Chinese leaders have struggled to develop coherent policies toward Eurasia for centuries. And the work of building a policy for the larger Central Asian region has serious implications for the building of the modern Chinese state. Beijing’s efforts to reduce the influence of the Uyghur population of Xinjiang Province is a perfect example of the failing policies of the region. A BETTER PEACE welcomes Zenel Garcia to discuss his latest book China’s Western Frontier and Eurasia The Politics of State and Region-Building. Zenel joins podcast editor Ron Granieri in the virtual studio to examine how China has attempted to handle its western frontier through a series of state-building initiatives. Their conversation looks at how China’s region-building project in Eurasia has been complicated by the collapse of the USSR, increasing globalization, and the party’s professed concerns about terrorism, separatism, and extremism.

These soldiers bring their families along. They’re not just defending a frontier. They’re cultivating. They’re doing trading. They’re trying to create a new community. But then you move fast forward several generations in and you’re slowly changing the demographics of that region and so this is not particularly new. We definitely have seen this play out in pretty much every single dynasty and of course you see it now in the and PRC today.

Podcast: Download

Zenel Garcia is an Associate Professor of Security Studies in the Department of National Security and Strategy at the U.S. Army War College. His research focuses on the intersection of international relations theory, security, and geopolitics. Specifically, how interpretations of security and the geopolitical environment shape the discursive and empirical processes of regional formation and transformation in the Indo-Pacific and Eurasia.

Ron Granieri is Professor of History at the U.S. Army War College and the Editor of A BETTER PEACE.

The views expressed in this presentation are those of the speakers and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, U.S. Army, or Department of Defense.

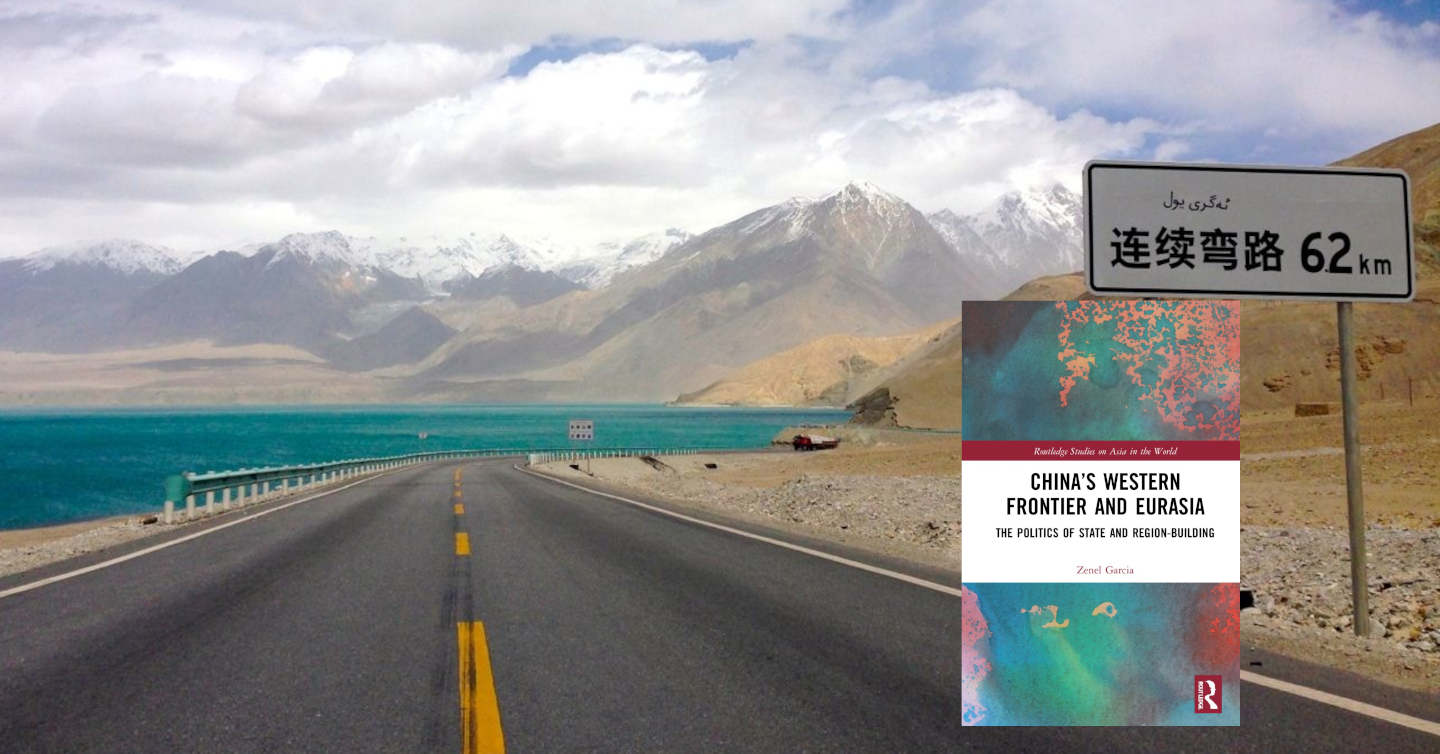

Photo Description: Karakoram Highway at Bulong Lake

Photo Credit: By Mahnoorrana11 via Wikimedia Commons

Excellent discussion. I now have a better understanding of why China is doing what it is in the western border areas. The speaker also touched on Russia involvement in the region and how it sees its projection of Russian power in this area.

If a/the central underlying goal of many nations (for example, the U.S. and China) is maximizing their nation’s economic growth potential,

Then a/the central underlying problem — which stands directly in the way of these nations being able to achieve this such goal — this is the “cultural backwardness” problems that are often found within the states and societies that one hopes to exploit and/or to otherwise do business with and in.

As to these such “cultural backwardness” problems — which stand in the way of “development” — consider the following:

“Where the cultural backwardness of a region makes normal economic intercourse dependent on colonization, it does not matter, assuming free trade, which of the civilized nations undertakes the task of colonization.”

(See the first paragraph of Joseph Schumpeter’s “State Imperialism and Capitalism.”)

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, however, did not think that colonization was the best way to overcome these such “cultural backwardness” problems — which, back in his time and still today — stood/stands directly in the way of achieving “normal economic intercourse” in other countries. In the alternative, Roosevelt thought that something different (which today we might call “nation-building?) was the better way to go, for example, for the “billions were pennies” reasons Roosevelt notes below:

“Imperialists don’t realize what they can do, what they can create! They’ve robbed this continent (Africa in this case) of billions, and all because they are too short-sighted to understand that their billions were pennies, compared to the possibilities! Possibilities that must include a better life for the people who inhibit this land.”

(See the book “Imperialism at Bay: The United States and the Decolonization of the British Empire 1941-1945,” Page 227.)

As to (a) a nation employing its military, police, intelligence (etc.) forces; this, to (b) overcome the “cultural backwardness” problems and achieve “nation-building” in various regions today — as to this such mission, consider the following:

“a. An IDAD (Internal Defense and Development) program integrates security force and civilian actions into a coherent, comprehensive effort. Security force actions provide a level of internal security that permits and supports growth through balanced development. This development requires change to meet the needs of vulnerable groups of people. This change may, in turn, promote unrest in the society. The strategy, therefore, includes measures to maintain conditions under which orderly development can take place.”

(See our very own JP 3-22, Foreign Internal Defense, Chapter II, Internal Defense and Development, Paragraph 2, Construct.)

Bottom Line Question — Based on the Above:

Should we consider China’s efforts — for example in Central Asia, etc., today — these, from the exact same “development”/”overcoming cultural backwardness problems” perspective that our very own JP 3-22, above, seems to take on and address?

This is a very interesting question, although I have to preface two quick things before getting there. The first being that Imperialism and its colonial enterprise inherently generates hierarchic ideas of culture (e.g. civilized vs uncivilized). This is ultimately a subjective judgement, but one which has clear effects on the colonial subject. The second is that state and nation-building are separate categories but which intersect. The former is about building political and economic institutions that provide goods and services, the latter being about generating a national identity. You can have one without the other, and one can undermine the other, but ideally you’d want success in both in order to have a stable state. So to get at your question, in the context of Xinjiang, there is definitely a hierarchic, sino-centric understanding of minorities and their cultures. The CCP has concluded that the modern Chinese state needs state and nation building in these spaces. As I mentioned in the podcast, state or nation-building are not inherently benign and we know that historically this involves direct and indirect violence. In the context of Central Asia, the Sino-centric view remains, but there is little evidence they are interested in nation-building there. However, they are certainly interested in state-building, i.e. giving those states the capacity to build political and economic capacity. From their perspective, greater levels of development there is likely to stabilize the regimes, generate new supply chains and markets, and therefore, facilitate development in China’s interior.

Z.G.: From the end of your reply above:

“In the context of Central Asia, the Sino-centric view remains, but there is little evidence they are interested in nation-building there. However, they (the Chinese Communist Party) certainly is interested in state-building, i.e. giving those states the capacity to build political and economic capacity. From their perspective, greater levels of development there is likely to stabilize the regimes, generate new supply chains and markets, and therefore, facilitate development in China’s interior.”

Question:

But is the CCP’s logic sound here?

In this regard consider that — while the East and West Coasts of the U.S. are certainly well-developed and have been for some time — “fly-over America” (much like “fly-over China?”) remains, comparatively, much less-developed/significantly under-developed. This because “fly-over America” (much like “fly over China”/Xinjiang) remains — compared to the U.S./the West’s East and West Coasts — “culturally backward?” (A controversial statement if there ever was one!)

In the final sentence of my reply above, please change “compared to the U.S./the West’s East and West coasts” to “compared to the U.S.’s East and West coasts.”

Additional Question:

If — due to the reasons I outline above — the basis for China’s activities in Central Asia are not related to facilitating development in China’s interior, then, in the alternative, what might be the reason for China being engaged in this such region?

“But is the CCP’s logic sound here?”

I think it is. In practical terms the CCP cannot pursue nation-building in Central Asia, this is something only the local governments can do, and have been doing since their independence. Facilitating state-building, however, is something they can do and offers tangible benefits for China’s interior. If you trade central government into the interior since the opening and reform period, you immediately face the reality that this is unsustainable in the long term. In other words, once growth slows (which it is), pouring money into underdeveloped provinces becomes difficult if not impossible. And if you believe (which they do) that underdevelopment causes instability, this is an existential problem.

What is the solution then? Ideally FDI into these areas. But if you’re a foreign company, what is your incentive to invest there? The human capital, factories, logistics centers, and transportation hubs are concentrated along the coast. So the best way to incentivize FDI into the interior is by wisely investing in infrastructure and logistics in the interior to attract foreign firms in specific sectors. For example, if you mainly produce products with minimal value-added, then moving inland is not profitable since shipping will be cheaper than rail. However, if you produce higher-end goods, then the cost of rail is offset by a much faster access to markets and greater responsiveness to demand.

How does this apply to Central Asia? Improving the transportation infrastructure and logistics there not only helps transit onwards to European markets, but also generates greater local economic activity which then improves cross-border trade. This is already having tangible effects given that Xinjiang provincial firms are well invested across the region, and Chinese day traders regularly cross the border to conduct business. Assuming this process gradually improves (and one can never make linear projections), then this should produce a more sustainable form of development for the interior of China. Basically, I would argue this is as sound a policy as one can have based on previous efforts.

To your second question on possible alternative explanations, the most obvious to me is simply to prop up the regimes in the region to ensure they do not destabilize China’s western frontier. During the Sino-Soviet split the CCP estimated that nearly 5k incursions into Xinjiang were made by Soviet-backed militias. Spending money in the region ensures a measure of acquiescence. I would argue that both explanations are not mutually exclusive. I argue this much in the book. When I say that the CCP thinks that development and security of Western China is contingent on the development and security of Central Asia (ass Pakistan to the mix), it means they see security and development as intrinsically bound.

Regarding your point on culture, I am bound to disagree with correlating cultural backwardness with underdevelopment. That framing has certainly been a dominant for some time, but that is because a specific form of modernity has been privileged, particularly in the “West.” A lot of research, especially in more critical fields like Postcolonialism, have tackled this correlation and, I would argue, successfully undermined its premise.

Thanks for the engagement, I hope the answers were helpful!

Z.G: Your answers above are, indeed, very helpful and very much appreciated!

However, based on the items that I present below, I am not sure that we should accept China’s rationale, reasoning, justification, etc., as relates to intervening in Xinjiang and/or in Central Asia, such as that “greater levels of development in Central Asia are likely to stabilize the regimes,” “underdevelopment causes instability,” and/or that “security and development are intrinsically bound.” (These, after all, are familiar reasons for Western colonization, imperialism, development, intervention, etc. Yes?)

From Samuel P. Huntington’s famous “Political Order in Changing Societies:”

“The apparent relationship between poverty and backwardness, on the one hand, and instability and violence, on the other, is a spurious one. It is not the absence of modernity but the efforts to achieve it which produce political disorder. If poor countries appear to be unstable, it is not because they are poor, but because they are trying to become rich. A purely traditional society would be ignorant, poor, and stable.”

From David Kilcullen’s “Counterinsurgency Redux:”

“Politically, in many cases today, the counter-insurgent represents revolutionary change, while the insurgent fights to preserve the status quo of ungoverned spaces, or to repel an occupier – a political relationship opposite to that envisaged in classical counter-insurgency. Pakistan’s campaign in Waziristan since 2003 exemplifies this. The enemy includes al-Qaeda-linked extremists and Taliban, but also local tribesmen fighting to preserve their traditional culture against twenty-first-century encroachment. The problem of weaning these fighters away from extremist sponsors, while simultaneously supporting modernisation, does somewhat resemble pacification in traditional counter-insurgency. But it also echoes colonial campaigns, and includes entirely new elements arising from the effects of globalisation.”

If we add to the information provided above the formal admission — found in our very own Joint Publication 3-22, Foreign Internal Defense (see my initial comment above) — that (a) development (b) leads to — not stability but instability —

Then one HAS to ask the begging-for follow-on question, which is:

a. If not stability, security, etc. (which, as ALL my items above seem to indicate, one is willing to SACRIFICE to achieve development, etc.)

b. Then what — actually and truthfully — IS China’s motive for undertaking such (DESTABILIZING/”revolutionary”/ political, economic, social and/or value “change”) efforts and activities as China is contemplating today?

So let’s take a moment to look at the issue of “cultural backwardness;” this, as relates to “development” or — from Schumpeter’s point of view (see my initial “B.C. says: March 8, 2022 at 3:52 pm” comment above) — as relates to achieving “normal economic intercourse.”

Herein, let us focus on — at my second response above (B.C. says: March 10, 2022 at 4:24 pm) — my suggestion of similar “cultural backwardness” problems found in both (a) “fly over” China and (b) “fly over” America.

In this regard, let us consider this from Robert Gilpin’s “The Challenge of the Global Capitalism: The World Economy in the 21st Century;,” therein, see the very first page of the very first chapter (the Introduction chapter.):

“Capitalism is the most successful wealth-creating economic system that the world has ever known; no other system, as the distinguished economist Joseph Schumpeter pointed out, has benefited ‘the common people’ as much. Capitalism, he observed, creates wealth through advancing continuously to every higher levels of productivity and technological sophistication; this process requires that the ‘old’ be destroyed before the ‘new’ can take over. … This process of ‘creative destruction,’ to use Schumpeter’s term, produces many winners but also many losers, at least in the short term, and poses a serious threat to traditional social values, beliefs, and institutions. … (These) threatened individuals, groups or nations (in turn) constitute an ever-present force that could overthrow or at least significantly disrupt the capitalist system.”

(Items in parenthesis above are mine.)

Bottom Line Question — Based on the Above:

From the above, might we consider that — in both “fly over” China and “fly over” America —

a. “Traditional social values, beliefs and institutions,” these

b. Tend to stand in the way of “normal economic intercourse”/”development,” this

c. In ways that these such matters (again, traditional social values, beliefs and institutions) do not stand in the way of “normal economic intercourse”/”development in China’s and/or America’s more market-oriented/more-development-focused coasts?

(From this such perspective, of course, whether we are talking about “fly over” America and/or “fly over” China, [a] “normal economic intercourse”/”development,” this requires [b] that a country work to move their “culturally backward” populations [1] more away from such things as “traditional social values, beliefs and institutions” and [2] more towards cosmopolitan and globalization-focused values, beliefs and institutions. This such effort, in many cases and as our very own JP 3-22 points out (see my initial comment above), often requires the use of “force?”)

How excellent this discussion is! Thumbs up for the informative posts here about the topic of war in the world. I have often read updated news related to the hottest military events from some apps on apkfun.com. Today I have known new source of learning new things here.