“The intelligence is clear: Beijing intends to dominate the U.S. and the rest of the planet economically, militarily, and technologically.”

In the contemporary age of non-kinetic warfare, no adversary poses a greater geostrategic threat to American interests than the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Harvard political scientist and professor Graham Allison describes the present Sino-American contest as a classical Thucydidean rivalry; that is, an apparent predisposition toward conflict between nations, when an emerging power threatens to displace a reigning hegemon. Beijing’s great power status was truly only recognized in 2014, when it both unveiled its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and dethroned the United States as the world’s largest economy, based on its purchasing power parity. Former Director of National Intelligence John Ratcliffe’s recently published editorial presents additional evidence indicating Chinese global, hegemonic ambitions. He wrote, “The intelligence is clear: Beijing intends to dominate the U.S. and the rest of the planet economically, militarily, and technologically.” If so, an examination through the lens of great power competition is needed to analyze the challenges the BRI presents, identify the emerging opportunities associated with a post-pandemic geopolitical climate, and ultimately pinpoint the ideal strategic approach to combatting Beijing’s aggressive economic overtures. A glimpse into a single node along the BRI in Africa may shed light on China’s global ambitions.

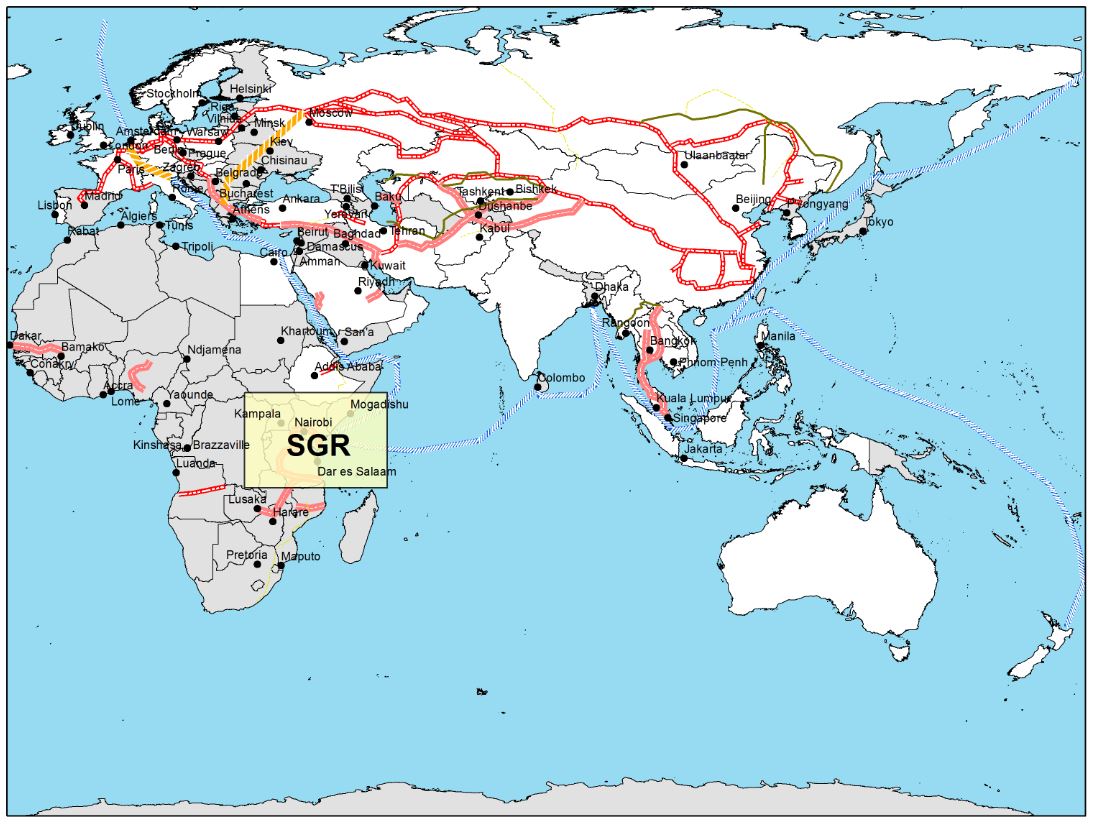

Historically unparalleled, the BRI is a $4 trillion venture that includes: 790 infrastructure projects and 71 countries, encompassing 70% of the world’s population, 55% of global economic output, and 75% of the planet’s energy reserves. The BRI’s framework stems from the Silk Road, which connected China to Europe for nearly 2,000 years. The positive influences the Silk Road had on global prosperity is well documented, as it facilitated the exchange of goods, philosophies, cultures, and technologies between eastern and western civilizations. This history provided the foundation for the BRI’s marketing campaign – an initiative to build a more interconnected world and to enhance global prosperity.

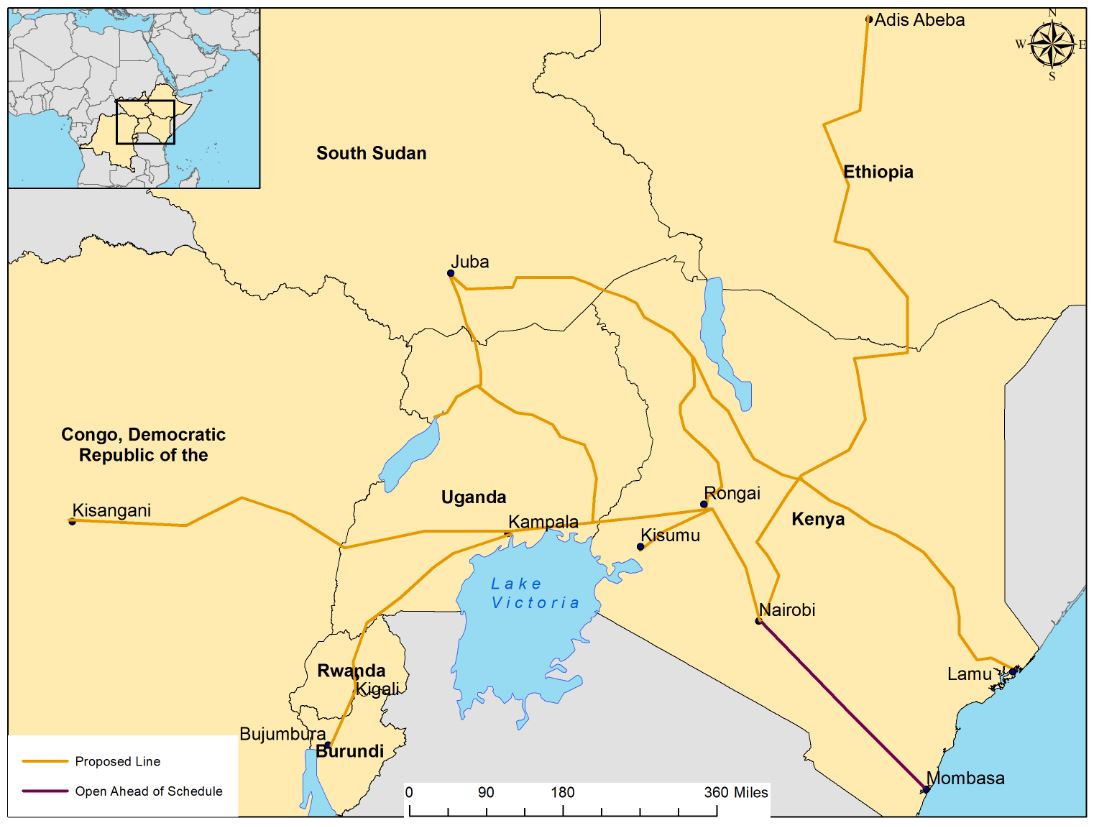

Today, Beijing intends to establish a multi-domain Silk Road by 2049 – the PRC’s 100th anniversary. Moreover, in 2017, the Chinese Communist Party amended the country’s constitution and incorporated the BRI as a core element of its “100-Year Plan.” The BRI is comprised of three symbiotic belts: the Silk Road Economic Belt, the Maritime Silk Road (MSR), and the Digital Silk Road. The MSR, through the Mombasa-Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway (SGR), is critical to connecting this cross-continental trade network to the most resource-rich continent on the planet: Africa. Once complete, the SGR will connect seven countries to the Mombasa Port.

The SGR is expected to provide economic benefits to both the investment countries and to their trading partners. To support this assessment, there are numerous historical examples of catalytic railways that directly enabled a nation’s ascent to world power status. For example, the U.S. Transcontinental Railroad, completed in 1869, led the country to rapid industrialization and a rise to global prominence. In 1916, Russia became a world power when it completed the 7,500 km Trans-Siberian Railway. This critical piece of infrastructure directly facilitated Soviet industrialization, as well as the rapid mobilization of military forces to the Soviet Eastern Front in WWII. Even today, highly efficient railways, measured in tonne-kilometers (tkm), continue to serve as reliable metrics of global power status. As expected, the three leading world powers also have the highest tkm – the United States, China, and Russia.

The Mombasa-Nairobi branch of the SGR is Kenya’s $3.6 billion cornerstone of the BRI-MSR project. Currently, Exim Bank of China holds 90% of the project’s debt, allowing China’s Road and Bridges Corporation to maintain and operate the SGR until 2027. The SGR will turn the Mombasa Port, which facilitates 80% of East African trade, into a global trading hub, connecting six countries to the MSR via Kenya. As of June 2017, only 5% of cargo from Mombasa’s port moved by rail, a number Kenya aims to boost to 40% by 2025. In addition to the Mombasa – Nairobi line, the five branches of the 3,200 km SGR will connect the port to Malaba, Kisumu, Moyale, Lamu, and Nedapal. Current estimates suggest that completing the SGR will provide significantly cheaper transportation to and from the Mombasa port – the overall cost cut is projected to be 40% for cargo and 60% for commuters. Kenya’s Transportation Minister claimed the SGR would instantly increase GDP by 1.5%, allowing Kenya to repay Chinese loans in four years.

Despite the BRI’s marketing campaign, the initiative has no shortage of critics, as many believe that Beijing operates under the pretense of spreading prosperity, while actually aiming to centralize global trade. Some have gone as far as to label Beijing’s practices of luring underdeveloped countries into untenable financial obligations, as an intricate form of debt-trap-diplomacy. And in fact, despite the SGR’s positive projections, as of 2020, the development has failed to produce any meaningful profit.

Today, several aspects of the project’s design and implementation are under scrutiny. The 2014 contracts revealed several oversights that led to the project’s stagnation, including no competitive bidding process, construction costs three times the international standard, and overall costs that are quadruple the project’s initial estimates. These inflated costs, coupled with the railway’s inability to generate profit, led to Kenya’s inability to meet its financial obligations. With only the Mombasa-Nairobi portion of the SGR being complete, construction was halted in 2019, when China withheld the remaining $5 billion needed to complete the other five branches. While withholding additional funding due to payment delinquency is standard practice among lenders, the initial decision to finance a multi-billion dollar project, to a country with a 50% debt to GDP ratio should have raised some red flags.

In 2018, a leaked report from within the Kenyan government revealed that its officials signed a sovereign immunity waiver, allowing the Mombasa Port to serve as collateral for the Chinese loans.

Currently, Kenya’s Chinese-owned debt stands at $50 billion, accounting for 72% of all external debt and a staggering 68% of its GDP. Kenya is required to repay this balance by 2024, making it one of the most vulnerable countries to losing strategic assets to Chinese creditors. In 2018, a leaked report from within the Kenyan government revealed that its officials signed a sovereign immunity waiver, allowing the Mombasa Port to serve as collateral for the Chinese loans. In June 2020, this information was a key consideration in the Kenyan Appellate Court’s ruling that the SGR contract was constitutionally illegal. Should the cost of repayment become unsustainable, Beijing will be free to seize the strategic infrastructure in question as collateral.

This risk was validated in 2017 when Sri Lanka, unable to repay the loans on its Hambantota Port, leased 70% of it to a state-owned Chinese merchant company for 99 years. Mombasa Port is the next key piece of strategic infrastructure at risk of being seized.

Many BRI investment countries are facing significant financial hardships, due to both Beijing’s predatory lending and the COVID-19 pandemic. To date, the pandemic has caused a record number of countries to request various forms of debt relief from Chinese lenders. In response, on June 10, 2020, China officially suspended the debt repayments of 77 low-income countries, with Kenya among them. Though it’s still likely the BRI was designed partly to lure investment countries into untenable debt, to seize strategic infrastructure, it is highly unlikely Beijing was prepared for the international financial hardships faced in 2020. Nevertheless, its regional interests chugged on…

East Africa’s strategic value is centered primarily on natural resources. While the region is rich in many common elements which are critical to the defense, manufacturing, and technology sectors, it also holds significant rare earth element (REE) deposits. Despite owning only one third of the world’s REE deposits, the PRC supplies 80% of all U.S. REE imports and controls 90% of their global production. According to then Lieutenant Colonel Eugene Becker (2011) the importance of REE cannot be overstated, as “Rare earth elements are a key ingredient in high-technology products…critical to defense, energy and other industries that impact national security and economic viability.” In 2019, the Department of Defense identified Beijing’s near-monopoly over these critical supply chains as a direct threat to U.S. national security and, in an attempt to diversify its supply chains, started talks with several East African REE mining companies. Yet talk is cheap.

If Ratcliffe’s assessment of China’s ambitions is correct, then as a nation, the United States currently finds itself at an inflection point. It must either uphold the current, Western, liberal world order it helped establish — which in theory rests on values which emphasize fairness — or it must allow revisionist powers to displace U.S. global hegemony.

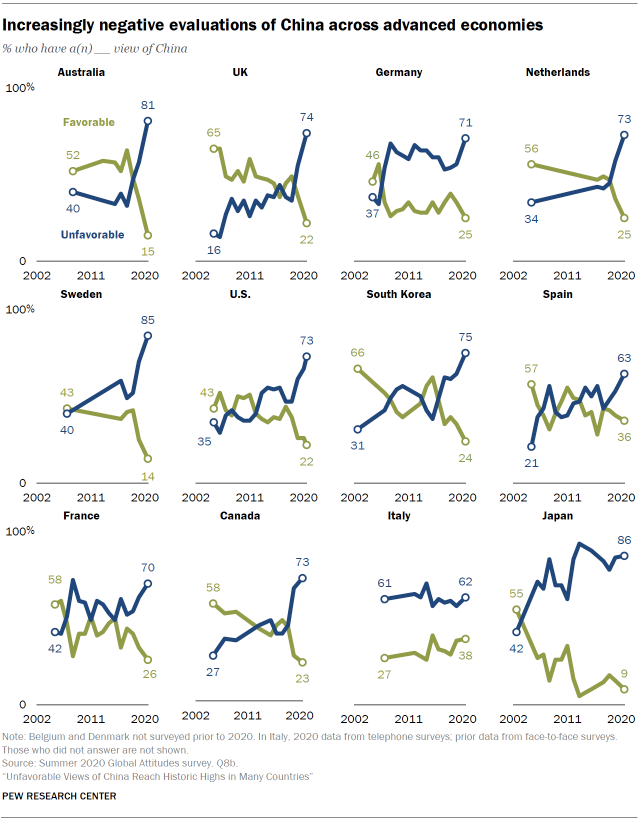

In 1945, during the United Nations’ foundation, Winston Churchill famously said, “Never allow a good crisis to go to waste.” Today, policymakers continue to analyze the post-pandemic geopolitical climate and associated strategic opportunities. The global rise in anti-Chinese sentiment in 2020 illustrates one such opportunity – building an international coalition to combat the BRI. Despite its predatory lending tactics, much of the current disdain toward Beijing is attributable instead to its deliberate information suppression during the early days of the pandemic.

The BRI presents a complex problem set, which warrants an equally sophisticated response, one that integrates multiple elements of national power. A successful strategy against it requires a strategic-level, interagency approach that sequentially leverages American soft power tools and occupies multiple points on the non-kinetic conflict spectrum. The desired end state(s) are to eliminate the lien on Mombasa Port, complete the remaining five SGR lines, economically unify the seven SGR countries, and ultimately dismantle Beijing’s near-monopoly on REE. Achieving these goals will significantly increase the trade, GDP, and independence of Eastern Africa, enabling Kenya and its neighbors to generate the income needed to repay their outstanding Chinese-owned debt.

As the global leader for over 75 years, the United States must prepare for the next era of great power competition, which no longer relies solely on fighter jets, aircraft carriers, and nuclear arsenals; but rather, it depends on economic power and influence. While our adversaries change with time, their fundamental strategies do not – to gain national power parity and to become new global hegemons.

China’s grand strategy is to methodically isolate and successively transcend each U.S. element of national power, starting with its economy. Beijing’s near-monopoly on REE, for example, directly threatens the most asymmetric element of U.S. national power — vis-a-vis China’s power – the military. To ensure the United States is postured to influence this inflection point to its advantage, it is imperative that it rapidly identify and seize strategic opportunities against emerging threats. By leveraging a combination of national power instruments, through multiple points on the non-kinetic conflict spectrum, the United States can present Beijing with a series of complex and seemingly unsolvable strategic dilemmas, along all the BRI’s ‘belts’ and beyond.

CPT David M. Tillman is a graduate student at Northeastern University College of Professional Studies and currently serves as the Information Collection Manager for the Bastogne Brigade of the 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault). He previously served as a Collection Manager, Platoon Leader, and Assistant S2 with the 3rd Armored Brigade Combat Team of the 4th Infantry Division. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

Photo Description: Mombasa Terminus is a railway station on the Mombasa–Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway (also known as ‘Madaraka Express’) located in Mombasa, Kenya.

Photo Credit: Macabe5387 via Wikimedia Commons under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

The problem for the capitalist/the more-developed world today, this is that these folks (whether they will admit it or not) seem view things such as China’s Brick and Road Initiative in exceptionally positive terms, for example, as famous economist Joseph Schumpeter, in the early 20th century, appears to be addressing below:

“It may be stated as being beyond controversy that where free trade prevails no class has an interest in the forcible expansion as such. For in such a case the citizens and goods of every nation can move in foreign countries as freely as though those countries were politically their own – free trade implying far more than mere freedom from tariffs. In a genuine state of free trade, foreign raw materials and foodstuffs are as accessible to each nation as though they were within its own territory. Where the cultural backwardness of a region makes normal economic intercourse dependent on colonization, it does not matter, assuming free trade, which of the ‘civilized’ nations undertakes the task of colonization. Dominion of the seas, in such a case, means little more than a maritime traffic police. Similarly, it is a matter of indifference to a nation whether a railway concession in a foreign country is acquired by one of its own citizens or not – just so long as the railway is built and put into efficient operation. For citizens of any country may use the railway, just like the fellow countrymen of its builder – while in the event of war it will serve whoever controls it in the military sense, regardless of who built it. … ”

(See Joseph Schumpeter’s 1919 “State Capitalism and Imperialism;” the first paragraph.)

In discussing “colonization,” above, what Schumpeter seems to be addressing are the two “infrastructure” deficits found in most less-developed countries — yesterday as today — “infrastructure” deficits which — then as now — (a) stood/stand in the way of “normal economic intercourse” and, thus, (b) had/have to be corrected by SOMEONE in the capitalist/the more-developed world. These such infrastructure deficits of course being:

a. The physical infrastructure deficit (lack of roads, bridges, ports, etc.) — necessary for “normal economic intercourse” to be both achieved and sustained — and

b. The cultural infrastructure deficit (lack of capitalist ways of life, ways of governance, laws, values, institutions, etc.) — which must be “westernized” (or at least ruled by “Westerners”) if “normal economic intercourse” is to be realized.

Bottom Line Thought — Based on the Above:

Thus from the perspective of the capitalist/the more-developed world today (whether they will admit it or not), China’s Brick and Road Initiative appears to be a true “gift from God;” this, given that same is designed to address at least the physical infrastructure deficit that I note above; this, to the benefit of the entire world?

(And therein, as they say, lies the “rub?”)