If we’re all being honest, what we’ve really missed while not traveling is the joy of capturing our adventures in the conveniently-automated Defense Travel System (DTS) upon our returns.

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has affected the Department of Defense in all manner of ways, but with Permanent Change of Station (what the military calls ‘moving’) season upon us, travel restrictions have moved to the forefront. With some notable exceptions, including an acting service secretary flying halfway around the world to address sick sailors and then flying back to Washington only to decide he had chosen his words poorly, most travel has been dramatically curtailed.

With new jobs ahead, many service members are once again looking forward to thirteen-hour flights to the Middle East with recycled air, the best lounges smart majors can sneak you into, and attempts to look inconspicuous—OPSEC, it’s everyone’s responsibility—but upon landing and visiting the Star Wars cantina-like airport bar, a young soldier walks up and says, “Follow me, the van is this way.” If we’re all being honest, what we’ve really missed while not traveling is the joy of capturing our adventures in the conveniently-automated Defense Travel System (DTS) upon our returns. Uncle Sam has little trouble cranking out travel orders, but he is more reserved when it comes to opening his wallet to cover the costs incurred buying things like, say, airline tickets. Save those receipts!

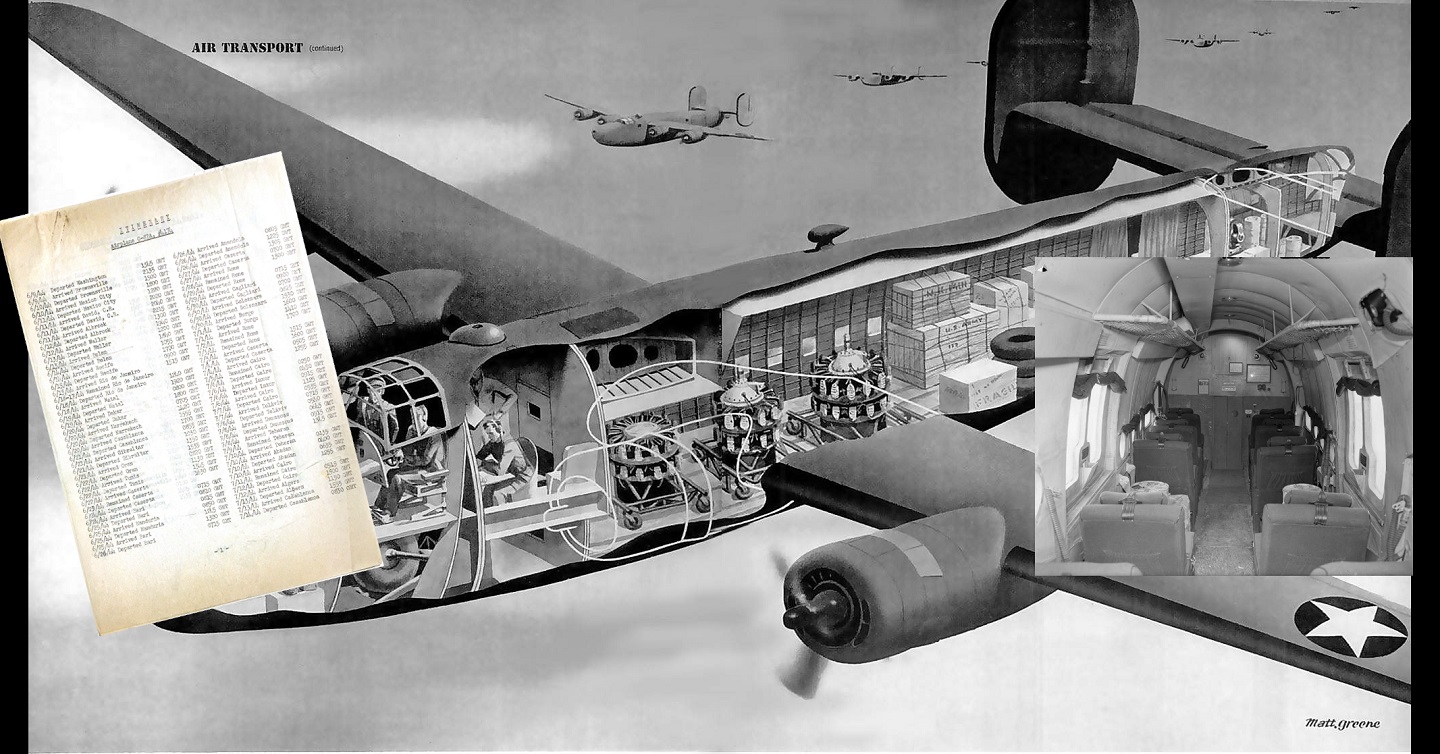

The following document, pulled from the Military History Institute housed at the U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center, offers hope, dread, or inspiration depending on one’s ultimate station in the Defense Department. Hope, for those destined to become combatant commanders one day. Business jets will be faster and cooler than the C-87 Liberator Express, a modified B-24 Liberator bomber, used for the trip described in the link below. With a modern communications suite, future combatant commanders need not worry about mail forwarding as described in the document. Dread, for the colonels working directly for the general officer planning such a trip. This of course involves a whole lot of briefing books to wrangle out of the staff before the flight to Mexico. And, for the current military students in advanced education programs out there, inspiration, knowing you will never be the poor major attempting to process such a claim at the back end of this jaunt. With the skills acquired at Leavenworth, Maxwell, Newport, Norfolk, Quantico, or Carlisle, you would craft a better plan.

One thing from this document emerges clearly. Winning World War II would have been impossible with DTS. Thank goodness for a simpler time of carbon paper, pencil corrections, clerk typists, and a global war to be won. On the other side of the ledger, be grateful for accomplishing in one (very long) day of travel hassles what might have taken a week and two extra continents of connecting flights to accomplish in the 1940s.

The document under review is Major General Guy V. Henry, Jr.’s itinerary of travel to South America, Africa, Europe, and the Levant during the summer of 1944. One can only imagine trying to work out the details of such a trip in DTS today. A brief description of MG Henry’s amazing career follows the link to his big trip, one of many flights he conducted during the war in pursuit of hemispheric defense with the United States’ Canadian and Mexican strategic partners.

All travel humor aside, General Henry offers a remarkable example of a life dedicated to the service of his nation; he is also someone about whom very few people know anything. The son of Guy V. Henry, Sr., a remarkable figure in his own right—USMA 1861, recipient of the Medal of Honor for actions during the Civil War, service during the Indian campaigns, and military governor of Puerto Rico—the younger Henry was born in an Army tent in Nebraska as the temperature outside registered around -40 degrees Fahrenheit. After graduating from West Point in 1898, Lieutenant Henry catapulted to Major Henry, U.S. Volunteers in 1899 during the Spanish-American War where he saw combat in the Philippines and earned the Silver Star. After a stint as a military aide to President Theodore Roosevelt and attendance at the French Cavalry School, Henry revitalized and transformed training and education as it related to the cavalry’s equestrian pursuits—Henry taught the 20th century Army how to ride. He also represented the United States at the 1912 Olympics in Stockholm, the same games that made Jim Thorpe a household name. Henry won a bronze medal in the equestrian team event competition along with teammate and future general, Ben Lear. Throughout the rest of his life, in and out of uniform, Henry would exert a guiding hand on American Olympic equestrian efforts while witnessing its transition from being an Army responsibility to a civilian pursuit after the elimination of horse cavalry.

Henry was the Commandant of Cadets at West Point, served on General John J. Pershing’s staff during World War I, and transformed the cavalry again as Chief of Cavalry, 1930-1934, with the inception of the 7th Cavalry Brigade, Mechanized, which he then commanded. Henry commanded the Cavalry School during what he thought would be his last assignment. After retiring in 1939, the Army recalled him to active duty in 1942 to serve as a member of the U.S. delegation to the Permanent Joint Defense Board with Canada. Retiring a second time in 1947, Henry put on his uniform again in 1948 as the Chairman of the same board until 1954.

Guy V. Henry, Jr., died in 1967 after a long, full, and distinguished life. But perhaps no time in his 92 years was quite so busy as that trip in the summer of 1944, which makes moving this summer, even in the era of COVID-19, seem easy.

Major General Henry’s travel itinerary

Colonel Matthew Morton is the Director of Army Planning in the Department of Military Strategy, Planning and Operations at the U.S. Army War College.The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

Photo Description: The Consolidated C-87 Liberator Express was a transport derivative of the B-24 Liberator heavy bomber built during World War II for the United States Army Air Forces. A total of 287 C-87s were built alongside the B-24 at the Consolidated Aircraft plant in Fort Worth, Texas. (Wikipedia)

Photo Credit: Original illustration by Matt Greene/Composite by Haberichter