International leaders might do well to look to an idea from a century ago, when the world was also trying to deal with the global effects of a pandemic and an age of great power competition.

Updated as of 0830/31 Mar 2020

In the middle of confronting the COVID-19 pandemic, everyone’s attention is focused squarely on public health and the economy, as it should be. Sooner or later, however, the international community will need to begin a deep discussion about what the coronavirus pandemic will mean for national and international security. International efforts to improve global human security will surely be a common topic. States will hopefully come together to discuss global pandemic preparedness and capacity building in public health.

But more traditional “hard” security concerns, such as arms control and great power competition, deserve attention as well. International leaders might do well to look to an idea from a century ago, when the world was also trying to deal with the global effects of a pandemic and an age of great power competition. In 1921-22 the great powers came together for the Washington Naval Conference. What they tried to accomplish is at least worth considering today to deal with COVID-19. As with all historical analogies, the parallels are far from exact, but they may give us some insight into one potential way forward to mitigate risk in these unusual times.

Reducing uncertainty should be a primary aim for all of the major players on the world stage as they think through how to deal with the post-coronavirus environment. This new world will likely present significant challenges to at least two of America’s rivals, namely Iran and China. (Russia has been much harder to read during this crisis). The United States and its closest allies—namely France, Italy, Spain, and Germany—will also face enormous recovery costs. All have been hit hard by the pandemic. Now is not the time for nations to look for windows of opportunity to launch aggressive moves. Rather, now is the time for international collective efforts. The global nature of the pandemic and its effects on the international economy may present a chance to solidify a status quo that not all states favor, but all may be willing to accept for a few years while they deal with the fallout from the coronavirus.

In 1921, the American secretary of state, Charles Evans Hughes, invited nine powers to come to Washington D.C. to discuss ways to reduce spending on arms. The basic idea was to force down spending on weapons and reduce great power competition through international treaty. In the aftermath of the First World War and the influenza pandemic, the great powers needed to avoid another costly arms race and the risks of another war that would have come with it. The idea Hughes promoted essentially involved locking in the status quo at a relatively cheap price, both to enhance stability and to prevent any single nation from sparking an arms race.

The Harding administration that Hughes served was deeply suspicious of the League of Nations and the collective international system that it represented. The White House even returned mail from the League unopened. Instead, Harding and most other Republican leaders believed that the path to peace and prosperity involved the nations they defined as great powers coming to agreement outside of the League’s institutions. Doing so would, they argued, keep the interests of the most powerful states at the center. Only by limiting their military spending could an agreement have an impact on the problem at hand.

The Washington Naval Conference produced two key treaties. The first, the so-called Five Power Treaty, set naval tonnage in a ratio. The United States and United Kingdom agreed to limit their fleets to 500,000 tons each; Japan to 300,000 tons; and Italy and France to 175,000 tons each. For the British and the Americans, the deal locked in their naval supremacy at least as measured by the proxy of tonnage. The other powers agreed to these limits because they knew that they would not fall too far behind the Americans and the British. As long as the two powers at the top used their fleets to promote a healthy global commons, the others could accept their smaller status.

The conference’s other main agreement, the Nine Power Treaty, locked in the status quo in China, then at risk of becoming a major scene of great power competition. It kept the so-called “Open Door” in place, allowing all of the powers to trade with China but preventing any of them from further colonization or occupation. It also led Japan to return the Shandong peninsula to Chinese control, thus solving one of the most bitter debates of the Paris Peace Conference. Similar treaties might work today to help stabilize hotly contested areas like the South China Sea and the Horn of Africa if the great powers agreed to respect the borders and statuses as they effectively exist right now.

The treaties produced by the Washington Conference contributed to the relatively peaceful 1920s (at least in contrast with the decades that came before and after). Nevertheless, the system certainly had its downsides. Neither Germany nor the new Soviet Union were included, and Japan in particular benefited from the agreement because the Americans and the British had global commitments that limited how much tonnage they could devote to the Pacific. In today’s world, revisionist powers like Russia might find this idea unattractive and refuse to participate. It would also likely do little to address the global problem of terrorism. Such is the nature of global problems: there is not a single silver-bullet solution. This limitation should not prevent us from exploring any solution that might offer a chance at greater global stability.

Moreover, if a state, even a revisionist state, saw some benefit in locking in the status quo so that it could focus on recovery from coronavirus or other problems, it might see such an agreement as worth exploring. If it worked, a new Washington Conference type of agreement would at least help a state not fall any further behind as a result of recent turmoil. Moreover, non-signatories may recognize the international system and abide by it as the Soviet Union recognized the non-interference in China called for in the Nine-Power Treaty.

Such is the nature of global problems: there is not a single silver-bullet solution.

The world today is obviously not the same as that of a century ago. Still, in this era of uncertainty and increasing great power competition, it might be worth revisiting the basic ideas that informed the Washington Conference. An agreement by the great powers to stop or limit investments in particularly disruptive technologies like hypersonic weapons might be a place to start. Caps on ground forces, naval tonnage, nuclear warheads, and missiles based generally on current levels might be another.

The Washington Conference locked in a status quo for almost fifteen years, until the rise of Nazism and the growth of Soviet power worried the other great powers enough not to renew it. Like all treaties, it was designed with a particular set of problems in mind. As those problems morphed and changed, the treaty became less relevant. Nevertheless, it does present us with a model that might well be adapted to the new and challenging times we face today. A new Washington Conference could stabilize the international status quo today in order to allow the great powers to deal with the effects of coronavirus. It might also provide time for diplomacy to work on some of the most disruptive issues in the global system like the Iranian nuclear program.

As in 1921, no great power would get everything it wants, and it is unlikely that any agreement could stop disinformation and cyberattacks. It is also hard to see states such as North Korea and Iran getting an invitation to such a conference, although their absence might not matter if they saw a value in operating inside (or at least, not explicitly outside) the international consensus. An agreement in the spirit of Charles Evans Hughes could buy time and free up resources for the United States, China, the states of the European Union, and maybe even Russia. There would need to be safeguards and checks in the system to ensure compliance. Such an idea would also run against the goal for NATO members to increase their defense spending to 2% of GDP. Still, there is a precedent and there might be enough agreement worldwide that a new Washington Conference is worth pursuing as one solution to mitigate the damage of coronavirus.

The winners in such a deal would be the states that see recovery from coronavirus as more important than the great power competition issues they had prioritized just a few long weeks ago. I first heard of coronavirus when I was in Ethiopia discussing the nature of great power competition in the Horn of Africa with the new Ethiopian Defence College. Now as I write this, scientists are speaking of Africa as a coronavirus “ticking time bomb.” It is reasonable to presume that African states will need to shift their focus to fighting the pandemic. It is also reasonable to hope that the great powers might see an incentive to reduce the potential for tension in the region.

Even if such a conference produced little of substance, it would at the very least help to allay fears that the United States has not shown global leadership during this crisis. Merely having the conference should provide a forcing function for American leaders to think through how the liberal world order should adapt to the world we are likely to face in the foreseeable future. It would also provide a forum for exploring the friction points between the American viewpoint and those of allies, partners and competitors worldwide. Without such a discussion, the United States can neither promote its vision nor even redefine that vision.

A global conference on the Washington model is, of course, no panacea for the myriad problems we face. We are living in a world that is changing by the hour. Still, an idea from a century ago might just provide us with a model to think about one way to manage the crisis that the coronavirus has given us. The Washington Conference dealt with serious issues and reached agreement against long odds because the great powers needed to find ways to free up resources to solve other problems. A similar environment exists today. Perhaps a similar solution can buy us all some time. How we use that time, of course, will make all the difference between long-term success and failure.

Michael Neiberg is the Chair of War Studies at the U.S. Army War College. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

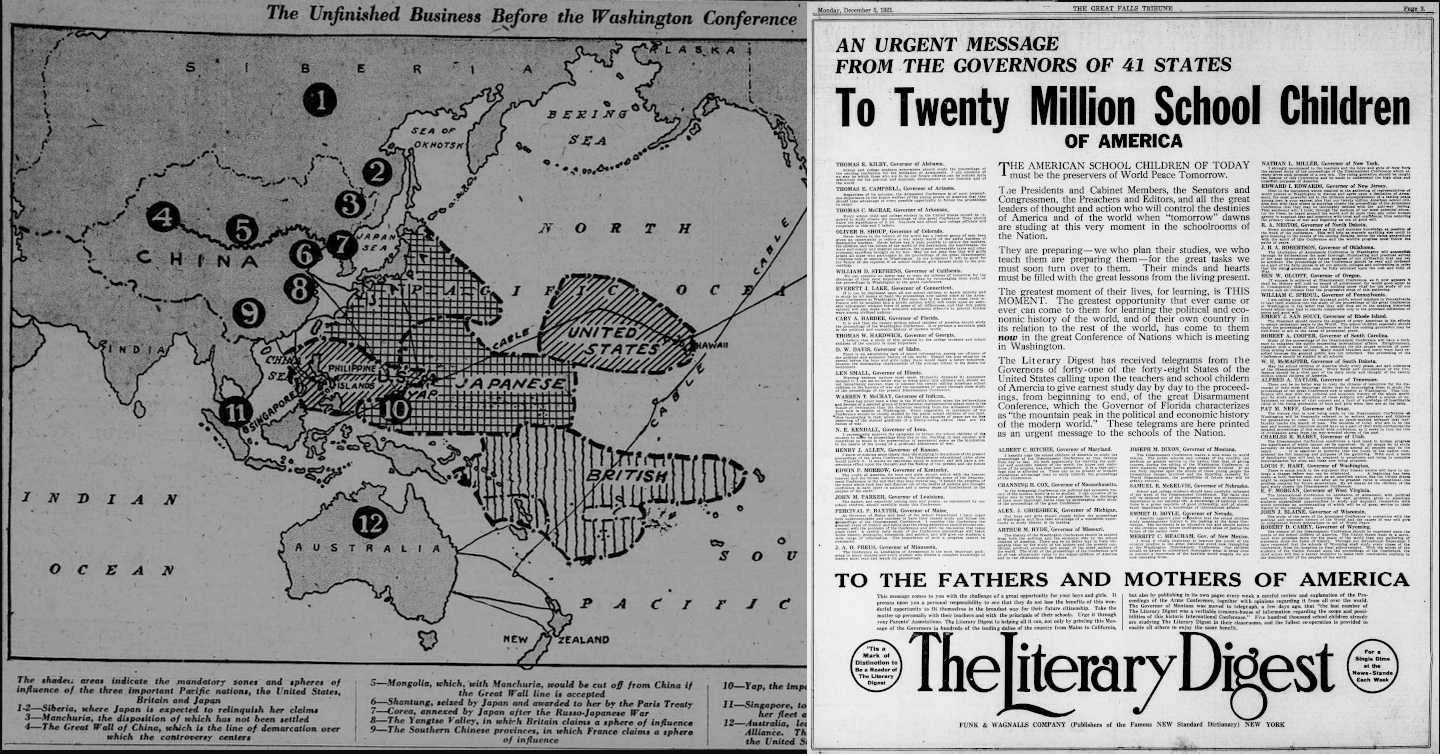

Photo Description: (L) The “spheres of influence” as determined by the Washington Naval Conference. (R) The public plea of 41 U.S. Governors to the students and teachers of the nation “to give earnest study day by day to the proceedings, from beginning to end, of the great Disarmament Conference”

Photo Credit: Library of Congress (L) New York Tribune, November 27, 1921, (R) The Great Falls Tribune, December 5, 1921

Updated as of 0830/31 Mar 2020

Fairly good analysis but you should note that compromised negotiations can lead to a loss of confidence in a national government followed by a serious power change and resurrection of regionally aggressive policies and actions.

Read The American Black Chamber by Herbert O. Yardley and then study its impact on Japan- government by assignation – occupation of North China and ultimately the entry of Japan into WW-II.

Very interesting. I wonder which nation / multinational organization can pull off something like this today when the US is just starting to react to the crisis and the EU has failed to provide support to its members. Maybe China? I think it will be very interesting to see Beijing trying an initiative like this and how the “Western world” will respond.