Dennis Showalter In Memoriam

In the waning days of 2019, word passed among military historians quickly: one of the giants in the field, Dr. Dennis Showalter, had died. Almost immediately, memories and tributes and reminiscences began to appear. The WAR ROOM editorial team reached out to some of those influenced by Dennis Showalter, personally and professionally, to reflect on his influence on their work and their teaching. His influence and impact on the field—and on those of us working in it—is unmistakable.

Frederick Schneid, Chair and Professor, Department of History, High Point University

Recently, I received word that the great military historian and my friend, Dennis Showalter, passed away. Friends and colleagues who are military historians need no introduction to Dennis. And many of my students had the chance to meet Dennis as a guest speaker at High Point University, or were the recipients of his wisdom through the lectures I gave on Prussian and German military history, which I often drew from his books and articles.

I first read some of Dennis’s work as an undergraduate, and became more familiar with it in graduate school. I still vividly recall reading his Tannenberg 1914, in tandem with Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s August 1914, as a PhD student. The late Gunther Rothenberg, my doctoral director, thought very highly of Dennis, and introduced me to him. We corresponded by mail (at least in the days before email), and I first met him at a Society for Military History conference prior to my appointment at High Point University. At the meeting I asked Dennis for advice on balancing teaching, research and writing at a small, liberal arts university. Since he was a long-time faculty member at Colorado College, which is a similar institution, and while there he established an international reputation, I wanted his counsel. I will never forget his reply, and have repeated it frequently to young colleagues who ask the same question. Dennis said, “Rick, a page a day is a book a year.” I have tried to follow his precept.

Dennis was the first historian I invited to participate in the inaugural Gunther E. Rothenberg Seminar in Military History in 2006. He did not disappoint. He returned a decade later, and was as insightful and brilliant as ever. We spoke several times a year about life and work. In conversation, presentations and his written work, Dennis could be counted on to make incredibly amusing and sharp analogies. In one such discussion about the historian’s craft he remarked, “While we celebrate the Mozarts, we should honor the Salieris,” referring not to the characters portrayed in the movie Amadeus, but the actual historical figures. Dennis explained that it was the “Salieris” who contributed the day to day body of work who often went unnoticed, but who created the corpus upon which the Mozarts built. I have pondered his words for years. Of course, Dennis himself was a “Mozart.” Although he had no graduate students per se, he was a mentor to a generation of military historians. He was a titan, a friend, and will be greatly missed.

Cameron Zinsou, PhD Candidate, Department of History, Mississippi State University

We’ve lost a colossus in the field in Dr. Dennis Showalter. I was fortunate enough to speak, correspond, and briefly work with him over the past decade. He was without a doubt the most generous and kind scholar I have ever encountered. He told me at the annual Society for Military History Conference in Kansas City in 2014, “I’m as good as I ever was, just not as often as I used to be.” Dr. Showalter was cognizant of the toll of time and its inexorable progress. It’s something that always stuck with me. Sharing that exposed moment with him fostered a level of empathy that I continue to try to share with my colleagues in the profession.

Dr. Showalter graciously served as the commentator on a panel I organized in 2015 at the SMH in Montgomery. That I was giddy with excitement at having one of the pillars of the profession agree to comment on a second-year PhD student’s paper was an understatement. I sat in awe of his command of seemingly every aspect of history. Though I didn’t know him as long as some historians I felt his influence through the books of his I read and the ways in which his words continue to shape how we think and write about military history. More importantly, Dr. Showalter served as an example of how to be better and kinder to each other. We have no better example to follow than him. Thank you.

Thomas Bruscino, Associate Professor of History, Department of Military Planning, Strategy, and Operations, US Army War College

Some twenty years ago now, young graduate students were patting themselves on the back for being practitioners of the “new military history,” which had finally gotten away from the tired and distasteful stories of the fighting side of war. I was one of those students, and I had the feeling of being at the leading edge of something new.

Then I ran across a short article called “A Modest Plea for Drums and Trumpets.” Military historians, the author offered, “generally agree in their dislike for studying armies as military instruments. Operational history, the detailed analysis of who did what, where, and to whom, is even less highly regarded.” Instead they studied “military systems in the context of the social, political, and intellectual structures of which they are a part.” That was all good as far as it went, but the outcomes of wars were important to all history, and those outcomes could not be explained by systems and structures alone. Battle history still mattered.

The article came out in 1975. Not only was the “new military history” not new, one of the best correctives to its overreach had been published two years before I was born. Lesson learned. The author of the article, of course, was Dennis Showalter. I had not met the man, and I would never take a class he taught, but I was already his student.

I was in good company. He taught at undergraduate Colorado College, and so far as I know never served as the primary director for any doctoral student. And yet there are dozens, scores, maybe even hundreds who would consider him a mentor. A group of such distinguished military historians even put together a Festschrift for him—a book of original academic essays in his honor. Such tributes are usually made by former graduate students, but Showalter got one anyway.

The reason why can perhaps be found in that “Modest Plea” article. It was not that Showalter was uncontentious—he once wrote an article titled “Even Generals Wet Their Pants”—it was that even his most strident arguments came from an oceanic reservoir of intellectual curiosity. Getting battle history right was “painstaking, frustrating labor,” he wrote. “But the labor is necessary. Its primary expression may be in footnotes to studies of armies in society. But the footnotes are necessary. When a Roman general was awarded a triumph, a slave rode in his chariot to remind the hero that for all the cheers, the praise, and the laurel wreaths, he was still nothing but a man.” In case the point is lost, Showalter was the slave in this scenario. He wanted better answers, and had the supreme humility to love just being a part of getting there.

That incredible mix of curiosity, brilliance, and humility was on display in every interaction I ever had with him. Like so many others, the first time I met him in person was as a graduate student in 2005, when he attended a panel I was on with other graduate students at an academic conference. I sat there fairly terrified, trying to imagine what he could ever get from me. Showalter had forgotten more about our topics than we could hope to know, and yet there he was, larger than life, fully engaged, even asking questions in that deep rumbly voice of his. We left that panel walking on air. I saw it many times after—Dennis Showalter is here, in our panel. It never got old.

I got to know him personally later—I swear this is true—while riding on armored buses around Israel. We were there as part of a fellowship to study terrorism. Almost all of the participants were junior college professors from a variety of fields that were not history—political science, sociology, criminal justice, etc. Academic fame doesn’t travel far, and as giddy as I was to be in the same program with Dennis Showalter, I was surprised that the rest of the fellows were wondering who this old guy was and what he was doing there. Dennis could not have cared less. Of course a 71-year distinguished scholar should travel halfway around the world with strangers to trudge around Israel visiting military camps and prisons for terrorists.

I shamelessly took advantage of his relative anonymity to sit next to him and talk on the bus rides up to the Lebanese border or to Jerusalem and the West Bank. I can’t really think of another word: it was so much fun to engage with Dennis. He would get tired on some of those long days, but he never got tired of the delight in the give and take of ideas. It wasn’t just knowledge, although of course he had that in spades, it was the connections he would make, the way he would link some obscure reading he had come across years before to some other disparate concept that had come up in the conversation.

In retrospect, conversations with Showalter should have been terrifying, like trying to help Beethoven compose. Instead they were exciting. You wanted to play too. That was his gift, really. He would pull you in with his enthusiasm so that you forgot to have doubts or to worry what the great Dennis Showalter might think about you if you said something wrong. For crying out loud, after one of those conversations I sent him my master’s thesis. And he read it.

After Israel, I would see him at conferences and we would talk. He slowed down, as one does, and he could not go to quite as many panels. He had strong views about how his teaching career came to an end—a story for another time. But he never stopped being Dennis, and one of my last in person encounters with him was at a hotel bar in Louisville. He was sitting by himself. I was there with two good professor friends, not military historians, who had heard of him but never met him. We joined him at a table and got to talking. You know the rest: soon the old master had two more captivated students.

My very last interaction with him was a WAR ROOM one. This past fall, when I took on the Dusty Shelves series and sent out an email asking for contributors, of course I included Dennis. He wrote back that he would love to, but, and this was much to my delight, “I am committed to the limit right now.” He signed off that email “Apologetically, Dennis.”

Oh, Denny, you had nothing to be sorry about. As always, I was just so happy and blessed you responded at all. We all were.

Michael Neiberg, Chair of War Studies, US Army War College

I have a lot of wonderful memories of Dennis. My first trip to the western front was in a rented Peugeot with him and an old set of Michelin maps. What a way to experience it, with Dennis telling me stories of the veterans he had spoken with in the 1960s and picking out details I never would have seen without him.

I also remember a Society for Military History conference where Dennis was on the panel (the stage on which he shined the brightest). A young student, maybe even an undergrad, asked a simple question. As soon as she was done, a quite senior member of our profession just asked his question as if the student’s question was beneath the dignity of the panel. Dennis stopped him and said, “I don’t believe we have an answer to the previous question yet.”

Dennis was old school. He believed in debate as much as he did in being right, and he had a thousand ways to disagree with you without belittling, degrading, or name calling. He was part of the generation that made the field of military history more inclusive and more welcoming. He could be deeply conservative on some issues, but if you had the intellectual firepower, he was 100% behind you no matter who you were or whether you agreed with him or not.

Dennis gave me the courage to teach from a Post-It note instead of a lesson plan and to write on subjects outside my direct area of expertise. If Dylan can go electric, he once told me, you can write on any subject you want and don’t let anyone tell you differently. But above all he taught me how to be an academic: respect divergent viewpoints; welcome everyone into the club; and treat every student and colleague with the same kindness and respect.

Dennis did not much like the telephone, so I did not talk with him as much in the last few years as I would have liked. But every time I did, we’d talk first about family. Then he’d ask what I was working on and inevitably he knew the current state of the field better than I did. Dennis was not a sentimental man, but if you feel like doing something to honor him, I know he’d appreciate any contribution to your local Humane Society. Stray cats, smart creatures that they are, showed up on his door with regularity and he loved them.

The views expressed in this memoriam are those of the contributors and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, U.S. Army, or Department of Defense.

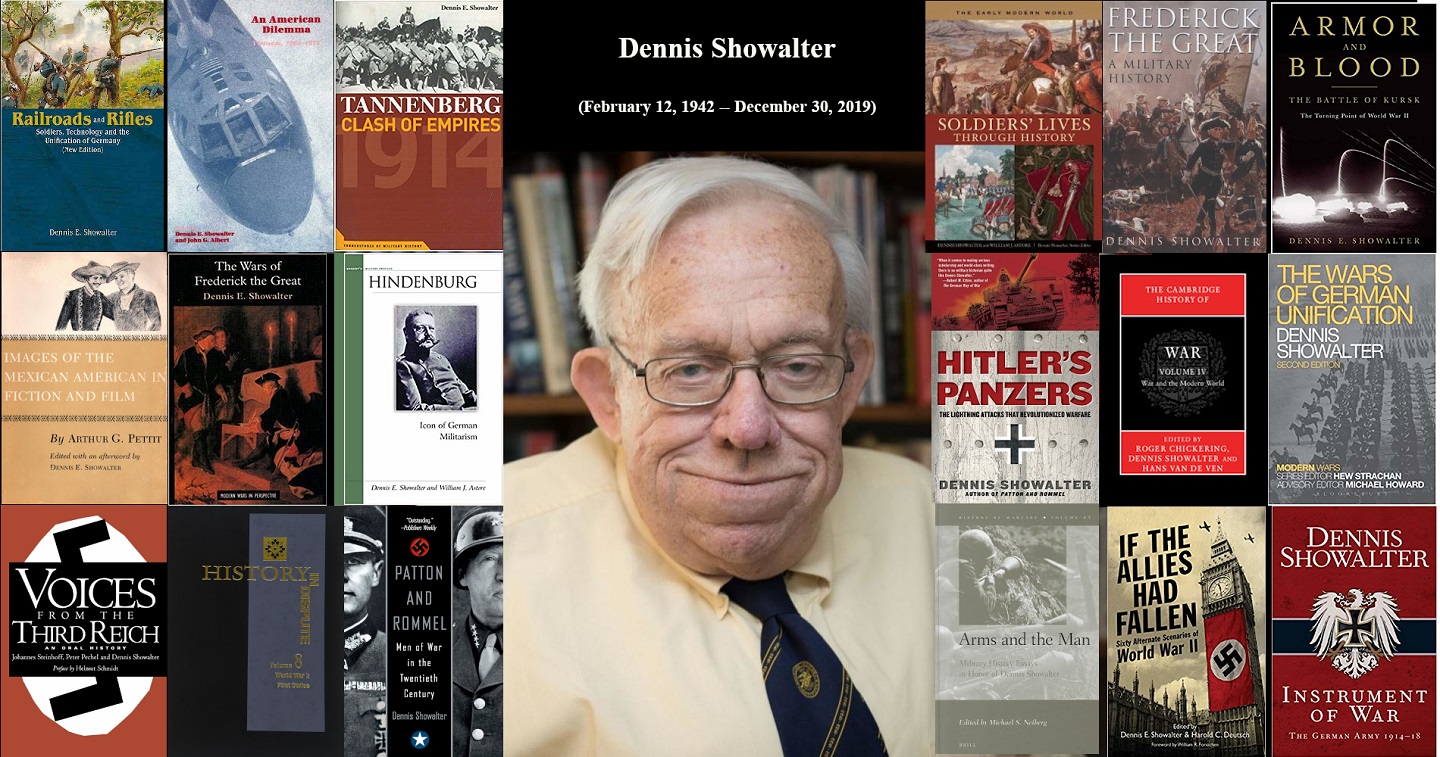

Photo Description: Dennis Showalter surrounded by some of his most well known works.

Photo Credit: Photo courtesy of the Pritzker Military Museum & Library