Yet for all the insights it has unearthed, this diverse scholarship does not get to the bottom of a foundational question: why do democracies win wars?

Historians long have considered the various facets of armed conflict in western history, from the linkage of warfare to agriculture in ancient Greece, to the military revolutions of seventeenth-century Europe. Some have considered how the rise of modern fiscal-military states, especially Great Britain, enabled wars for empire. In the United States, scholars have identified and disputed an American “Way of War” that seeks the overthrow of adversaries by annihilation. Others have established that Americans were uniquely competent in raising large volunteer armies and projecting military power across continental distances, and they have noted that dominance in industrial power positioned the United States for global hegemony. Yet for all the insights it has unearthed, this diverse scholarship does not get to the bottom of a foundational question: why do democracies win wars?

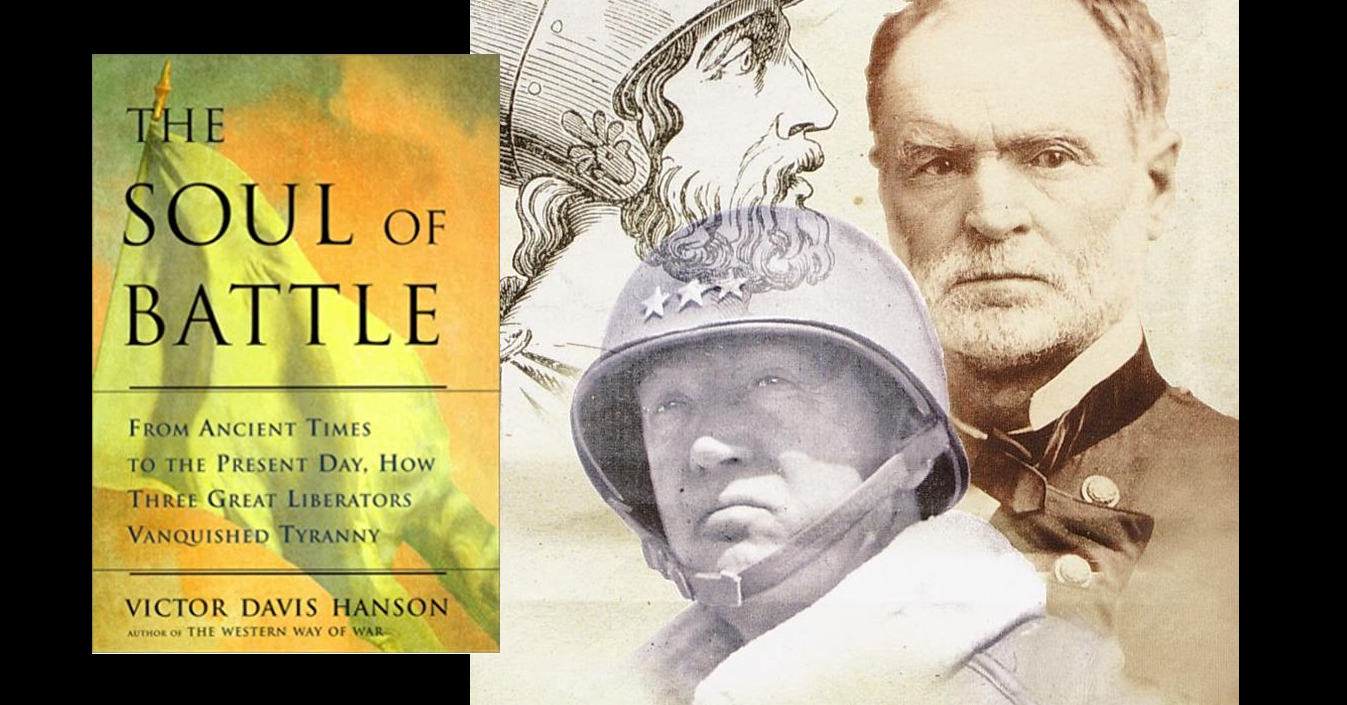

To this question classicist Victor Davis Hanson offers an answer in The Soul of Battle: From Ancient Times to the Present Day, How Three Great Liberators Vanquished Tyranny, an insightful and less controversial work than some of his other military histories (such as Carnage and Culture). The Soul of Battle examines “the ethical nature of democracies at war” and posits an ageless spirit in warfare waged by free peoples (13). According to Hanson, democratic societies are distinctive because they “produce the most murderous armies from the most unlikely of men,” and because such armies fight “in the pursuit of something spiritual rather than the mere material” (5). In wars ancient and modern, democratic armies have had commanders possessed of eccentricity, erudition, a sense of fatalism, and radical moral fervor. These armies, capable of rapid musters and of making inroads into an enemy’s heartland, conquering, and then disbanding, have vanquished evil on vast scales not because of superior numbers or materiel, but because they believed themselves to be more moral than their enemies.

Hanson analyzes three commanders and their armies of citizen-soldiers who sustained extensive marches deep into the interior of enemy-held territory, where the very presence of liberating armies made manifest the contrasts between free and unfree peoples: Epaminondas of Thebes, who united farmers from the Boeotian plain and marched across the Spartan Peloponnese in the fourth century B.C.; William T. Sherman, who gutted southern agriculture and infrastructure by leading his army across Georgia in 1864; and George S. Patton, whose army advanced across Europe to help destroy the Nazi slave state. All three captains possessed supreme talent in war but were ill suited for peacetime. Remembered as brutal warriors, all three were in fact great moralists whose destruction flowed from an innate humanitarianism. Their marches of liberation are distinctive from the campaigns of such captains as Alexander the Great and Napoleon, whose victories advanced autocracy and empire.

Princeps Graeciae

It is commonplace to trace western democratic republicanism to Athens, the most cosmopolitan of the Hellenic poleis. A more egalitarian democracy to emerge from the classical Greek world arose first in Thebes and the fertile farm country of Boeotia. In the fourth century B.C., Boeotian factions united to create a classless democratic federation that defeated a Spartan garrison and eliminated pro-Spartan Thebans, and thus acquired democracy.

In the van of this revolution stood Epaminondas, a Theban of noble descent and average means, student of Pythagoras, lover of democracy, astute warrior, and “incorrigible Spartaphobe” (53). To destroy Sparta’s military might, Epaminondas needed to liberate thousands of Messenian Heilόtai who cultivated Spartan agriculture. Helotage was not slavery in the legal sense, but it was oppressive and savage, akin to the institutionalized racial slavery later found in the Atlantic World. Helots enjoyed no legal protections; Spartans murdered them in secret, and ritualistic beatings of helots headlined Spartan festivals. In short, Spartan helotage embarrassed and threatened Greeks who idealized autonomous democratic city-states. Epaminondas knew that liberating Laconia and Messenia—thereby severing Spartans from their food supply—would bring Sparta to its knees.

In the winter of 370 B.C., Epaminondas crossed the Corinthian isthmus with an army of 20,000 men and headed for Laconia and Messenia to end the Spartan menace and free helots. At Mantinea Epaminondas acquired additional troops, swelling his ranks to 70,000 (79). Epaminondas’s columns descended upon the Laconian plain and crossed the Eurotas River. Terror swept the Spartan polis. Women—property owners under Spartan law—witnessed the destruction of the surrounding countryside. Spartan women were “a wealthy class famous for bravado” and urging their sons and husbands to kill (90). But no Spartan hoplite left the city to confront Epaminondas. Even the Spartan king disappeared among the city’s labyrinthine streets in retreat. Epaminondas spared the polis but burned the Spartan seaport. Then he erected a democratic and fortified city at Messene. Displaced Messenians and former helots from the far corners of the Mediterranean world flocked to Epaminondas’s army and freedom.

The Devil in Georgia

Like Epaminondas before him, William Sherman possessed uncommon insight into the moral-ethical dimensions of warfighting and the forces that motivated an enemy citizenry. Better the destruction of his enemy’s property and the confiscation of enemy food stores—even the expulsion of southern families from their homes—than the bloodletting that would result from confrontations between armies. To Sherman, a perverse immorality permeated southern thinking (138). Southerners willingly sacrificed human beings in their irrational and hateful insurrection but expressed outrage from beneath a chivalrous veneer when northerners targeted their property.

Sherman’s march across Georgia in 1864 enabled Federal volunteers (many of whom were fiercely independent farmers from western states) to see slaves for the first time, engendering sympathy in the rank and file. The march also occasioned verbal exchanges between northern troops and members of the southern plantation class. Westerners who endured insults from southern women, and who suffered lectures on the march from “strong-minded” locals about “black Republican” rule (and the inevitable “horror” that would attend the amalgamation of races), laid bare the sinister and abusive nature of slavery. Sherman’s troops inquired with plantation mistresses about how it was, if racial amalgamation was truly to be abhorred, that slaves who roamed southern estates “came to be so much whiter than African Slaves [were] usually supposed to be” (197).

Most important of all, Sherman’s columns destroyed racial slavery. Federal naval vessels could not free enslaved persons from coastlines and waterways. Noble though it was, the Emancipation Proclamation was powerless to liberate persons it freed in letter. Sherman’s army accomplished this, singing the “Battle Hymn of the Republic” and “John Brown’s Body” as it marched. Sherman—who had no sympathy for abolitionism, who harbored unfavorable views of African Americans and Native Americans, and who was distrustful of democracy—nevertheless did more for the direct liberation of many thousands than all the social activism in the North that animated emancipation.

In truth, Patton’s coarseness paired well with his erudition and practical experience.

Old Blood and Guts

General George Patton, like Sherman and Epaminondas before him, had a “studied eccentricity and unrepentant moral fervor” that earned the respect of his men and the fear of his enemies (269). Hanson regards Patton as an anachronistic figure, one “who belonged more to the nineteenth century” than to the modernizing world of the twentieth century (270). Intelligent and educated, Patton spoke with great candor about his enemies on and off the battlefield, giving the false impression to many that the general was unstable.

In truth, Patton’s coarseness paired well with his erudition and practical experience. He kept extensive reading lists and a voluminous library (274). He devoured classics of political history, military theory, and campaign histories of non-European wars. In Normandy, he studied the campaigns of William the Conqueror and Julius Caesar (274). Patton was conversant with a wide range of biography and with the commentaries of Caesar, Alexander the Great, and Scipio Africanus; he possessed, probably alone of all Allied commanders, extensive knowledge of Epaminondas’s march across the Peloponnese (275). Mobile warfare was his specialty: “every element of the Third Army’s operation in Normandy—tanks, infantry, rifles, machine guns, intelligence, methods of maneuver—[Patton] had either read widely on or himself written about” (275; original emphasis). Experience, too, was Patton’s school. He worked his way through the U.S. Army, familiarizing himself with operations and staff functions from company to division, and acquired armored combat command experience in World War I. Patton was one of the principal founders of American armored forces and doctrine.

His campaigns of 1944-45 earned the American field army commander his greatest acclaim in the Allied popular imagination and terrorized his enemies. Like Epaminondas and Sherman, Patton excelled in the indirect approach punctuated by speed and maneuver. At almost 500,000 men and fighting along fronts as extensive as 100 miles in length, Patton’s Third Army inflicted ten times as many casualties on the Germans as it suffered and liberated some 81,500 square miles of European territory (303). In nine months of operations, Third Army captured one million Germans at a clip of 2,724 enemy soldiers per day (303). Third Army could, and did, “kill devastatingly”—the purpose of any army in war, as Patton declared on Memorial Day, 1943—but Hanson contends that the rapid thrusts with which Patton preferred to cut off his enemies from retreat enabled his GIs to take many thousands of Germans alive whom they otherwise would have annihilated. And in all of this, Third Army liberated untold numbers of French citizens and thousands of Jews, Gypsies, Slavs, and non-Aryan Europeans from concentration camps, persons the Nazis regarded as irredeemable and subhuman, and whom the Germans had systematically slaughtered with the most advanced industry and technology then known to humankind.

Dust off the shelf

Hanson’s prose is robust, and his analysis of military campaigns compelling. And yet The Soul of Battle offers more than skillful operational history; it furnishes deep insight into human nature and the character of war itself. Indeed, armed conflict is a fixture of human nature, and there is a spiritual essence of warfighting that is inscrutable to pure scientific reasoning. In wars that involve human personality (all wars), “there finally must be a choice between good and evil” (412). Contemporary military practitioners should remember, as did Epaminondas, Sherman, and Patton, that “the real immorality” in armed conflict is “not the use of great force to inflict punishment,” but rather the refusal “to exercise moral authority at all” (412).

Hanson’s examination of how Patton succeeded in inspiring Third Army to defeat Nazi Germany is useful for all concerned with soldierly motivations. Unlike their more idealistic and politically-minded forefathers in the Civil War, GIs in 1944 viewed war not as a grand moral crusade, but rather as a disruption of comfortable living. Most were suspect of, and even hostile to, the idea of moral motivation in war. The exigencies of military service in Europe were thus analogous to simple labor, and the defeat of Nazi Germany another task to be accomplished. The industrial scale and global scope of the Second World War reinforced this sense. How, then, did Patton motivate his GIs? Even without clear knowledge of the Holocaust, Patton rightly believed the Nazis to be ruthless murderers and said so openly. He imbued his troops with a sense of moral superiority and with an ideological hatred of their foe (sometimes to excess). He underscored the necessity of efficient killing, kept his army supplied, tapped into the passions and adolescent recklessness of his troops, and set them loose on a mechanized tear across Europe that crippled the Nazi slave state and liberated thousands.

Hanson’s politics are contentious and his historical conclusions sometimes overwrought, facts that have caused many to dismiss his scholarship whole cloth. Nevertheless, the thesis of The Soul of Battle merits careful re-examination. “The great danger of our present age,” Hanson warned when his bookfirst appeared, “is that democracy may never again marshal the will to march against and ultimately destroy evil” (412). Four years later, the United States and her coalition partners defeated Iraq’s Ba’ath regime. Millions of Iraqis were made free and instituted representative government. Interpreted in this light, the deliverance of Iraq answered Hanson’s warning. While irregular warfighting and political destabilization in Iraq after the American intervention offers a cautionary tale, the initial success of American arms and the swift campaign that liberated Baghdad supports, if not validates, Hanson’s thesis, and demonstrates anew how democratic armies can unleash destructive power when directed toward humane ends.

Mitchell G. Klingenberg, PhD, is a military historian in the Department of Military Strategy, Planning, and Operations at the U.S. Army War College. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

Photo Description: 1st and 2nd Edition covers of The Soul of Battle: From Ancient Times to the Present Day, How Three Great Liberators Vanquished Tyranny