The circumstances for both exercises centered on an imagined invasion and occupation of Oahu, including the naval base at Pearl Harbor and surrounding Army airfields, by an enemy coalition dubbed “Black” forces.

In February 1932, the Army and Navy conducted concurrent training exercises, Grand Joint Exercise No. 4 and Fleet Problem XIII, respectively. These exercises, conducted during the Great Depression, proved valuable by exposing operational gaps rather than necessarily demonstrating capabilities. Eight years later, on the verge of a global conflict, wartime funding and modernization helped to address these shortcomings. As the current force prepares for potential budget cuts and as regional threats grow, these two exercises illustrate the value of training with reduced resources and demonstrate how those lessons learned can influence the United States’ approach to future conflict.

The circumstances for both exercises centered on an imagined invasion and occupation of Oahu, including the naval base at Pearl Harbor and surrounding Army airfields, by an enemy coalition dubbed “Black” forces. Major General Briant H. Wells, commanding general of the Hawaiian Department led the Black forces. These units included 20,000 notional troops, represented by men of the 19th Infantry Regiment, artillery, and 45 ground-based aircraft.

U.S. forces, designated as “Blue,” included a naval fleet with two carriers—the USS Lexington and USS Saratoga—and a ground component, the Blue Army Expeditionary Force. Admiral Richard Leigh (commander, Battle Force) served as the overall operational commander, with Major General Malin Craig (IX Corps, future Army Chief of Staff and War College Commandant) directing ground forces. Rear Admiral Harry Yarnell directed the carrier group.

The Blue Army Expeditionary Force consisted of 40,000 invasion (640 actual) troops, represented by men from the 3rd Division’s 30th Infantry Regiment, a singular battery of 75mm field guns, and a USMC battalion. During pre-invasion training in San Francisco, Blue Army Soldiers clambered out of second story windows on rope ladders wearing full equipment to simulate descending from transport ships into landing craft. Elsewhere, Sailors and Marines conducted swimming tests for both men and the draught animals required to pull the rolling stock once ashore.

While the troops trained, officers and staffs gathered to work out the details of the operational plans. The concept of the operation contained three courses of action, each with separate landing areas. All required fighter support from the carrier group. The exercises focused on assessing joint expeditionary operations and testing Hawaiian defenses, although Navy officers viewed this as an opportunity to test aviation doctrine and strike capabilities. The aircraft were grouped by function on board the carriers. The Saratoga contained the majority of the fighters, while the Lexington housed scout and bomber aircraft.

The Blue force departed from the West Coast on January 31, 1932, with two transports carrying the invasion force. The ships rendezvoused with a Blue naval escort force including the flagship, the USS California, en route to Hawaii. By February 11, the invasion force arrived off Oahu, but Black submarine activity forced Admiral Leigh to divert from his preferred course of action—a landing on the northern beaches—to the third option. The Blue force prepared to sail to the west coast of Oahu to prepare for disembarking troops the next morning. Before the fleet departed, daring Black fighters streaked out of the night sky and dropped flares, simulating ordnance, on the transports. Umpires assessed that two notional troop transports sunk during the raid.

The sparse Blue air cover was the result of ongoing air and naval battles. Five days prior to the Black night attack, Admiral Harry Yarnell ordered the fighters from the Saratoga to launch at daybreak and attack key infrastructure locations at or near Pearl Harbor. Two waves of Blue fighters attacked the grounded enemy air force, with many of the pilots still asleep, and destroyed several key facilities. Once airborne, ground-based fighters and submarines depleted Blue’s air fleet and damaged the carriers. This action resulted in limited aerial support for the landings on February 12.

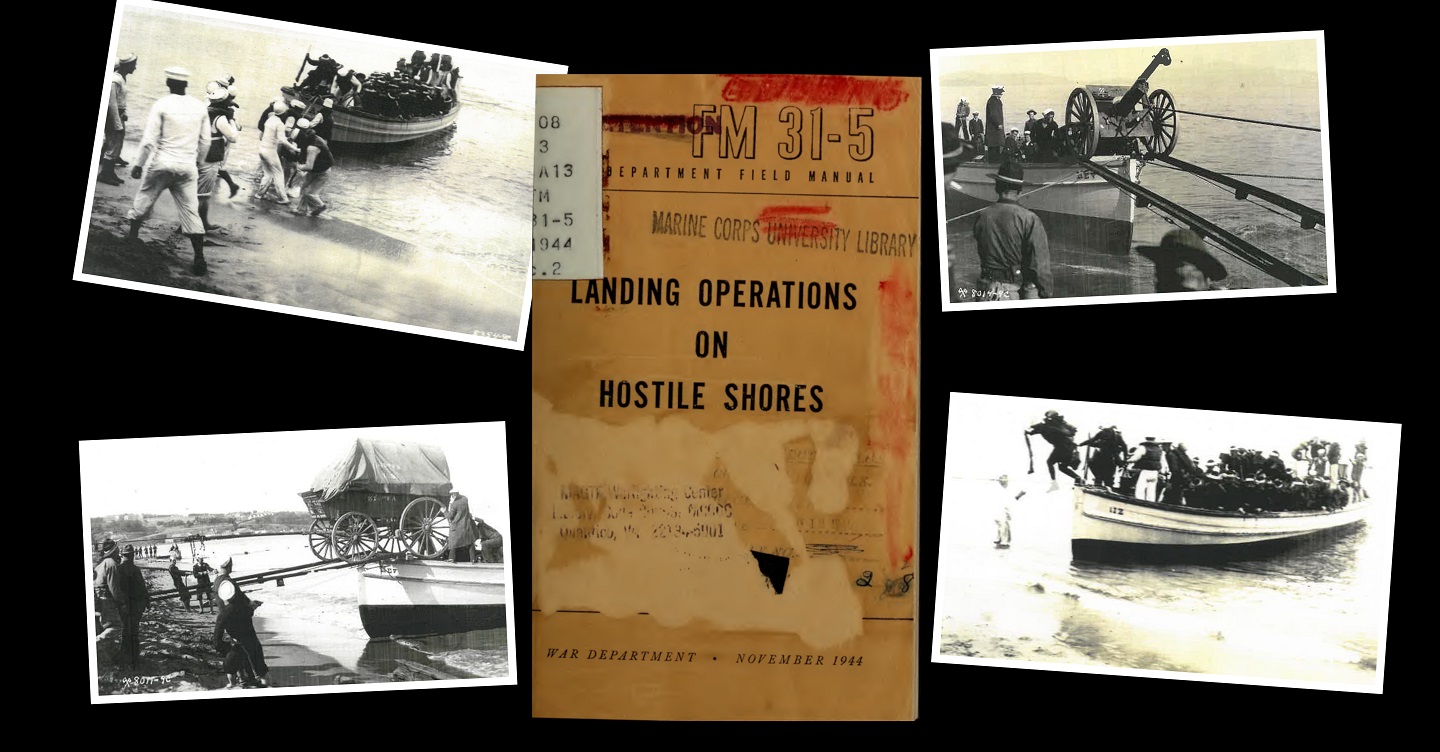

The technologies and techniques were antiquated, and the exercise occurred in an era of austerity for the War Department: the Army’s budget dropped from $9 billion in 1919 to $476 million more than a decade later. Troops splashed ashore carrying M1903 Springfield rifles and wearing World War I-era equipment. Landing craft were 40’ and 50’ motor launches borrowed from the Pacific Fleet, carrying the abbreviations of their parent ship, including ‘NEV’ (USS Nevada), ‘TENN’ (USS Tennessee), and ‘ARIZ’ (USS Arizona). Parties of Sailors standing ashore used heavy towropes to drag the boats onto the beach, minimizing the infantrymen’s exposure to the surf.

Landing rolling stock proved a more complex task. Fifty-foot launches, fitted with steel ‘I’ beams were used to carry the artillery, caissons, and wagons to the shore. The spoked wheel rims fit inside the beams and, upon beaching, the rails in the boat were elevated and connected to another set leading onto the beach. Using ropes and brute strength, shore teams pushed the rolling stock out of the launch and down the rails onto the beach, while other Sailors waited for the mules and horses to emerge from the surf.

Planners concluded that letting the animals swim ashore was safer and more efficient than attempting to place them in a launch, carry them to the beach, and offload them. Hinged ‘dumping’ stalls and a crane from a minesweeper with a sling attached were used to safely deposit animals in the water. Crews of Sailors in whaleboats used oars and poles to direct the mammals towards the shoreline.

Army troops landed at ‘L’ beach (Makua) and the Marine battalion secured ‘N’ beach (Waianae) seven miles to the south. The landings did not go unopposed, and Black fighters sunk a transport ship and strafed both beaches, “destroying” landing craft. Umpires assessed heavy casualties on the invasion force. Blue aircraft shifted between supporting the beach landings and attacking targets further inland.

Although the Soldiers, Sailors, and Marines participating in the exercise were exhausted, the lessons learned by both senior leaders provided a way forward in preparing for the next conflict.

As the infantry began their inland advance, the combat troops did so without artillery or supply wagons. The rolling stock and the animals that pulled the conveyances and guns took more than seven-and-a-half hours to land and would not be ready to move until 1430 . The Blue invasion forces marched southward towards their objective, Nanakuli. The wheeled column traveled seven miles before linking up with the advancing infantry. The 75mm guns were brought up and conducted preparatory fire on Nanakuli before the umpires called the end of the exercise at 1630.

Although the Soldiers, Sailors, and Marines participating in the exercise were exhausted, the lessons learned by both senior leaders provided a way forward in preparing for the next conflict. Fleet Problem XIII and Grand Joint Exercise No. 4 demonstrated both carrier-based strike capabilities and amphibious capabilities, while exposing vulnerabilities.

Admiral Yarnell’s daring raid against Black occupation forces on Oahu revealed gaps in Pearl Harbor’s defenses. Instead of rewarding the Blue attack, the umpires imposed heavy losses on the attacking force while minimizing damage to shore installations. The attacks also rendered the Saratoga and Lexington susceptible to enemy countermeasures, primarily from Black submarines and attack aircraft. Senior admirals reasoned that the next conflict would require expanded carrier and air fleets, along with the warships required to protect them.

The operation also provided critical lessons to Army leaders. Although the disembarking procedures went without incident, the limitations of unprotected motor launches—including pre-positioned shore parties with towropes—and the extended time it took to land rolling stock and animals exposed a fatal shortcoming. The next war required functionally-designed armored and armed landing craft to rapidly and efficiently move personnel and vehicles from ship to shore. General Craig noted that the antiquated wheeled guns and their animal transport used in the exercise should be replaced by artillery mounted on mechanized platforms to roll on and off landing craft, providing immediate fire support to the infantry establishing a beachhead.

Command problems during the exercise revealed the need for joint amphibious doctrine. The command channels for Marine ground units frustrated General Craig. USMC officers onshore received their orders from Navy superiors and not from General Craig’s staff. The future Chief of Staff of the Army recommended that Marine invasion forces—once ashore—should be directed by the senior Army commander and not by naval officers.

General Craig also expressed concerns about the limited close air support available during the landings. Black fighters flew above the beach head, strafing infantry stranded in the sand and destroying landing craft. Blue fighter support, depleted during the ongoing land and sea operations, provided limited support to the landings. General Craig concluded that operational success in amphibious operations required air superiority.

The Oahu exercises of February 1932 involved a number of influential Army, Marine, and Navy officers. As mentioned earlier, General Craig served as General George C. Marshall’s predecessor as Army Chief of Staff. Lieutenant Colonel Edwin P. Moses, commander of the (notional) Fifth Marine Brigade during the exercise attained the rank of Brigadier General by 1938 and served as the President of the Marine Corps Equipment Board. As President, he directed Donald Roebling to develop a variation of his civilian Alligator amphibian tractor using military specifications. This new design became known as the landing vehicle tracked, a staple of Marine landing operations during the Second World War. Major Keller E. Rockey, USMC, served as the Assistant Chief of Staff, G3, First Marine Division, Blue Army Expeditionary Force. Later, Lieutenant Colonel Rockey chaired a Marine Corps School board that revised and issued a new version of the Marine amphibious doctrine in 1937. In February 1945, he led the Fifth Marine Division during the invasion of Iwo Jima and retired in 1950 after attaining the rank of lieutenant general.

World War II-era Army amphibious doctrine also reflected the influence of the lessons learned during Grand Joint Exercise No. 4. The second edition of Field Manual 31-5: Landing Operations on Hostile Shores, issued in November, 1944, alluded to General Craig’s concerns following the February, 1932, training on Oahu. The manual included a command structure that included an overall operational commander with subordinate officers to direct ground, air, and naval forces, thus alleviating the command problems expressed by the Blue Army Expeditionary Force commander. FM 31-5 listed air supremacy—a major challenge for the Blue Air Force—as “the first requirement for the success of any amphibious operation.” Fleet Problem XIII demonstrated the lethality and range of carrier strike forces and exposed land-based vulnerabilities. For naval officers, including Admiral Yarnell, the peacetime operation provided evidence to advocate for more aircraft carriers in an era of limited budgets.

Fleet Problem XIII and Grand Joint Exercise No. 4 in February 1932 helped shape the American naval and amphibious operations that were required to turn back and defeat the Axis Powers. The costly but successful seaborne invasion of France in June 1944, and numerous other amphibious landings had their origins in the difficult lessons learned on the shores of Oahu in early 1932.

The strategic situation in the 21st century is similar to that of the 1930s with emerging conventional threats in both Eastern Europe and the Indo-Pacific regions. Likewise, the Army anticipates manpower reductions and decreased budgets while the costs of modernization increase. The exercises in and around Oahu in 1932 exposed capability gaps, tested doctrine, and influenced participants. These factors gained importance in the coming years as the United States approached war and received the resources required to develop a joint, multi-theater amphibious capability. As the Army enters an uncertain and unstable global environment, continued training in peacetime can have a profound impact on future operations in wartime as demonstrated by Army and Navy forces in February 1932.

Shane P. Reilly is a Contract Historical Research Analyst on the Analysis and Research Team, U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

Photo Description: Clockwise from top left: Sailors positioned ashore dragging boats by tow rope onto the beach; 75mm field gun from Battery ‘D’ 76th Field Artillery Regiment being offloaded by motor launch crews from the USS Nevada; Soldiers from the 30th Infantry Regiment disembarking from a motor launch from the USS Arizona temporarily attached to the Blue Army Expeditionary Force during the training; A supply wagon from Battery ‘D’ 76th Field Artillery Regiment being offloaded by motor launch crews from the USS Nevada; Center: Field Manual 31-5: Landing Operations on Hostile Shores that was ultimately informed by many of the lessons and gaps found during the 1932 exercises.

Photo Credit: War Department photos Courtesy of the U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center archives