“The crisis the world faces today [1993] is the absence of a Third Wave peace-form that corresponds to the new conditions of the world system and to the realities of the Third Wave war-forms.”

War and Anti-War was among the many relatively popular military and national security books of the very fresh post-Cold War geopolitical landscape that claimed to explain and offer suggestions for managing life in this this “New World Order.” It also attempted to restrain some of the early-1990s ecstasy caused by having apparently woken up from history: depending on the edition the subtitles were either “Making Sense of Today’s Global Chaos” or “Survival at the Dawn of the 21st Century,” neither of which implies a rose-colored outlook on the present or near future.

The book’s 30th anniversary this year is an opportunity to review its predictions and prescriptions, and in particular, to reflect on whether its Anti-War/Peace Form recommendations have been tried and found wanting, or as GK Chesterton wrote of the Christian ideal, have been found difficult and left untried.

Riding Waves

Alvin Toffler came to international attention in 1970 with his book Future Shock, defining the phenomenon that people were (and are) perceiving that they are experiencing too much change in too short a period of time. Later writings, which added his wife Heidi as co-author, included 1980s’ The Third Wave. It posited that “First World” societies had in the 1950s transitioned from a Second Wave industrial economy into a Third Wave information- and knowledge-based economy (both following a very long First Wave agricultural economy), and that many of the cultural norms and governments of those societies hadn’t yet adapted to this change. Their books were international bestsellers, establishing the Tofflers as household-name futurists, and influencing business and political leaders. By the early 1980s, the Tofflers’ work had also begun to influence the thinking of some influential members of the U.S. military. And by the early 1990s, the transforming U.S. military had begun to influence the thinking of the Tofflers. Much of War and Anti-War is taken up applying, or speculating about, how the Toffler’s Third Wave concept would impact the U.S. military and those it would have to fight with and against.

The book works well enough in 2023 as an easily digestible peek into the intellectual ferment happening in the early 1990s U.S. military. Its real value to the modern reader is in its framing of the problem with winning wars, accomplishing objectives, and more importantly, keeping peace during an era of dramatic change.

War and Anti-War makes the case that for the past two centuries or so, First Wave societies had, when fighting or competing with Second Wave societies, usually lost both wars and wealth. The authors argued that that with the coming of the Third Wave, “Second Wave war, like Second Wave economics, was racing towards obsolescence.” Nations – or organizations, or corporations – make war the way they make wealth, and thus the models and thinking based on the armies of Napoleon, Grant, and Eisenhower, and the industrial output of 1940s shipyards in Brooklyn, Yokohama, and Bremen, were losing their relevance and utility. Nation-states – including the United States, and international organizations composed of nation-states – were no more prepared for this ongoing change in war than older corporation giants were for the similar processes.

A New World Order and Matching Peace Forms

“Welcome…to the new global system of the 21st century,” the Tofflers write. “In it we can see the powerful process of trisection at work, reflecting the emergence in our lifetimes of a new civilization with its own distinct survival needs, its characteristic war-form, and soon, one hopes, a peace-form [a new set of tools … for preventing war or mitigating violence] to match.” First Wave peace forms included tribal champions fighting one another – think David and Goliath – with their respective sides abiding by the outcome and thus stopping at a duel as opposed to a war. Second Wave forms included legal restraints and norms applied toward non-combatants and medical professionals. The authors argue that the world is still collectively stuck with peace forms of earlier waves, while the U.S. and much of the globe are already riding the next one. The most important ideas within this book are contained within its list of proposals for these updated peace forms. Grouped broadly, they are:

- For-hire stability operations

- Increasing transparency

- Tracking weapons technology

- Assassination of key individuals

- Incentivizing the trade of weapons for non-lethal technologies (or money)

- An anti-war media campaign (“rapid reaction contingency broadcasting force”)

In the decades since War and Anti-War was released, all of these have been attempted in part – at times like the wars they try to stop in conjunction with peace forms from older waves – with varying results. Some of that variance lies in the Tofflers’ analysis of this “New World Order” and how some technologies would evolve, some in the form’s piece-meal execution.

Certainly less assured of the end-of-history than some of their futurist peers, in this book the Tofflers promote the conventional wisdom that connecting technologies will promote peace. We’ve since learned that videos of beheadings and disinformation campaigns can run on public, free software come with that connectivity, too. “Poverty is no friend of peace,” the author’s quote. True, but wealth is not always an enemy of violence. Third Wave nations, unlike agricultural societies, have no need to acquire new territory through violence, the Tofflers write. But one of the current great powers with which the United States is currently competing has invaded the land of a neighboring, non-threatening country, and the other competing great power is continuously planning and threatening to do something similar to one of its neighbors. Taking other nations’ real estate by force may be perceived by leaders – not countries, necessarily, but at least of few of their leaders – as being a reasonably valuable object to pursue.

It’s difficult to count the number of wars that didn’t happen in the last 30 years, and peace forms, however well they’re executed, don’t promise a total absence of conflict or violence. The actual amount of state-based conflicts – which doesn’t speak to amount of violence or suffering per conflict but does at let us know that prevention has failed–tells a disheartening story. According to one source, there were 37 civil conflicts without foreign intervention, six civil conflicts with an intervening foreign power, and no wars between states or those that could be called “imperial” as War and Anti-War first arrived on booksellers’ shelves. Twenty-eight years later, there were 25 conflicts with foreign intervention, 28 without, and three between states. The depressing trend continues into 2023: the headline for a story about the UN Security Council meeting of January, 2023 read “With Highest Number of Violent Conflicts Since Second World War, United Nations Must Rethink Efforts to Achieve, Sustain Peace, Speakers Tell Security Council.”

Found Wanting or Left Untried?

The Toffler’s would not be surprised by this record of the UN’s impotence in peacemaking and peacekeeping, nor by the need to “rethink efforts.” The UN was called out by the authors in a subsection of the book for its decidedly Second Wave ways, and despite the claim cited above, peacekeeping operations since 1993 have had mixed effectiveness at best. As of this writing, the UN’s largest such mission is ending, partially due to its inability to counter Third Wave War forms. In the decades since War and Anti-War, the U.S. military’s record at winning wars and maintaining peace has also been, to be generous, inconsistent and indecisive. Not all of the world is riding the Third Wave, of course: it’s here already, just unevenly distributed, and the challenges with war and peace-form transitions are still apparent, and lend validity to the war and anti-war theme.

The Third Wave peace forms which have been used have also yielded mixed results. If their purpose, however, is to stop short of war, even those forms used by malign or rogue actors for criminal reasons could be deemed successful. Politics by other means involving violence, yes, but a general mobilization, invasion, or bombing campaign is avoided. Anti-War is not exactly peace: it may however be better than some of the alternatives, including continuing the steady trend of more conflicts each year than the last. As such, a review or revisit of this old book still has the potential to help in surviving in this dawn (now “midmorning”?) of the 21st Century, making sense of ongoing global chaos, and in reminding the reader to keep working towards some admittedly difficult ideals.

J. Overton is the editor of Seapower by Other Means: Naval Contributions to National Objectives Beyond Sea Control, Power Projection, and Traditional Service Missions, and a former Non-Resident Fellow with the Modern War Institute at West Point.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

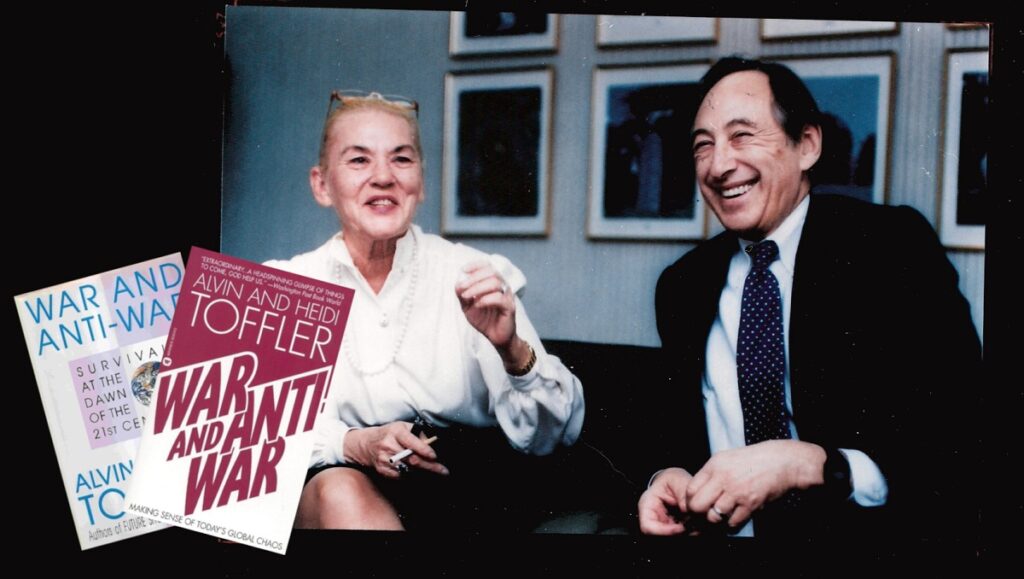

Photo Description: Heidi and Alvin Toffler in Japan in 1990

Photo Credit: Photographer unknown.