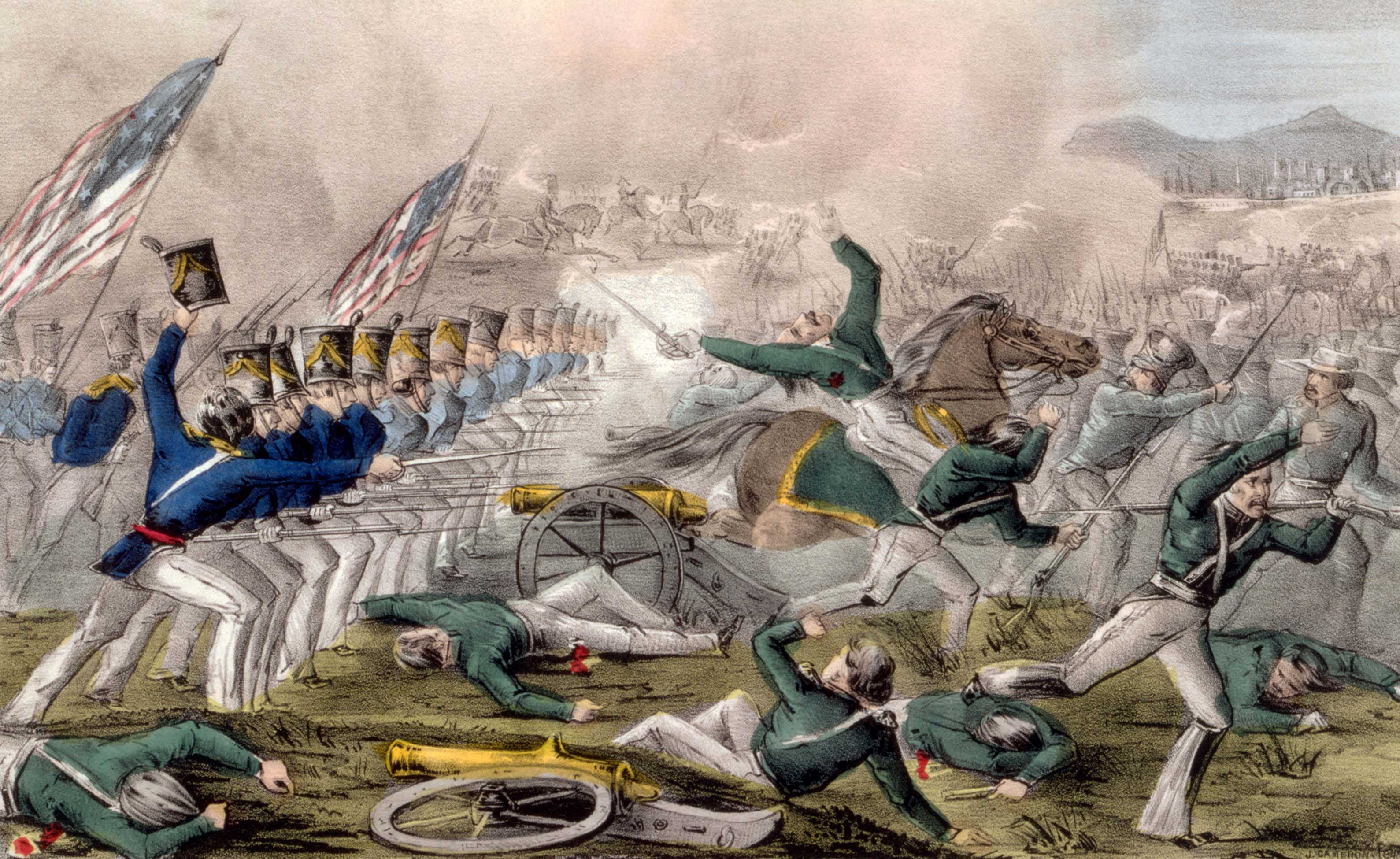

Image: Hand tinted lithograph titled “Battle of Churubusco–Fought near the city of Mexico 20th of August 1847” by John Cameron, published by Nathaniel Currier, 1847.

Image Credit: From the Library of Congress via Wikimedia Commons, public domain

Other Releases in the Whiteboard series:

- THE ADMINISTRATION’S TOP FOREIGN POLICY PRIORITY (A WHITEBOARD)

- AFTER 2020, WHAT’S NEXT? (A WHITEBOARD)

- IMAGINING OVERMATCH: CRITICAL DOMAINS IN THE NEXT WAR (A WHITEBOARD)

- THAT ONE MOST IMPORTANT THING: (A WHITEBOARD)

- SHALL WE PLAY A GAME?

(WARGAMING ROOM) - WAR(GAMING) WHAT IS IT GOOD FOR? (A WHITEBOARD)

- LEADERSHIP ROLE MODELS IN FICTION REVISITED: (A WHITEBOARD)

- WHAT GOOD IS GRAND STRATEGY? (A WHITEBOARD)

- THE UNITED NATIONS’ GREATEST ACCOMPLISHMENT: (A WHITEBOARD)

- LEADERSHIP ROLE MODELS IN FICTION: (A WHITEBOARD)