Scientific knowledge is human knowledge and scientists are human beings. They are not gods, and science is not infallible. Yet, the general public often thinks of scientific claims as certain truths. They think that if something is not certain, it is not scientific and if it is not scientific, then any other non-scientific view is its equal. This misconception seems to be, at least in part, behind the general lack of understanding about the nature of scientific theories.

The Information Apocalypse has eaten away at the foundations of society – in our institutions, through trust in our professions, and in denigrating respect for the pronouncements of professionals and the opining of experts. We need a new construct for foundational trust and security, one not based on society’s past failures but on the concept of a new standard for interpersonal communication. The act of communication itself can serve to restore social norms and values if communication is built on plain talk, hard facts, and a healthy respect for the truth.

Apart from modern improvements in general communication norms (speed of transmission, access to information, and flattening of hierarchical pathways), one standard for accuracy in STEM (science, technology, engineering, math and medicine) communications remains constant – the validation of the concepts and approach of science. This process assumes a logical, empirical process of discovery and the assemblage of facts, which leads to the establishment of, findings, results, and interpretation. But even this broad validation of the scientific process is butting heads with institutions, professions, and individuals with bias, preconceptions, and opposing and perhaps contradictory, strong beliefs. Even this bedrock of modern societies is now being questioned at every turn.

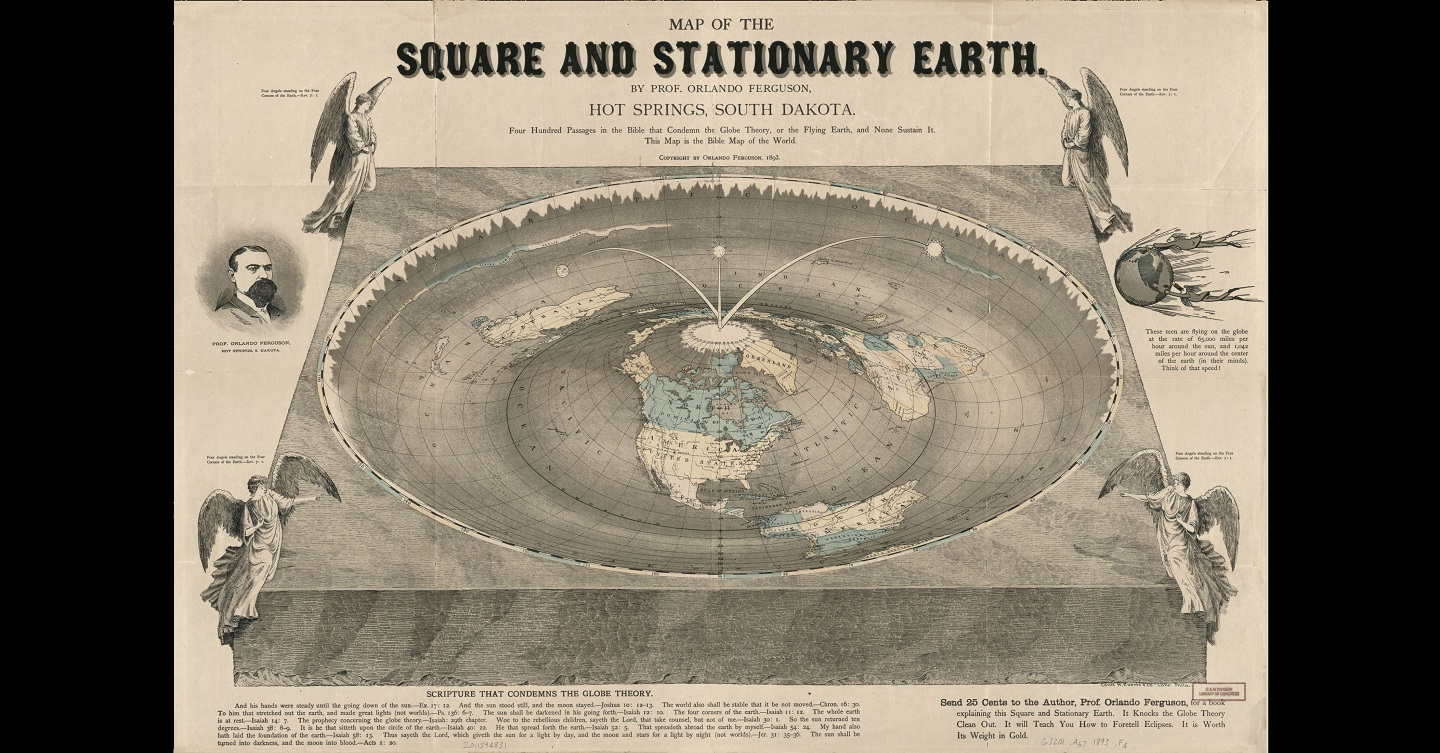

Of course, the veracity of science has been discussed, argued, and fought over since the claim that the earth was round ran headlong into those who believed it, no – knew – it to be flat. From the story of Adam and Even found in the book of Genesis to the theory of evolution, scientific inquiry and thought has been pitted against institutions – the church, the state, business, and media – as interests collide. Most recently we have seen several major conflicts in the arena of science versus anti-science. On one hand scientists claim that vaccines prevent disease. The opposition is led by the vociferous anti-vaxxer movement – whose adherents claim vaccines can cause disease, not prevent it, and cite dubious internet sources as proof of every side effect ranging from autism to cancer.

Yet a hallmark of modern society is respect for the facts of science and the processes of scientific discovery to inform policy and decision making. If the scientific process can be trusted, it is also clear that what counts as established science, in fact, changes, and that scientists are not infallible.

Sometimes, science has indeed caused harm, often unintentionally, but nevertheless with tragic results. The case of the drug Thalidomide is instructive. Thalidomide was marketed in the 1950s as a sedative and was favorably looked at as an alternative to barbiturates. But it was quickly criticized for causing nerve damage in some older patients. Then the tragedy of birth defects began. The drug is still in limited and controlled use, for therapeutic effects in treating leprosy, lupus and certain cancers. The science of the drug’s development was sound, but safety protocols were lacking, and the broad application of the drug was not only faulty, but negligent.

Another problem is that science (and its rhetorically close, but definitionally-opposite kin, pseudo-science) has at times been deliberately deployed in service of harmful ideologies or political programs. Examples include phrenology, the popular 19th century study of the contours of the skull, believing that certain bumps and bulges could reliably predict intelligence and character. The practice was discredited in the 20th century. Another 19th century pseudo-science was eugenics, a flawed concept that the human race could be improved through selective breeding out of ‘undesirable traits,’ such as epilepsy or criminal tendencies. It was most notable in the practices of Hitler’s cruel Third Reich medical experiments, as he sought to create a ‘master race.’

Today the continued development and potential for genetic modifications and editing to eliminate certain diseases continues to have both detractors and supporters, whether for religious or ethical reasons. In some fields the capabilities of science may appear to have exceeded the general public’s ability to accept results. Even debunking cannot convince all believers – for a minority, reality is of their own making and not even hard facts can make a dent in their beliefs. The process of communication continued to be of paramount importance, throughout the process of study, testing, results and potential application.

Science generally prevails when multiple independent studies, conducted in an impartial, empirical manner, reach the same conclusion. But then, “science” must be interpreted. One must then balance the facts versus ‘alternative’ facts and question whether other rationales (such as emotion, habit, or even faith) are preferable to prevailing scientific logic. Even if delusion appears more attractive and logic less comfortable, there is always an advantage to choosing logic. This advantage remains even if the science-based answer requires implementation of a course of action that is neither easy nor assured. There may also be a null result from scientific query or research. Not all scientific practices produce a positive result, a phenomenon that the public may be, if not unwilling, or unable, at least unused to seeing or accepting.

A different phenomenon is at work when science, even clearly established, is still perceived as questionable. That is partially the result of interpretation. We may not understand the science behind the creation of a vaccine, the chemical formula that creates clean fuels, or the specialized engineering design for a new drone, but people can and do question how that science is interpreted and communicated. For a host of reasons, scientists rarely communicate in unmediated ways with the general public. Rather, scientific knowledge is mediated—it is the administrator, the manager, the marketer, the politician, or the journalist, who may report, make claims and seek profitable application of scientific achievements and inventions, perhaps at times to the detriment of the end user, or the scientific community itself.

Science versus non-scientific methodologies is a massive and wide-ranging topic. This extends beyond medicine, technology, and invention to our perceptions of the natural world. We might look at the topic of global warming and climate change to understand how science and anti-science camps work to interpret the world and enact policy based on those interpretations. The non-believers refuse to believe that global warming is occurring. The believers fear for the future. One side cites the need for fossil fuels as reason to continue drilling, fracking, cutting and taking natural resources from the earth on a global scale – oil, gas, coal, trees, water. The believers want conservation, thoughtful awareness of consumption, a reduction in materialism, increased regulation of gas emissions, and more. It is a conflict destined to result in gridlock with neither side able or willing to learn from the other. Can science compromise? If we are talking hard facts and reasoned expectations, there is little to compromise on. In many cases there is one truth: for example, the planet is warming. But there are various viewpoints as to what to do about it and how.

Voices advocating for response to climate change are increasingly louder. That advocacy is also a call to action by the scientific community. Disasters, ranging from melting glaciers to rising seas, and severe health challenges such as COVID19 will increase. Without a vaccine and compliance with recommended guidelines, the pandemic continues to rage (against the mask). Having arrived on the scene, just as the Edelman 2020 study claimed that trust in all institutions was at an all-time low, the novel coronavirus strained at the bonds of credibility in every institution. False narratives and disinformation continue to spread, with outlandish claims such as: the virus will disappear on its own, a vaccine would be used to implant microchips in patients, or that some individuals who took part in vaccine trials have died. This is a typical pattern for propaganda, or disinformation – led by whispers of conspiracies and mistrust of government, even mistrust of experts and scientists.

The only antidote to this emerging pattern is one of factual communication and public engagement. The developmental process associated with the formation of theory, the science behind the research, the uses and access to data, it all has to be transparent and communicated in plain language that even non-scientists can grasp. According to branding and communications expert New York University Professor Jacqueline Strayer, an essential rule of effective (and credible) crisis response is TRANSPARENCY.

But to be convincing, the language of science must be based on a common denominator. Numerous scientific terms have different meanings to the professional and to the layperson. What scientists mean when they use words like “theory” is not the same as its colloquial usage. Colloquially, we use theory to denote something that may or may not be true—it is a guess, an unsubstantiated claim. But for scientists, a theory typically is denoted as such because of a high degree of certainty that it is correct. A scientific theory is so well established that new evidence is unlikely to change it. For scientists, fact, hypothesis, law, and theory have specific meanings, which may differ significantly from how they are used by lay people. Linguistic precision is important because otherwise interpretations may be varied and driven by competing agendas or emotion.

We may expect that the drive forward to a new construct for foundational trust and security will be first led by the business sector. An Edelman special report on brand trust, released in June, 2020, reveals that now, more than ever, people trust brands to solve problems, communicate clearly, and advocate for change. Brand trust has risen along with the issue of individual vulnerability – health, privacy, and financial stability. Over 81 percent of those surveyed said they trust reliable brands to lead the way ahead for society. This is true for both consumers and for private sector employees and companies with a focus on corporate responsibility. There are high expectations for business to act, and a great measure of reliance on CEOs to do the right thing. Another Edelman report focused primarily on response to the pandemic, noted that in eight out of ten countries surveyed, individuals responded that, “My employer is better prepared than my government.”

The basics of communication have much to teach about how to restore trust in institutions, professions, and people. Continuous and open communication is key – with a goal of transparency – plain talk, zero blame, no politicization, and even humility can go a long way to restoring trust. Facts, rational and reasoned discourse, and scientifically proven courses of action will lead to increased trust in public institutions and decision making for the greater good.

Mari Eder is a Featured Contributor to WAR ROOM. She is a retired major general in the U.S. Army and an expert in public relations and strategic communication. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

Photo Description: MAP OF THE SQUARE AND STATIONARY EARTH. Captioned: “Four Hundred Passages in the Bible that Condemn the Globe Theory, or the Flying Earth, and Nones Sustain It. This Map is the Bible Map of the World.” 1893

Photo Credit: Orlando Ferguson and L.H. Everts & Co. via the U.S. Library of Congress Geography and Map Division Washington, D.C. 20540-4650

WAR ROOM releases by Mari Eder:

- IN PLAIN SIGHT – THE INSECURE LEADER – A BULLY OF A BOSS

- DID WOMEN JUST NOT EXIST?

- AFTER THE INFO-APOCALYPSE (AA) (PART 1) – TECH THE UNTAMED

- LINCOLN AS STRATEGIST: EXERCISING THE ELEMENTS OF NATIONAL POWER

- THE INFORMATION APOCALYPSE PART X: THE ROAD AHEAD

- THE INFORMATION APOCALYPSE PART VIII: CIVICS LESSONS

- THE INFORMATION APOCALYPSE, PART VII: COMPETENCE AND ETHICS

- THE INFORMATION APOCALYPSE, PART VI: PARANOIA AND PRIVACY

- THE INFORMATION APOCALYPSE, PART V: THE FOURTH ESTATE

- THE INFORMATION APOCALYPSE, PART IV: INTELLIGENCE SECRETS OF SUCCESS

With regard to the matters presented by our author above, for example, as suggested in her concluding paragraph here:

“The basics of communication have much to teach about how to restore trust in institutions, professions, and people. Continuous and open communication is key – with a goal of transparency – plain talk, zero blame, no politicization, and even humility can go a long way to restoring trust. Facts, rational and reasoned discourse, and scientifically proven courses of action will lead to increased trust in public institutions and decision making for the greater good.”

With regard to these such matters, consider what might be (?) the alternative argument offered below:

“In 2014, following the Russian invasion of Crimea, The Washington Post published the results of a poll that asked Americans about whether the United States should intervene militarily in Ukraine. Only one in six could identify Ukraine on a map; the median response was off by about 1,800 miles. But this lack of knowledge did not stop people from expressing pointed views. In fact, the respondents favored intervention in direct proportion to their ignorance. Put another way, the people who thought Ukraine was located in Latin America or Australia were the most enthusiastic about using military force there.

The following year, Public Policy Polling asked a broad sample of Democratic and Republican primary voters whether they would support bombing Agrabah. Nearly a third of Republican respondents said they would, versus 13 percent who opposed the idea. Democratic preferences were roughly reversed; 36 percent were opposed, and 19 percent were in favor. Agrabah doesn’t exist. It’s the fictional country in the 1992 Disney film Aladdin. Liberals crowed that the poll showed Republicans’ aggressive tendencies. Conservatives countered that it showed Democrats’ reflexive pacifism. Experts in national security couldn’t fail to notice that 43 percent of Republicans and 55 percent of Democrats polled had an actual, defined view on bombing a place in a cartoon.

Increasingly, incidents like this are the norm rather than the exception. It’s not just that people don’t know a lot about science or politics or geography. They don’t, but that’s an old problem. The bigger concern today is that Americans have reached a point where ignorance-at least regarding what is generally considered established knowledge in public policy-is seen as an actual virtue. To reject the advice of experts is to assert autonomy, a way for Americans to demonstrate their independence from nefarious elites-and insulate their increasingly fragile egos from ever being told they’re wrong.”

(See the Mar/Apr 2017 issue of Foreign Affairs and, therein, the article “How America Lost Faith in Expertise: And Why That’s a Giant Problem” by Tom Nichols.)

Question:

From the point-of-view presented by the excerpt from the Foreign Affairs article noted above, might we say that “trust” (as per the author of our “War Room Blog” article here) is not the issue? Rather, the issue would seem to be:

a. The “status” of a particular group or “class” (that of the so-called “common man”) and

b. The perceived threat posed to same by the so-called “elite” group or “class?”

(Thus the “enemy,” accordingly from this perspective, being perceived of — not as China, Russia, Iran, N. Korea, the Islamists, etc. — but, rather, as the world’s scientists, its businessmen, its professionals and/or other “elites” and “experts?”)

From this such perspective, of course, the “cure” is not more, simpler and/or better (extremely humbling to the “common man?”) information, knowledge, etc., but, rather, a champion to promote, protect and/or restore the status of the “common man” — a role for which Trump, and his agenda, made something of a “good fit?”

Here is the concluding paragraph from our article above:

“The basics of communication have much to teach about how to restore trust in institutions, professions, and people. Continuous and open communication is key – with a goal of transparency – plain talk, zero blame, no politicization, and even humility can go a long way to restoring trust. Facts, rational and reasoned discourse, and scientifically proven courses of action will lead to increased trust in public institutions and decision making for the greater good.”

Question:

If the “facts, rational and reasoned discourse, and scientifically proven courses of action” all require that — in the name of such things as “national security” — you must give up or significantly alter your time-honored way of life, your time-honored way of governance, your time-honored values and/or, shall we say, your “status” derived from same:

“All in all, the 1980s and 1990s were a Hayekian moment, when his once untimely liberalism came to be seen as timely. The intensification of market competition, internally and within each nation, created a more innovative and dynamic brand of capitalism. That in turn gave rise to a new chorus of laments that, as we have seen, have recurred since the eighteenth century: Community was breaking down; traditional ways of life were being destroyed; identities were thrown into question; solidarity was being undermined; egoism unleashed; wealth made conspicuous amid new inequality; philistinism was triumphant.” (Also from the book “The Mind and the Market: Capitalism in Western Thought,” in this case, from the section therein on Friedrich Hayek)

Then, in such circumstances as these, would you:

a. Be interested in listening to, supporting and/or complying with such accurate and truthful facts, rational, etc.? Or would you, instead,

b. Be more interested in listing to, supporting and complying with what might be called “alternative” facts, reasoning, etc.; in this case, designed to better provide for your own, rather than the nation as a whole’s, “interests?”

(Such things as “trust,” from this perspective of course, only being able to be restored by addressing the “ills” noted in “The Mind and the Market: Capitalism in Western Thought” item I provide above? A course of action which, in today’s hyper-competitive world, would only tend to compromise a nation’s security? Thus, the dilemma?)