On October 20, 1962, with the Missile Crisis already underway, the base commander’s staff was informed of the possibility for a short-notice evacuation of the installation’s dependents.

In the fall of 1962, the United States and the Soviet Union came as close as they ever would to global nuclear war. Plenty of sources document the details on the diplomacy and statecraft involved in settling the Cuban Missile Crisis, and the massive joint force assembled near Cuban waters to “quarantine” incoming arms shipments. Often overlooked in that story is the only American military presence in Cuba, the Navy installation at Guantanamo Bay. It served as primary in-theater warfighting platform and broadest, slowest target if shooting began. In addition to military personnel, it housed nearly 3000 non-combatant dependents whose only way off base was by air or sea (access to the rest of Cuba had stopped in 1959 after elements of the Castro regime had kidnapped a liberty bus of Sailors and Marines). The mimeographed page which instructed dependents on how to leave is an elegantly simple document which helps tell the story of how the United States managed to continue its presence, secure its population, and enable national objectives.

On October 20, 1962, with the Missile Crisis already underway, the base commander’s staff was informed of the possibility for a short-notice evacuation of the installation’s dependents. The next day, the Joint Chiefs of Staff directed the Commander in Chief, Atlantic to prepare to evacuate dependents from Guantanamo and to reinforce the base. The base’s assistant chief of staff for administration was assigned the task of preparing for a secret evacuation procedure, which he named “Operation Quicklift.” (There is no evidence that that name was ever made official, and “Quicklift” has made it into other named operations.) Soon after, base commander Rear Admiral Jerry O’Donnell received the execution order directing all dependents depart by sea or air before 5:00 PM, October 22. The Secretary of Defense issued that order as a result of the possibility that Cuban, Soviet, and other Communist Bloc forces on the island could attack the base or use the safety of its inhabitants as a bargaining tool against the United States.

A crisis-contemporary report from one of Guantanamo’s on-scene evacuation planners, Lieutenant Junior Grade H.W. Sawyer, wrote of his role during the evacuation. “… notified [of the order] at 1000 on October 22…provided with mimeographed instructions for the dependents; a brief, secret notice to be read to the wives, which informed them that this was not a drill; a small booklet to record any ‘not at home’ addresses; and a black grease pencil to mark all evacuation quarters [with a “V” for vacated]….In less than two hours, every dependent woman and child had been evacuated to the staging area.”

The message read in part “URGENT. Higher authority has directed the immediate evacuation of all dependents from the Naval Base….pick up your pre-packed suitcases (not more than one per person)…. DO NOT PROCEED BY CAR…. Tie up pets in the yard. YOU MAY NOT TAKE PETS WITH YOU. Leave house keys on the table in the living room. PUT THIS IN YOUR PURSE.” It was delivered throughout the base’s family housing by senior enlisted and junior officers. (After evacuation, Sailors would be assigned to care for the pets left behind.)

Seven years later, O’Donnell would describe more about the distribution process in a letter responding to a student’s query. “Another important aspect of the immediate planning was the distribution of the handbills… The system worked very well indeed and in a similar situation, even if it were not necessary to cover the evacuation, I believe that the written handbill, personally delivered by an officer, tends to minimize excitement and emotional reaction, as contrasted to getting the information by radio or T.V.”

Many of the evacuees, primarily wives and children, left with clothes in their washing machines and food cooking on their stoves. Because of limited available news on base, some were unaware of the current tensions with Cuba until they received the evacuation orders. “All we had was the base newspaper,” said one student at the base’s high school.

In less than five hours, 2,700 civilians were pulled from their daily routine, informed of their departure, and sent toward the American mainland.

According to in an unpublished report Sawyer wrote about the event, “Personal observations regarding the evacuation of GTMO dependents,” the first group left on an aircraft “which had arrived only shortly before laden with urgently needed arms and equipment.” Most of the evacuees left on four ships, the majority on USNS Upshur, bound for the Hampton Roads, Virginia area. The last ship carrying evacuees got under way by 4:30 p.m. In less than five hours, 2,700 civilians were pulled from their daily routine, informed of their departure, and sent toward the American mainland. President Kennedy noted the operation in the speech he gave that night which announced the establishment of a naval “quarantine,” and mentioned the evacuation of dependents from Guantanamo Bay as one of the steps he had taken. He also waited until those dependents were beyond the quarantine’s boundaries to make that announcement.

Soviet Union leadership decided on October 26 to withdraw the missiles, even as the Castro regime called up militia reserves and prepared for a U.S. invasion which they expected to come from the base. The dependent evacuation was a footnote to the greater Navy efforts: America’s ships and statecraft receive the most study and credit for its successful conclusion, and in more recent years, more information about behind-the-scenes diplomatic machinations has been made public. But historian Stephen Irving Max Schwab says of the base’s role in the Crisis: “Guantanamo was, if not central, an important aspect of this tension-filled period. The outcome of the crisis was to reinforce U.S. determination to retain the base. [Realizing] it had won a significant victory in both diplomatic and military terms over the Soviet Union and Cuba, the JFK administration was in no mood to make any concessions regarding the U.S. presence at Guantanamo.”

The evacuation memo would not, without context, match the gravitas or inspirational quality of General Eisenhower’s succinct message to those about to embark on the “Great Crusade” of Operation Overlord or similar orders and speeches. Operation Quicklift involved far fewer personnel and platforms than did Overlord and did not precede the liberation of an entire continent. But the Cuban Missile Crisis is now frequently cited as the closest the United States and Soviet Union came to nuclear-conflict—the greatest calamity in human history that never happened. And Guantanamo could very well have been where the opening shots began.

A forward base like Guantanamo Bay is persistent and operational in large part because of its non-military inhabitants. Dependents and other, strictly speaking non-operational personnel, allow for sustained presence, but may at times restrict options and agility. The order to evacuate those dependents, not just off the base but outside of the soon-to-be-implemented naval “quarantine” limits, allowed for increased agility and more diverse options. In addition to facilitating the implementation of the quarantine and freeing up mental and physical resources of the base, the departing dependents were replaced by additional Marines. The quarantine was only politically viable (not putting innocent women and children in undue risk) once these dependents were out of the immediate area of operations. Their absence placed the enemy, the Soviets more than the Cubans, at a disadvantage.

Most of the dependents who evacuated returned early in December. The base would evacuate dependents again during the mass migration operation of the mid-90s, Sea Signal, which freed up limited space and resources for thousands of Haitian and Cuban migrants, and in anticipation of a hurricane in 2016. Dependent evacuations have been directed from other countries both for their own safety and to allow more resources for ongoing or anticipated operations, such as after the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami of 2011. Those more recent evacuations would, in contrast to Quicklift, not mention “purses” in their orders (dependents of course now include plenty of adult males), and would allow evacuees to take pets. These other operations would, however, not be as urgent or consequential as that carried out via the hastily composed memo from October 22, 1962. As O’ Donnell wrote in 1969, “Looking back on the situation, I think that the drawing up of the handbill, the language used, and the method of dissemination was one of the master strokes in the very great success of the operation.”

J. Overton is the editor of Seapower by Other Means: Naval Contributions to National Objectives Beyond Sea Control, Power Projection, and Traditional Service Missions, and a former Non-Resident Fellow with the Modern War Institute at West Point.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Naval War College and Marine Corps Command and Staff College, the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, the U.S. Coast Guard or the Department of Defense.

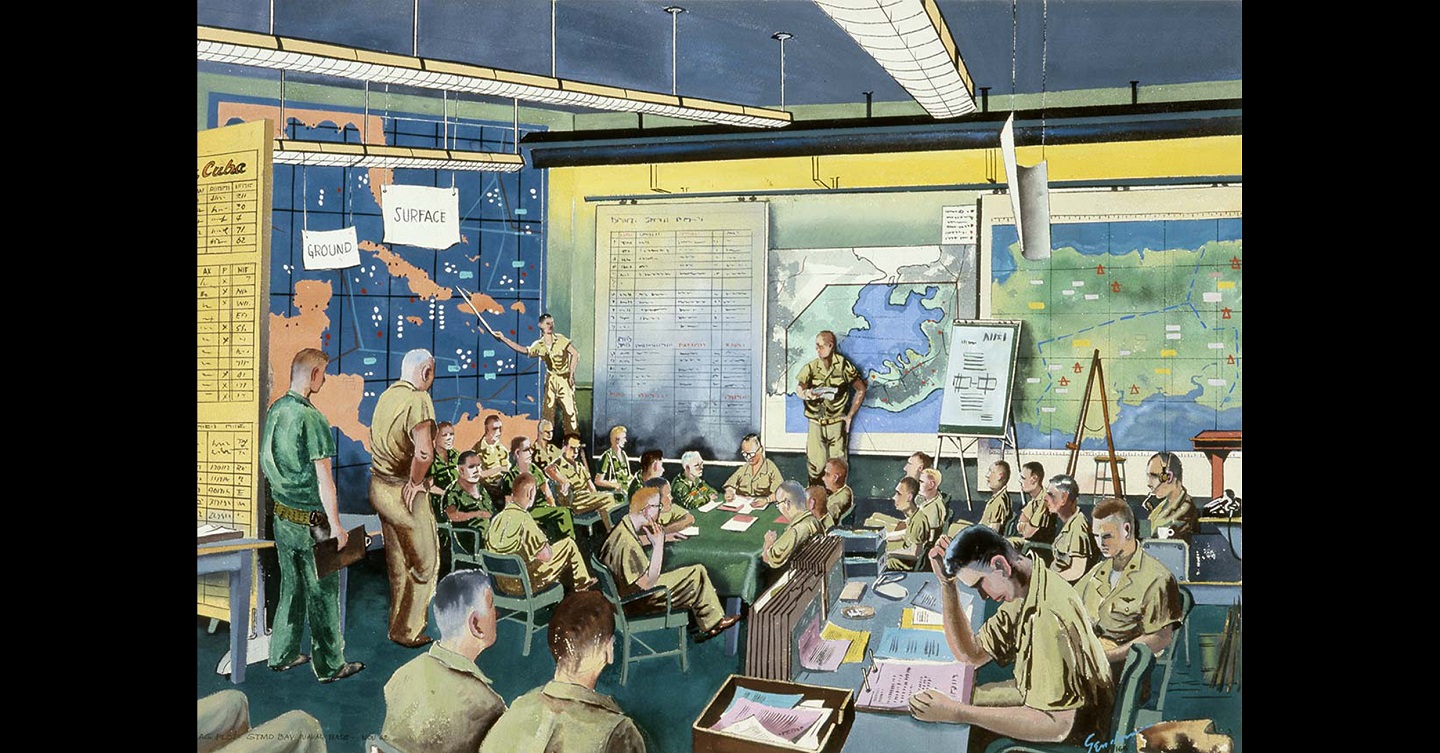

Photo Description: In the fall of 1962, the Soviet Union began construction on ballistic missile launch sites in Cuba. The United States responded with a naval blockade. For thirteen days, the fear of impending nuclear war continued until an agreement was reached for the removal of the weapons.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of the Naval History and Heritage Command, Watercolor on Paper; by Richard Genders; 1962

Other releases in the “Dusty Shelves” series:

- THE ARMED FORCES OFFICER (1988): THE FORGOTTEN PRIMER ON LEADERSHIP

(DUSTY SHELVES) - RIDGWAY’S KOREAN WAR

(DUSTY SHELVES) - ALL WAR IS LOCAL: ANTHONY QUAYLE’S EIGHT HOURS FROM ENGLAND

- POST-WAR TRUTH TELLING: THE WAR MANAGERS

- DYE: EXALTING THE TAIL OF THE AIRPOWER TOOTH

(DUSTY SHELVES) - PEACE FORMS: LOOKING BACK TO THE FUTURE OF WAR AND ANTI-WAR

- SHERMAN: THE OUTLIER OF INTERWAR “ATLANTIC” AIR THEORY?

(DUSTY SHELVES) - STRUGGLING TO SEE THE FUTURE: UNLESS PEACE COMES

(DUSTY SHELVES) - “ALL INVADED PEOPLE WANT TO RESIST”: STEINBECK’S THE MOON IS DOWN

(DUSTY SHELVES) - RACE TO THE SWIFT: APPLICATIONS IN 21st CENTURY WARFARE

(DUSTY SHELVES)