If he didn’t do that, he should have.

If you’ve ever spent any time with historians you know that they are the worst people to watch a movie with. Custer never said that, Roosevelt didn’t jump up from his wheelchair, there was no grass on that battlefield in 1917. A BETTER PEACE gathered three of our senior editors to lay waste to some of your favorite historical movies. Tom Bruscino, Jacqueline Whitt, and Ron Granieri sit down for a water cooler style discussion and tell us why we should be miserable watching movies like they are.

Podcast: Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | Blubrry | Podchaser | Podcast Index | TuneIn | Deezer | Youtube Music | RSS | Subscribe to A Better Peace: The War Room Podcast

Thomas Bruscino is an Associate Professor in the Department of Military, Strategy, Planning and Operations at the U.S. Army War College and the Editor of the DUSTY SHELVES series.

Jacqueline E. Whitt is an Associate Professor of Strategy at the U.S. Army War College and the Editor-in-Chief of WAR ROOM.

Ron Granieri is an Associate Professor of History at the U.S. Army War College and the Editor of A BETTER PEACE.

The views expressed in this presentation are those of the speakers and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, U.S. Army, or Department of Defense.

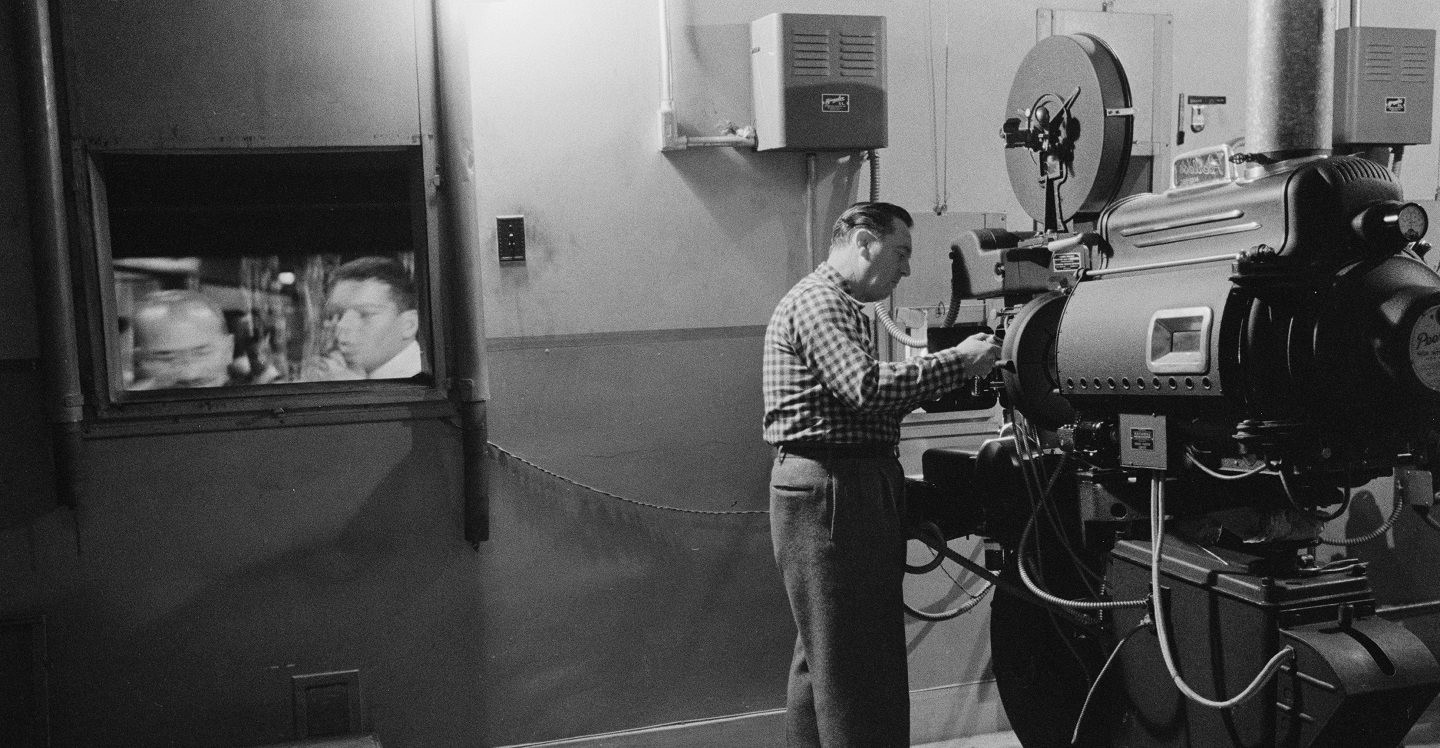

Photo Description: Man working with a projector in a movie theater 1958

Photo Credit: This work is from the U.S. News & World Report collection at the Library of Congress.

If you really want to know what’s wrong with movies about Vietnam, check out Vietnam at the Movies, by Col. Michael Lee Lanning.

Longley, Herring, Brigham, and Marilyn Young, et al…what nothing from anyone who actually went to Vietnam or, otherwise, has a different viewpoint? Very one-sided information for students of the War College (West Point, etc). No wonder the same mistakes are so often repeated, including thinking that what they view in the movies are real depictions of how things were.

Thank you, Bob. There are a whole lot of assumptions and inferences built into that last paragraph, most of them wrong. Aww heck, just take a look here: https://claremontreviewofbooks.com/digital/another-vietnam/

Narcissism (as you wrote in your article) is it? In quoting ‘journalist and academic’ Todd Gitlin you neglected to mention that he was also a president of the SDS, an organization whose leadership were ideologically supportive of North Vietnam and the Viet Cong:

“My generation of the New Left — a generation that grew as the [Vietnam] war went on — relinquished any title to patriotism without much sense of loss. All that was left to the Left was to unearth righteous traditions and cultivate them in universities. The much-mocked political correctness of the next academic generations was a consolation prize. We lost — we squandered the politics — but won the textbooks.” — “Varieties of Patriotic Experience,” in George Packer, ed., The Fight is for Democracy, Harper Collins, 2003.

Narcissism? No, just as Gitlin stated, the New Left ‘won’ a textbook war. As a consequence, their textbook triumph is as manifest today in the fields of journalism and academia as it is in Vietnam War filmography. As with those of similar political persuasion, such as Professor Howard Zinn (who made trips to North Vietnam with other left-wing radicals), there is but one way to look at Vietnam – not as the way it actually was, but with a decidedly anti-American slant. It is an ideological perception reified even within our prestigious military education institutions (which have produced the cultural phenomenon of the “Commie Cadet” and a plebe history course rightly, if derisively, entitled, the “I hate America” course).

It appears that teachers and instructors know little of what really happened to the people of Indochina in the wake of what Gitlin calls leaving South Viet Nam “to its own devices.” Today’s educators are patronizingly dismissive of those of us who served in Viet Nam, and particularly so if we reject the prevailing orthodoxy. That we continue to reject it is not a consequence of ‘narcissism’ or impending ‘dotage’ but a direct result of our professional and personal knowledge of the South Vietnamese and our compassion for their plight in the wake of a disgraceful US withdrawal. With regard to the so called orthodox v. revisionist ‘debate’ and given the profound impact of the New Left’s ‘textbook’ victory upon American consciousness, it is unacceptable to declare “a plague o’ both your houses” and argue that the history of the Vietnam War is best forgotten.

https://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/dulce-bellum-inexpertis-war-sweet-those-who-have-never-experienced-it

There are a number of issues when considering what to say and how to make a war movie. First, a film maker would need an accurate historical record to begin with. In Misremembering the Holocaust: The Liberation of Buchenwald and the Limits of Memory, George R. Mastroianni identifies the problems historians face starting of page 122. It is not clear that all historians always use the correct methods to construct an accurate history. Memory requires three steps: encoding, storage, and retrieval. With the stress of battle and time memories can fail. An important element is “Social Correction” which S. L. A. Marshall used to reconstruct battles.

Next film makers may fail to understand the psychology of performance. The books The Warrior Mindset: Mental Toughness Skills for a Nation’s Peacekeepers and On Combat provide resources on when and what level of enthusiasm and energy are needed for a specific combat tasks.

In Is our Culture Rotting? How Do America’s Elites Stack Up? The American Interest Vol. XV No. 4 Seth D. Kaplan lays out a framework for deciding whether elites are, “Hubristic, aloof, and self-dealing – or humble, rooted, and self-sacrificing?” Using that framework, we would say this was true of the British Army before both WWI and WWII. As Captain B. H. Liddell Hart explained in his memoirs Vol. I and Vol. II, the elites of the British Army in the calvary regiments viewed the army more as a social club and not as force fight England’s enemies. Evelyn Waugh gave a fictional account of rotting culture in Men at Arms, Officers and Gentlemen, and Unconditional Surrender.

In Nobody Knows Anything essay by William Voegeli Clairemont Review of Books, Vol. XX No. he points to a classic quote from William Goldman the screen writer. He said, “Nobody knows anything.” That is, “nobody, nobody – not now, not ever – knows that lead goddam thing about what is or isn’t going to work at the box office.” The problem is that people immerse themselves so closely in learning the mechanics of film making and only associating with others in the film industry that they lose touch with the ordinary man or woman and what they like. The obvious parallel is our armed forces spends all its time learning our strategy and tactics so that they lose touch of what it is to fight a war among peoples. They lose touch with what it is to fight a foreign culture.

In The AEF Way of War Mark Ethan Grotelueschen describes how various divisions in the AEF adopted the tactics learned from the British and the French. Some division commanders were more successful in adapting to the new conditions. Unfortunately, General Pershing never understood the needed changes. Then the AEF lacked a process of systems analysis of battles such as S. L. A. Marshall was able to do. In How Behavior Spreads: The Science of Complex Contagions Damon Centola describes how the new tactics might have spread through out the AEF.

Unfortunately for the film industry and our Armed Forces social contagions can adversely affect policies and staffing. In The Madness of Crowds: Gender, Race, and Identity by Douglas Murray describes how various trends in society can be carried to extremes that it is similar to social media lynch mob. Those trends will deform film making as the film industries seeks to portray war films in terms of the current social justice theories.

Dr. Buscino, your article at Claremont is really excellent. This from a Vietnam vet, activist amateur historian of the “revisionist” school. In debates about the war, I use the Gordian Knot argument, which goes like this. Never mind anything about the war itself, let’s examine the results of the final victory by Hanoi, using of course more aid from Russia than the South got from us.

When a war ends, what happens? In WW2 the showers of Zylon B stopped running, the horrific treatment of conquered people by the Japanese stopped, and people started rebuilding lives in comparative freedom all over. So we could all feel pretty good about the struggle and sacrifice and our morality in the fight.

In South Viet Nam several tens of thousands were executed, 1.3MM went into “re-education” where many thousands more died, all civil liberties were gone, everyone who worked for RVN in any capacity became subject to official discrimination for themselves, their children, and grandchildren, and for the first ten years, there was near starvation. Things were so bad that 2 million people fled, at the risk of at least a 25% death rate, even including refugees from the North who went to China. Today the country is well known for its oppression of all dissent and enormous levels of corruption.

So the question of who were really the good guys bringing “liberation and justice” to the South seems to have been answered very definitively.

Were JFK’s words that we would fight any foe and bear any burden for the cause of liberty, not just for ourselves, but others as well, false and foolish? Many of us believed in that then, and that’s why we went, and that’s why we are sad about the eventual outcome, and remain strong in our view of those events.