Operational art had become all-encompassing, because the Joint community called all war making at the national and theater level ‘campaigns.’

Ten years ago, Australian defense experts Justin Kelly and Michael Brennan published scathing critiques of American strategic thinking in Alien: How Operational Art Devoured Strategy and “The Leavenworth Heresy and the Perversion of Operational Art”. In those papers, both published by imprints of the United States military, the authors leveled their ire at a distorted and malignant version of American operational art which, in their view, had gobbled up strategy. The effect, maybe deliberate, was to separate and exclude policymakers from military activities.

The problem could be boiled down to a phrase in FM 100-5 Operations (1982): “The Operational Level of War involves planning and conducting campaigns.” For Kelly and Brennan, this was the heresy, because the design and execution of campaigns was rightly the exclusive and primary role of strategy.

In terms of the disappearance of military strategy, they had a point. Operational art had become all-encompassing, because the Joint community called all war making at the national and theater level “campaigns.” Even worse, ‘campaigns’ expanded outside the realm of armed conflict, and became the official form for peacetime activities of high-level commands: ‘Command Campaign Plans,’ ‘Joint Strategic Campaign Plan,’ ‘Global Campaign Plan.’

Since campaigns defined everything that militaries did in peace and war, operational art governed everything militaries did in peace and war. The Joint definition of operational art said so: “Operational art is the cognitive approach by commanders and staffs—supported by their skill, knowledge, experience, creativity, and judgment—to develop strategies, campaigns, and operations to organize and employ military forces by integrating ends, ways, and means.” These capacious definitions of campaigns and operational art left no room for strategy, whether that be military strategy in war or the various grand and national strategies of the policy realm.

Kelly and Brennan were on to something, but there were two major flaws in their argument. First, they were wrong about the motive for developing and teaching operational art within the Army and at Leavenworth. Few, if any, wanted to use operational art to exclude policymakers from military action. Rather, the study of operational art was meant to improve large unit military campaigns and operations. A closer look at U.S. Army doctrine leading up to 1982 shows that, if anything, operational art replaced corps, field army, and army group tactics, not higher headquarters strategy.

In fact, at the same time the Kelly and Brennan papers came out, a team at Leavenworth produced a more focused definition of operational art for Army Doctrine Publication 3-0 (2011): “The pursuit of strategic objectives, in whole or in part, through the arrangement of tactical actions in time, space, and purpose.” (Full disclosure: I was on that team.) At that time, while trying to think about operational art for counterinsurgency operations, the working hypothesis was that the levels of command that had to think operationally instead of tactically were lower, not higher.

That mistake connects to a second and larger flaw in their argument, which is that they lost sight of practical application. They connected neither strategy nor operational art to the actual people responsible for strategy and operational art, which left them with a limited view of the roles and responsibilities of higher military headquarters. That gap allowed them to buy into the premise that the military strategist’s primary or even sole role is planning campaigns.

That is not the case, and has not been for a long time, theoretically, doctrinally, or practically. True, strategy historically was generalship—the things that generals and admirals do, especially in command of campaigns. But around the turn of the twentieth century, theorists began to recognize that the roles and responsibilities of generals and admirals had expanded beyond just the campaign to preparing for and conducting the overall war effort or effort in a theater of war.

By the early 1940s, that trend was captured in doctrine, in the section on the War Department General Staff in the U.S. Army’s FM 100-15, Field Service Regulations, Larger Units. That headquarters had at least eight tasks:

- Determination of the enemy’s resources, combat strength, major dispositions, and capabilities.

- Decisions upon and preparation of broad basic plans of campaign.

- Determination of the organization and training required for the contemplated operations.

- Determination of requirements, and allocation and distribution of means.

- Accurate and clear delimitation of the responsibilities of major subordinate agencies.

- Approval or modification of plans and estimates submitted by subordinates.

- Coordination of the activities of the field forces.

- Attainment and maintenance of high morale, and combat and logistical efficiency.

The same manual had a section on theater commands that identified similar responsibilities. Even back then, campaigns were just one part of strategy.

The World War II example is illustrative. In that war, a wide variety of people had responsibility for elements of military strategy. President Franklin Roosevelt, Secretary of War Henry Stimson, chairman of the de facto Joint Chiefs Admiral William Leahy, Chief of Staff of the Army General George C. Marshall, Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Ernest King, head of Army Ground Forces General Lesley McNair, head of Army Service Forces General Brehon Somervell, head of Army Air Forces General Hap Arnold, Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower, among many others, had strategic responsibilities. But their tasks, responsibilities, and dilemmas in winning the war differed, and their approaches to meeting those tasks, responsibilities, and dilemmas had to differ too. All the while, almost none of them had to design and conduct campaigns. For the one who did direct campaigns, Eisenhower, that was nowhere near all that he did.

Operational art did not steal the campaign from strategy. Strategy stopped focusing on just the campaigns. Operational art helped fill that gap.

Senior military professionals knew that they were responsible for strategy, so as strategy grew and morphed, they followed.

THE CARLISLE DERELICTION

But that is not the whole story. If Brennan and Kelly correctly saw a problem—that military strategy seemed to have been replaced by campaigning—but misidentified the cause—operational art—then what was the real cause?

The simple answer is that strategy kept growing. What had once been the domain of generals and admirals in war expanded and took on new meanings. The Second World War, the so-called Cold “War,” nuclear weapons, and the exporting of strategic terminology to the private realm led to strategy metastasizing into its current form, as a catch-all for all thinking about policy, diplomacy, economics, operations, ideology, decision making, plans, positions, perspectives, patterns, ploys, long term advantages, ways of thinking, and so on. Strategy became the stuff of policymakers, businesses, sports teams, video games, financial planning, grocery shopping, and pretty much everything else.

Senior military professionals knew that they were responsible for strategy, so as strategy grew and morphed, they followed. They bought into the idea that strategy meant everything from policy to grocery shopping, so they had to study strategy in all of those forms. Military strategy, how to fight and win wars, became just one topic among many. Even at places where war-making was supposed to have pride of place, military strategy got drowned out by all of the noise.

The net result was that we stopped studying military strategy in any depth, and it was replaced by campaigns-as-wars. Here is a more practical illustration: war planning and war plans are, by any reasonable definition, in the domain of military strategy. Between the world wars, both the Army and Navy had War Plans Divisions, they produced a variety of named war plans, and the Army and Naval War Colleges studied and contributed to war planning. After World War II, the emphasis on named war plans slowly but steadily decreased as war planning efforts turned to the Single Integrated Operational Plan (SIOP) for general nuclear war. By 2006, in the Joint Publications on Operations (3-0) and Planning (5-0), “war plans” appeared only in the glossaries under “strategic level of war.” By 2011, the term had disappeared altogether, and it has not returned in any meaningful way. Not coincidentally, war planning and war plans also disappeared from the curriculum at the war colleges, where the focus switched to policy-heavy national security, defense, and military strategies, and peacetime “campaign plans.”

If we want to assign blame for the deficit of military strategy, we should look there, at the war colleges. It wasn’t the Leavenworth heresy, it was the Carlisle dereliction.

A MODEST PLEA FOR WARTIME MILITARY STRATEGY

There are many good reasons for what happened, and a lot of good thoughtful work has come from taking a wider view of strategy. The point is to figure out what comes next for military strategy. I am picking on Carlisle because a wise colonel once pointed out that the best way to deal with a problem is with concentric circles starting at your own desk. My desk is smack in the middle of the Army War College.

The war colleges have shifted their focus away from military strategy, but we can rectify that overcorrection. The nation still requires military senior leaders who can guide the force in fighting and winning in wars and theaters of war. War colleges are still the ideal places to develop this capacity. We must spend more time reengaging military strategy in a serious and rigorous way, and that begins with asking questions and seeking answers.

The Army War College has the capacity—the people, time, and resources—to get that conversation going. That is the intent of these contributions. I might be the author, but the idea is to use WAR ROOM as an outlet for conversations among the faculty and students here, and as a springboard for pushing those conversations out to the rest of the U.S. Army and military. I hope you will comment, push back, and write your own contributions to move the conversation.

These reflections on military strategy will take on a number of approaches. Some will be about current concepts that are unhelpful or even harmful, and really ought to be discarded. Some will be about current ideas that can still be useful if we clarify or revise them. Others are about older theories of military strategy that have been discarded or forgotten but deserve another look as applicable today. And some, probably the most difficult, are suggestions for new approaches to military strategy.

The whole project—the conversations starting here and put out to the world for critique—is an attempt to provide some much-needed clarity and direction when it comes to military strategy. Contrary to too much conventional wisdom, we have a lot of room for improvement when it comes to wartime national and theater military strategy. To the degree we are good, it seems to come more from inertia than clear and deliberate study and practice. We are not bad. We can do better.

Fighting and winning wars is not done through euphemisms, neologisms, or technological fetishism. It is certainly not done through campaigning alone. We must put ourselves in the shoes of military commanders and staffs at the highest levels in war and think hard about what it is they have to do to be successful using violence in the pursuit of political aims. After all, the essence of military strategy is how we intend to win in a specific war or theater of war. For our military leaders, there is nothing more important than learning to do just that.

Thomas Bruscino is an Associate Professor in the Department of Military, Strategy, Planning and Operations at the U.S. Army War College and the Editor of the DUSTY SHELVES series.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

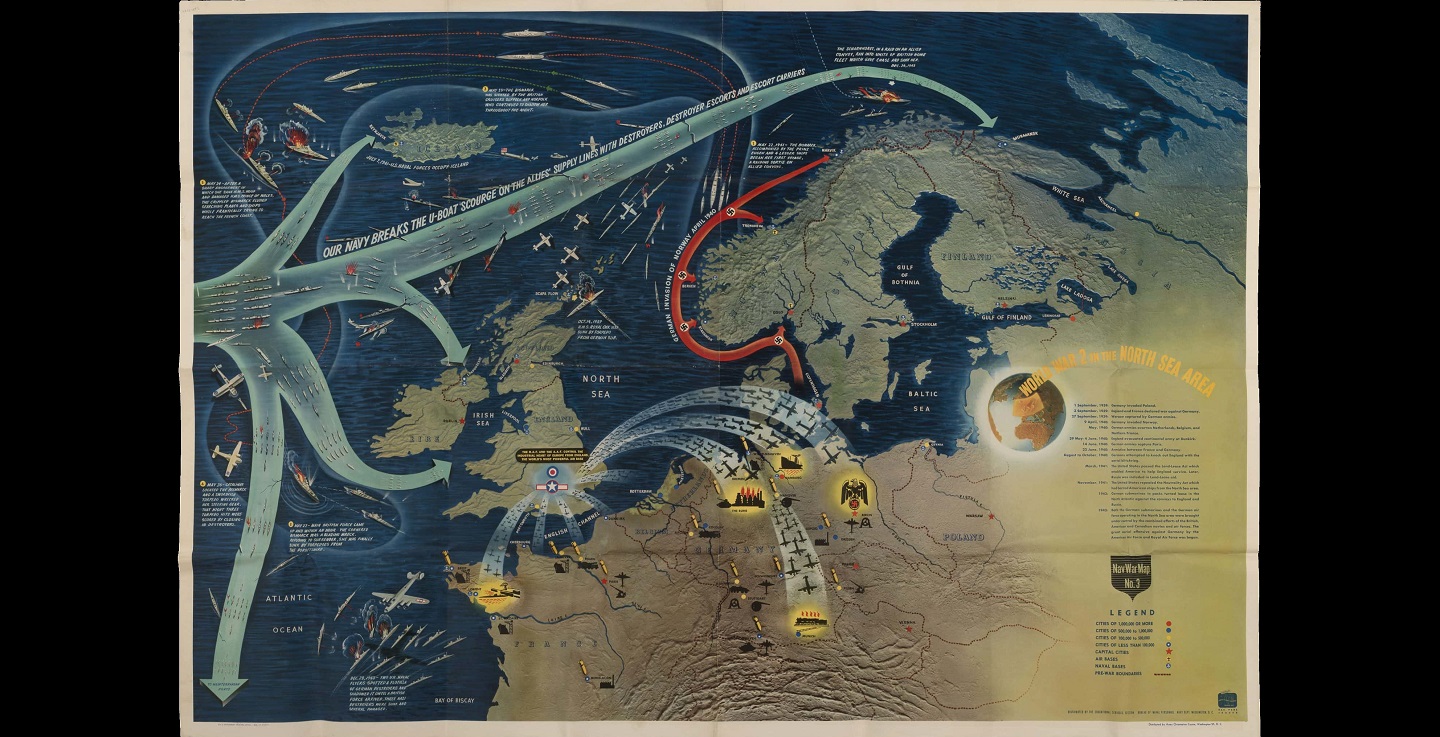

Photo Credit: U.S. Navy, Bureau of Naval Personnel World War 2 in the North Sea Area (detail), 1944

There are three strategy applications: Force Employment Strategy; Force Administration Strategy; and Force Design and Force Planning Strategy. This paper deals with an anomaly in force employment strategy – the boundary between the Strategic Level and Campaign Level.

My first major observation is that POLICY ( a largely political activity) comes before STRATEGY ( a COORDINATED ALL GOVERNMENT ACTIVITY). Neither feature is taught well in war college residence programs and the larger more diverse “Distance Learning” Programs are rarely exploited as an outlet.

My Second Observation is that the COCOM’s employ forces – but the services administer forces under Goldwater -Nichols but the COCOMS are not organized for the All Government Coordination of Foreign Policy. SERVICES DO NOT EMPLOY FORCES.

My third Observation is that the lessons of history on this topic before 1986 don not apply well in the Goldwater-Nichols Era.

Nicely done, Tom. I love it. And I’m a believer, as the whiteboard on my office door last week said, “It’s ok to study the actual conduct of war. We’re on scholarship for that.”

I’m surprised a phrase I learned from your office whiteboard didn’t make it into this piece: “Our problem is everything is fair game in strategy except fighting. (Because we associate fighting with tactics, and the only thing we are sure isn’t strategy is tactics.)”

More seriously, from a curriculum standpoint, if the US students conducted a deep review and exercise to rewrite a numbered OPLAN during the course, considering it would be done in a classified setting, we’d need to think through what that means for our international fellows and what they do during that time. To make it worth it, you probably need 3 weeks. We could figure it out, but something to consider. Additionally, the faculty discussion/debate to figure out what to cut would be exciting…leading the change effort on that one would take a master of strategic leader competencies.

Mr. O’Brasky,

Leaving aside the other stuff for now, and going to your comment about pre-Goldwater Nichols history, let me revise a paragraph from above.

“The Gulf War example is illustrative. In that war, a wide variety of people had responsibility for elements of military strategy. President George H.W. Bush, Secretary of Defense Richard Cheney, National Security Advisor Brent Scowcroft, chairman of the Joint Chiefs General Colin Powell, Chief of Staff of the Army General Carl Vuono, Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Frank Kelso, Chief of Staff of the Air Force General Merrill McPeak, Central Command commander General Norman Schwarzkopf, among many others, had strategic responsibilities. But their tasks, responsibilities, and dilemmas in winning the war differed, and their approaches to meeting those tasks, responsibilities, and dilemmas had to differ too. All the while, almost none of them had to design and conduct campaigns. For the one who did direct campaigns, Schwarzkopf, that was nowhere near all that he did.”

We could go through a similar drill for Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom, and pretty much any other conflict. Does putting these before and after Goldwater Nichols–which wasn’t that big of a reform, anyway–materially change the point?

We can and must learn from history about what military strategic leaders were up to during wars.

Thank you for the feedback!

Perhaps this is just an aside, but I wonder if it would be more fruitful to think of the levels of war as mental models thereby getting away from the debates of which echelon and when a particular level of war can be identified.

Furthermore, I am curious about how the concept (or fact, really, of fighting in) of multiple domains will complicate an understanding of operational-level warfare. I know it’s been defined in various ways, but I’ve always found it useful to think of operational warfare as the orchestration of tactical engagements to achieve non-linear success (i.e., the synergy part). TO see where I’m going with this, it is important to note that we find in FM 3-0 that the division is the first echelon capable of fighting in all domains at once. It is also considered the primary tactical unit in LSCO. The orchestration of BCT tactical engagements, along with functional or multifunctional brigades, across the domains can lead to non-linear success. It too is an orchestration of entities.

I really enjoyed the article and enjoy thinking about the conceptual implications of characterizing gradient of warfare.

Tom, Great effort on an important topic. Sure glad we hired you at SAMS and that you are now at Army War College and taking on major issues for war planning. I have one question: What do you think the last two decades of counter-insurgency warfare have done to the intellectual focus of military thought in the US? In the inter-war years we did, indeed, have all those colored plans but if you looked at the curriculum at the Naval War College and fleet exercise you had a good sense that “Orange” was at the heart of war preparations. The Army enjoyed no such strategic clarity until the wake-up call of France 1940. The Louisiana Maneuvers came a year later and it was quite clear whom the probable opponent would be and its was the Wehrmacht. The irony, of course, is that the Navy by that date was already involved in an undeclared war in North Atlantic against German submarines seeking to strangle Britain. Right now it seems to me that our strategic posture points toward major wars in Eurasia, but it remains unclear whether we are preparing for two major wars or one very large one. And that really does matter. Goldwater-Nikols was enacted in 1986 as Cold War tensions were declining. From 1989 to 2001 no single major threat drove defense planning and for most of the two decades since 2001 it has been counter-terror and counter-insurgency challenges which have been the drivers. Since 2014 one can argue that we have faced a much more complex strategic environment and complexity plays havoc with linear assumptions regarding future conflicts. Keep writing!

Dr. Bruscino,

Great article. I may have missed it but do you offer a definition of “military strategy” or “war strategy.” I think it might be difficult to define. Our combatant commanders develop regional strategy that goes beyond the military dimension of power and they (sometimes along with JTF Commanders) wield so many nonmilitary tools (if they have developed good regional and interagency relationships). The idea of military strategy gets a little fuzzier for me when you consider the reality of continuous competition below the level of war. And the likely candidates to conduct the counter campaigns are our Geographic Combatant Commanders. I know some are calling for increasing combatant command authorities to be able to counter adversarial “gray zone” campaigns that flirt with the threshold of open conflict. It seems as if they are executing regional strategy in support of national ends, not just military strategy, although you didn’t say they were, my understanding only.

Adam, Yes, my working definition for military strategy is: how we intend to win this war or in this theater of war.

In my view, Combatant Commanders do not do military strategy and they definitely do not campaign, unless they are in armed conflict and they have command of the (Combined) Joint Task Force.

In peacetime, or day-to-day, they do all that so-called competition stuff, but that is not campaigning and it is not military strategy either. It is really regional or theater military policy, in support of national policies.

As you might have gathered, I don’t think the National Security Strategy, National Defense Strategy, or National Military Strategy are “strategy” either. Those are all policies too.