Remembering the past is hard, not just because memories fade but because capturing the past in a meaningful, relevant, and intellectually honest way is difficult, complex, and too often unrewarded.

LISTEN TO THE INAUGURAL EPISODE ON RIDGWAY’S 1951 MEMO HERE.

The great philosopher and writer George Santayana famously said, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” But, remembering the past is hard, not just because memories fade but because capturing the past in a meaningful, relevant, and intellectually honest way is difficult, complex, and too often unrewarded. This despite the fact that the Army’s professional ethos encourages the passing on of lessons learned.

Preserving the past serves a developmental need. All US military services devote extensive time and energy ensuring the lessons of wars past are passed onto current and future generations of service members. Staff rides and reading lists are two of the most common undertakings to ensure historical understanding and empathy while spurring professional development. Junior officers and noncommissioned officers pore over old maps, walk battlefields, and try to get into the minds and hearts of those who faced enemies and prevailed (or lost). Reading lists tout biographies of great leaders and thrilling campaign narratives as often as they do more academic or analytical works. Historical works help young men and women become more committed to their military and service identities as they think about how to fight, reflect on their own personal resilience, or consider the meaning of their service.

It also represents an institutional need. Time is an enemy of memory. Teenagers who graduated high school in 2017 have no first-hand memories of the events of 9/11, even as some of them will go on to serve in wars that began in its wake. Much less do they have memories of the Vietnam War or World War II—and the number of veterans of those wars and those with personal experience diminishes daily. Wars fought before the twentieth century are distant memories that exist only on paper and perhaps in old photographs. Leading the defense enterprise into the future involves carrying forward history’s lessons, but recent events gain salience. The memories that are most readily available come to the forefront of analysis and comparison. It is easy right now to view the US military through the lenses of Iraq and Afghanistan and to become blind to the myriad other historical experiences that might inform strategy and policy. Rigorous and careful historical work can help guard against this tendency.

Historical memory and learning serves personal needs as well. Samuel Hynes in The Soldiers Tale argues that war writing—poetry, fiction, journals, prose, history, letters—serves two functions: the need to report and the need to remember. The digital 21st century has expanded exponentially the voices and experiences of those who have served in Iraq and Afghanistan. Those experiences and the stories of bravery, courage, and tragedy are fresh, relevant, and currently plentiful. Similarly, the victorious fighting forces from World War II returned with stories that service members told to their children, and then grandchildren. Each returning cohort—across time and space—has done the same. Historical thinking and understanding then helps interpret and contextualize these voices.

The podcasts and articles in this series will present historical artifacts, tell their stories, and relate the lessons learned to the modern environment.

Finally, historical thinking serves societal needs as well. In addition to writing about war and the military, movies and other visual representations of war and military life often serve this social need. For example, consider the impact of Patton or Saving Private Ryan on the American narrative and memory of the Second World War, or of Rambo and Apocalypse Now on the memory and interpretation of the Vietnam War. Movies and art have helped keep some memories alive among the US public, although more in feeling than in fact. The nexus between popular historical imagination and rigorous academic analysis is often quite small.

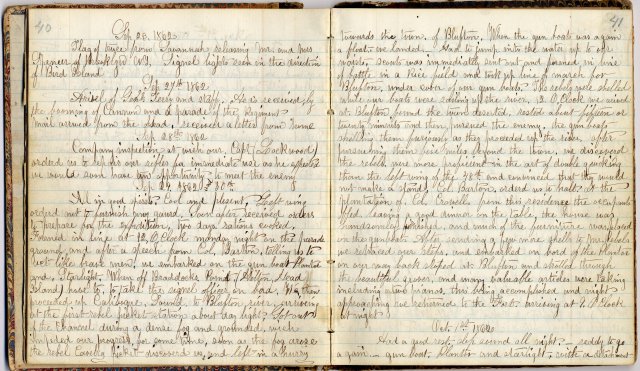

Of present importance is how much the US military has relied on the written word and tangible artifacts to remember its history. Diaries, personal letters, official documents, keepsakes, war trophies, mission logs, maps and graphics—all have been used to preserve both the facts of what happened ‘on the ground’ and the ideas and feelings running through the minds of strategic leaders and individual warriors alike. We know much about Ike Eisenhower from his actions both as warfighting commander and as President, but much much more because of his extensive reflective writings.

But for every one Eisenhower, there are thousands of other artifacts—writings and objects—sitting on dusty shelves in libraries, museums, repositories, or trunks in attics. Some of them reinforce well-known and traveled stories, but others have unique tales to tell on their own. In an ever-evolving strategic environment, some of these older tales may now be very relevant.

‘Dusty Shelves’ is a new recurring series in War Room that focuses on such artifacts and their stories. The podcasts and articles in this series will present historical artifacts, tell their stories, and relate the lessons learned to the modern environment. It will serve as a springboard for the US military to better remember parts of its past that it most risks forgetting. Dusty Shelves is presented in collaboration with the Army Heritage and Education Center, located at Carlisle Barracks. This grand facility is home to hundreds of thousands of individual artifacts of Army history, serviced by a dedicated team of historians whose mission is to preserve the full story of the Army. The first episode discusses a letter penned by General Matthew B. Ridgway’s memorandum of January 21, 1951 upon taking command of a broken and dispirited Eighth Army in Korea after its retreat.

We hope you enjoy the series, and welcome comments and suggestions for future episodes.

Photo: Pages from Corporal William Howard’s 1861-1863 diary describing a December 1862 amphibious attack on the town of Blufton, South Carolina.

Photo Credit: New York State Military Museum

Posts in the “Dusty Shelves” series:

- THE ARMED FORCES OFFICER (1988): THE FORGOTTEN PRIMER ON LEADERSHIP

(DUSTY SHELVES) - RIDGWAY’S KOREAN WAR

(DUSTY SHELVES) - ALL WAR IS LOCAL: ANTHONY QUAYLE’S EIGHT HOURS FROM ENGLAND

- POST-WAR TRUTH TELLING: THE WAR MANAGERS

- DYE: EXALTING THE TAIL OF THE AIRPOWER TOOTH

(DUSTY SHELVES) - PEACE FORMS: LOOKING BACK TO THE FUTURE OF WAR AND ANTI-WAR

- SHERMAN: THE OUTLIER OF INTERWAR “ATLANTIC” AIR THEORY?

(DUSTY SHELVES) - STRUGGLING TO SEE THE FUTURE: UNLESS PEACE COMES

(DUSTY SHELVES) - “ALL INVADED PEOPLE WANT TO RESIST”: STEINBECK’S THE MOON IS DOWN

(DUSTY SHELVES) - RACE TO THE SWIFT: APPLICATIONS IN 21st CENTURY WARFARE

(DUSTY SHELVES)