Operational art had become all-encompassing, because the Joint community called all war making at the national and theater level ‘campaigns.’

Ten years ago, Australian defense experts Justin Kelly and Michael Brennan published scathing critiques of American strategic thinking in Alien: How Operational Art Devoured Strategy and “The Leavenworth Heresy and the Perversion of Operational Art”. In those papers, both published by imprints of the United States military, the authors leveled their ire at a distorted and malignant version of American operational art which, in their view, had gobbled up strategy. The effect, maybe deliberate, was to separate and exclude policymakers from military activities.

The problem could be boiled down to a phrase in FM 100-5 Operations (1982): “The Operational Level of War involves planning and conducting campaigns.” For Kelly and Brennan, this was the heresy, because the design and execution of campaigns was rightly the exclusive and primary role of strategy.

In terms of the disappearance of military strategy, they had a point. Operational art had become all-encompassing, because the Joint community called all war making at the national and theater level “campaigns.” Even worse, ‘campaigns’ expanded outside the realm of armed conflict, and became the official form for peacetime activities of high-level commands: ‘Command Campaign Plans,’ ‘Joint Strategic Campaign Plan,’ ‘Global Campaign Plan.’

Since campaigns defined everything that militaries did in peace and war, operational art governed everything militaries did in peace and war. The Joint definition of operational art said so: “Operational art is the cognitive approach by commanders and staffs—supported by their skill, knowledge, experience, creativity, and judgment—to develop strategies, campaigns, and operations to organize and employ military forces by integrating ends, ways, and means.” These capacious definitions of campaigns and operational art left no room for strategy, whether that be military strategy in war or the various grand and national strategies of the policy realm.

Kelly and Brennan were on to something, but there were two major flaws in their argument. First, they were wrong about the motive for developing and teaching operational art within the Army and at Leavenworth. Few, if any, wanted to use operational art to exclude policymakers from military action. Rather, the study of operational art was meant to improve large unit military campaigns and operations. A closer look at U.S. Army doctrine leading up to 1982 shows that, if anything, operational art replaced corps, field army, and army group tactics, not higher headquarters strategy.

In fact, at the same time the Kelly and Brennan papers came out, a team at Leavenworth produced a more focused definition of operational art for Army Doctrine Publication 3-0 (2011): “The pursuit of strategic objectives, in whole or in part, through the arrangement of tactical actions in time, space, and purpose.” (Full disclosure: I was on that team.) At that time, while trying to think about operational art for counterinsurgency operations, the working hypothesis was that the levels of command that had to think operationally instead of tactically were lower, not higher.

That mistake connects to a second and larger flaw in their argument, which is that they lost sight of practical application. They connected neither strategy nor operational art to the actual people responsible for strategy and operational art, which left them with a limited view of the roles and responsibilities of higher military headquarters. That gap allowed them to buy into the premise that the military strategist’s primary or even sole role is planning campaigns.

That is not the case, and has not been for a long time, theoretically, doctrinally, or practically. True, strategy historically was generalship—the things that generals and admirals do, especially in command of campaigns. But around the turn of the twentieth century, theorists began to recognize that the roles and responsibilities of generals and admirals had expanded beyond just the campaign to preparing for and conducting the overall war effort or effort in a theater of war.

By the early 1940s, that trend was captured in doctrine, in the section on the War Department General Staff in the U.S. Army’s FM 100-15, Field Service Regulations, Larger Units. That headquarters had at least eight tasks:

- Determination of the enemy’s resources, combat strength, major dispositions, and capabilities.

- Decisions upon and preparation of broad basic plans of campaign.

- Determination of the organization and training required for the contemplated operations.

- Determination of requirements, and allocation and distribution of means.

- Accurate and clear delimitation of the responsibilities of major subordinate agencies.

- Approval or modification of plans and estimates submitted by subordinates.

- Coordination of the activities of the field forces.

- Attainment and maintenance of high morale, and combat and logistical efficiency.

The same manual had a section on theater commands that identified similar responsibilities. Even back then, campaigns were just one part of strategy.

The World War II example is illustrative. In that war, a wide variety of people had responsibility for elements of military strategy. President Franklin Roosevelt, Secretary of War Henry Stimson, chairman of the de facto Joint Chiefs Admiral William Leahy, Chief of Staff of the Army General George C. Marshall, Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Ernest King, head of Army Ground Forces General Lesley McNair, head of Army Service Forces General Brehon Somervell, head of Army Air Forces General Hap Arnold, Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower, among many others, had strategic responsibilities. But their tasks, responsibilities, and dilemmas in winning the war differed, and their approaches to meeting those tasks, responsibilities, and dilemmas had to differ too. All the while, almost none of them had to design and conduct campaigns. For the one who did direct campaigns, Eisenhower, that was nowhere near all that he did.

Operational art did not steal the campaign from strategy. Strategy stopped focusing on just the campaigns. Operational art helped fill that gap.

Senior military professionals knew that they were responsible for strategy, so as strategy grew and morphed, they followed.

THE CARLISLE DERELICTION

But that is not the whole story. If Brennan and Kelly correctly saw a problem—that military strategy seemed to have been replaced by campaigning—but misidentified the cause—operational art—then what was the real cause?

The simple answer is that strategy kept growing. What had once been the domain of generals and admirals in war expanded and took on new meanings. The Second World War, the so-called Cold “War,” nuclear weapons, and the exporting of strategic terminology to the private realm led to strategy metastasizing into its current form, as a catch-all for all thinking about policy, diplomacy, economics, operations, ideology, decision making, plans, positions, perspectives, patterns, ploys, long term advantages, ways of thinking, and so on. Strategy became the stuff of policymakers, businesses, sports teams, video games, financial planning, grocery shopping, and pretty much everything else.

Senior military professionals knew that they were responsible for strategy, so as strategy grew and morphed, they followed. They bought into the idea that strategy meant everything from policy to grocery shopping, so they had to study strategy in all of those forms. Military strategy, how to fight and win wars, became just one topic among many. Even at places where war-making was supposed to have pride of place, military strategy got drowned out by all of the noise.

The net result was that we stopped studying military strategy in any depth, and it was replaced by campaigns-as-wars. Here is a more practical illustration: war planning and war plans are, by any reasonable definition, in the domain of military strategy. Between the world wars, both the Army and Navy had War Plans Divisions, they produced a variety of named war plans, and the Army and Naval War Colleges studied and contributed to war planning. After World War II, the emphasis on named war plans slowly but steadily decreased as war planning efforts turned to the Single Integrated Operational Plan (SIOP) for general nuclear war. By 2006, in the Joint Publications on Operations (3-0) and Planning (5-0), “war plans” appeared only in the glossaries under “strategic level of war.” By 2011, the term had disappeared altogether, and it has not returned in any meaningful way. Not coincidentally, war planning and war plans also disappeared from the curriculum at the war colleges, where the focus switched to policy-heavy national security, defense, and military strategies, and peacetime “campaign plans.”

If we want to assign blame for the deficit of military strategy, we should look there, at the war colleges. It wasn’t the Leavenworth heresy, it was the Carlisle dereliction.

A MODEST PLEA FOR WARTIME MILITARY STRATEGY

There are many good reasons for what happened, and a lot of good thoughtful work has come from taking a wider view of strategy. The point is to figure out what comes next for military strategy. I am picking on Carlisle because a wise colonel once pointed out that the best way to deal with a problem is with concentric circles starting at your own desk. My desk is smack in the middle of the Army War College.

The war colleges have shifted their focus away from military strategy, but we can rectify that overcorrection. The nation still requires military senior leaders who can guide the force in fighting and winning in wars and theaters of war. War colleges are still the ideal places to develop this capacity. We must spend more time reengaging military strategy in a serious and rigorous way, and that begins with asking questions and seeking answers.

The Army War College has the capacity—the people, time, and resources—to get that conversation going. That is the intent of these contributions. I might be the author, but the idea is to use WAR ROOM as an outlet for conversations among the faculty and students here, and as a springboard for pushing those conversations out to the rest of the U.S. Army and military. I hope you will comment, push back, and write your own contributions to move the conversation.

These reflections on military strategy will take on a number of approaches. Some will be about current concepts that are unhelpful or even harmful, and really ought to be discarded. Some will be about current ideas that can still be useful if we clarify or revise them. Others are about older theories of military strategy that have been discarded or forgotten but deserve another look as applicable today. And some, probably the most difficult, are suggestions for new approaches to military strategy.

The whole project—the conversations starting here and put out to the world for critique—is an attempt to provide some much-needed clarity and direction when it comes to military strategy. Contrary to too much conventional wisdom, we have a lot of room for improvement when it comes to wartime national and theater military strategy. To the degree we are good, it seems to come more from inertia than clear and deliberate study and practice. We are not bad. We can do better.

Fighting and winning wars is not done through euphemisms, neologisms, or technological fetishism. It is certainly not done through campaigning alone. We must put ourselves in the shoes of military commanders and staffs at the highest levels in war and think hard about what it is they have to do to be successful using violence in the pursuit of political aims. After all, the essence of military strategy is how we intend to win in a specific war or theater of war. For our military leaders, there is nothing more important than learning to do just that.

Thomas Bruscino is an Associate Professor in the Department of Military, Strategy, Planning and Operations at the U.S. Army War College and the Editor of the DUSTY SHELVES series.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

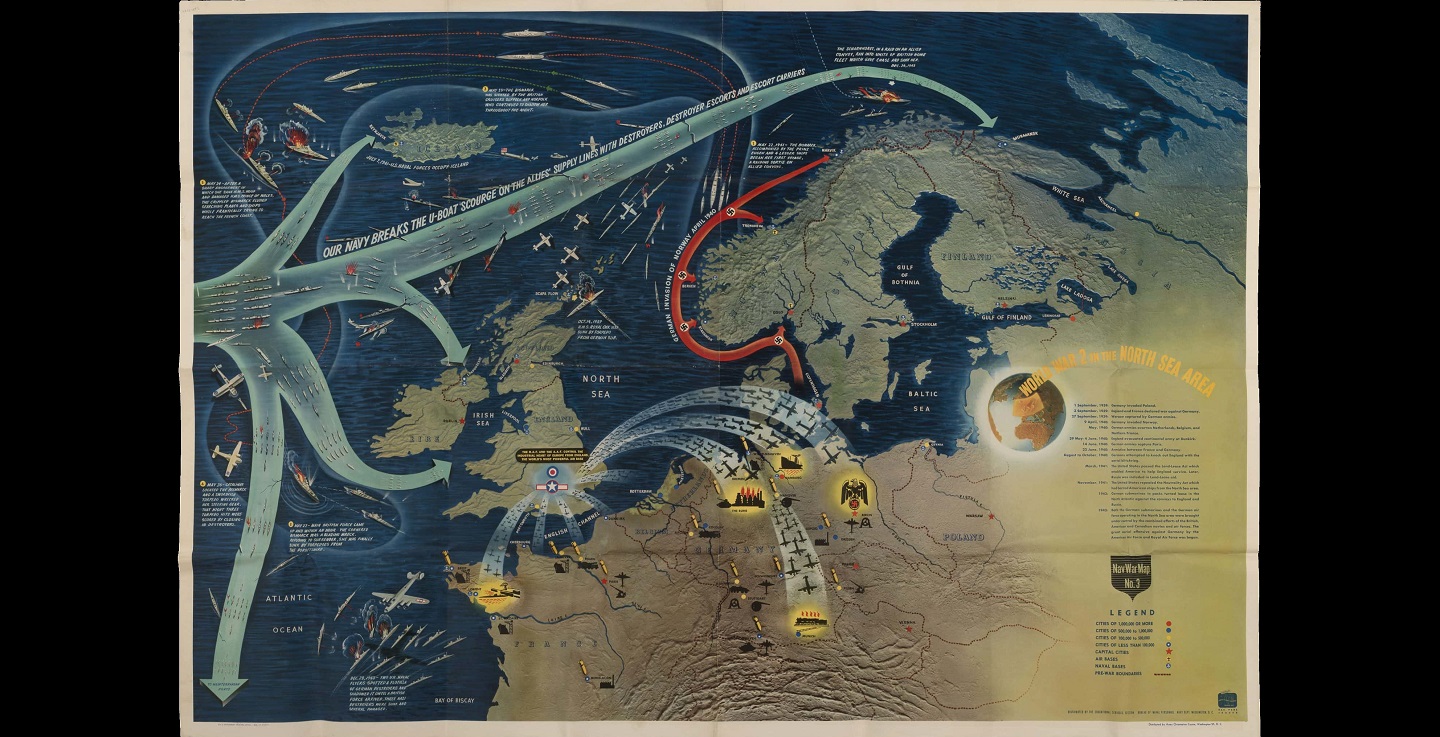

Photo Credit: U.S. Navy, Bureau of Naval Personnel World War 2 in the North Sea Area (detail), 1944