We need to encourage all officers to engage more directly in the generation of expert knowledge, and remove barriers to doing so based on rank or position.

I have never forgotten this incident.

I was a junior field-grade officer, and my boss — a senior flag officer — wanted to write an article but did not have the time to do it himself. He asked me to write something and gave me some ideas. I did some research and wrote the piece. My boss approved the finished product and said my name should appear on the by-line because of my contributions to the work. I submitted the co-authored article to the desired publication. The next day, the editor contacted me and asked that I remove my name; the editor felt that brand-name flag officers would never co-author works with someone so junior. The editor was concerned that readers would skip the piece. This was my first introduction to intellectual property in the Army. The editor’s advice stung, but I accepted it because the organizational culture dictated that everything in the organization was owned by the leader.

Early in my career, I learned that commanders were singularly responsible for the unit’s message. Subordinates seeking credit were in violation of the professional values of subordination and selfless service. In this light, removing my name from the article made sense. It seemed good for the organization. I will return to this incident below.

The question of ownership of ideas returned often during my ten years working in commander’s action groups, where I supported the development of over a dozen articles for publication with or on behalf of a senior officer or civilian. Sometimes I was credited as a co-author, sometimes I was acknowledged as a contributor in a footnote. Other times my name did not appear at all, especially when the work represented either the perspective of the command or the voice of the commander, regardless of whether my contribution justified co-authorship. Ghostwriting, “writing for another who is the presumed author.” The word “presumed” in that definition means that a major contributor to the composition of the piece was not listed as an author. In this sense, ghostwriting was a regular part of my duties to support the organization’s mission. My observations and the corroborating experiences of colleagues suggest that ghostwriting is a common practice in the military. Senior leaders routinely rely on junior officers to write articles, with varying standards for crediting the work of those officers. The implications are the subject of this essay.

Ghostwriting is a widespread yet controversial practice in organizations. In professional practices such as law, medicine, and the military, ghostwriting poses interesting ethical questions. At first glance, it seems dishonest to claim as one’s own the work of another, or to exclude another person from receiving due recognition for his or her contribution. Critics of ghostwriting charge that the resultant works may be deceptive and inauthentic, which is harmful to the profession. Critics have been particularly vocal in the field of medicine, where corporate ghostwriters publish studies under the names of reputable doctors. Critics charged that this introduces bias in research, raises concerns about financial conflicts of interest, and leads to overconsumption of pharmaceuticals. None of these improve trust in medicine.

In practice, however, ghostwriting is accepted without much scrutiny in many different contexts. For example, speechwriters compose orations for leaders, but speechwriters are rarely credited when a speech is entered into the historical record. Books, journal articles, and other written works often involve the work of ghostwriters for a variety of reasons, commercial and professional. In the publishing business, celebrities often use ghostwriters to write memoirs. This practice enjoys the dual advantage of ensuring higher-quality writing and enhancing name recognition to encourage better sales. Such relationships between ghostwriters and clients are established in U.S. law and perceived as legitimate. The high demands on military leaders often preclude them from doing much of their own writing. They may have the ideas and arguments, but they need someone with writing talent to package it together efficiently.

If we accept that military ghostwriting is common and has legitimate use, are there conditions when it becomes problematic? The opening of this piece illustrates two concerns: (1) denying recognition of co-authors for reasons of protocol, and (2) conferring false legitimacy to a written work. While that example involved an external editor, I have encountered similar concerns arising from within my own organizations when it came to co-authorship claims.

The first concern is about the meaning of authorship and its application in the military context. The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors applies a four-part authorship standard commonly used in publishing: (1) substantial contributions to concept or design of the work, (2) drafting and revising the work for content, (3) approval of final version, and (4) accountability for all aspects of the work. From my experiences, (1) and (2) are non-issues. The tensions arise in the latter two. I am not talking about when written works are prepared for commanders performing their official duties. The commander has final approval and is solely accountable. No debate there.

The problems surface in the murkier situations where officers (usually commanders) take credit for work unrelated to their duties. In such cases, ghostwritten articles benefit the credited officer as an individual more than the organization. Examples from my experience include what my colleagues called legacy pieces, articles ghostwritten for commanders to celebrate claimed accomplishments, either during or especially toward the conclusion of their tours. Sometimes commanders are substantial contributors to a work; at other times, work is left to the staff to prepare, submit, and publish with little or no commander involvement. After writing one such piece, I was dogged by questions over whose article it was — the commander’s or mine? And if it was mine, I might have written it differently.

This dilemma raises questions about proper work for officers. Army doctrine has codified what it means for officers to be military professionals, including developing and applying expert knowledge through the exercise of discretionary judgment. Ghostwritten works allow leaders to contribute to that expert knowledge base when they cannot devote the time to do all the writing themselves. But, ghostwriters who help their superiors in endeavors that fall outside of the organization’s mission or professional obligations probably should be applying their writing talents elsewhere. Also, ghostwriters cannot include ghostwritten materials on their resumes. Thus, if the principal denies proper co-authorship, that may constitute plagiarism.

Ghostwriters who help their superiors in endeavors that fall outside of the organization’s mission or professional obligations probably should be applying their writing talents elsewhere.

The second problem concerns the legitimacy of a work, and is even thornier. The culture of military publishing still places significant weight on the rank and position of authors. Several publications catering to the military list the ranks, whether active or retired, of their contributors. This reflects the assumption that greater rank of authors equates to greater value of their work. Aside from the obvious inaccuracy of this assumption, widespread ghostwriting may in fact undermine the legitimacy of otherwise valuable contributions from senior officers. If we assume initially that the general officer did not write the article, we more readily dismiss it. In this regard, transparency about the origin of written work is more effective.

If just one assumption sits at the foundation of all of the various manifestations of military culture, it may be that the individual must subsumed into the collective. “This is not about taking credit, this is about [insert organization name],” is one possible response to the gripes of uncredited military ghostwriters. This may be a legitimate point, but it should apply only in cases in which a work is not credited at all. Instead, ghostwriters are not only discouraged from taking credit for their work, but they are also asked to acquiesce in reassigning credit for the work to someone else.

The dishonesty and exploitation that motivates some military ghostwriting may increase problems arising from the military’s cultural characteristic of power distance, which researcher Geert Hofstede defines as “the degree to which the less powerful members of a society accept and expect that power is distributed unequally.” Thoughtful officers accustomed to assigning credit to superiors are likely to be reluctant to share independently their own experience and perspective. Over several tours working in combined, joint, and service-level headquarters, I have been involved in or witnessed several impressive efforts to develop theater strategies, security cooperation plans, organizational transformation efforts, or strategic communication campaigns. The officers involved in this work had valuable insights that might have benefitted other units and organizations. Typically, however, the involved officers declined the opportunity to share their insights. While lack of time to write was often a factor, some officers simply did not want the risk associated with having their names on a by-line. Others saw publishing as a self-serving act. One went simply said that he did not want the attention. In this view, defaulting to a ghostwriting role seems natural. Take care of what’s in the always-full inbox that the leader requests and avoid scrutiny.

This needs to change. We should do more to encourage independent writing, and treat accountability for one’s expertise as a positive — an avenue for officers to be knowledge entrepreneurs, getting ideas and solutions out to the rest of the profession. Military ghostwriting should only be accepted when a work is published without any authorial credits. In all other cases, authors who make substantial contributions should be credited. We need to encourage all officers to engage more directly in the generation of expert knowledge, and remove barriers to doing so based on rank or position. Quality, measured through demonstrated critical thinking, should be the primary standard for measuring a contribution.

Returning to incident I discussed at the beginning of this article, when my boss learned of the editor’s request to exclude me from the by-line, he directed the executive officer to send a friendly e-mail to the editor declining the opportunity to release the article through that publication. We then published the article elsewhere.

Tom Galvin is a retired U.S. Army Colonel and a member of the faculty of the U.S. Army War College. The views in this article are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army or U.S. Government.

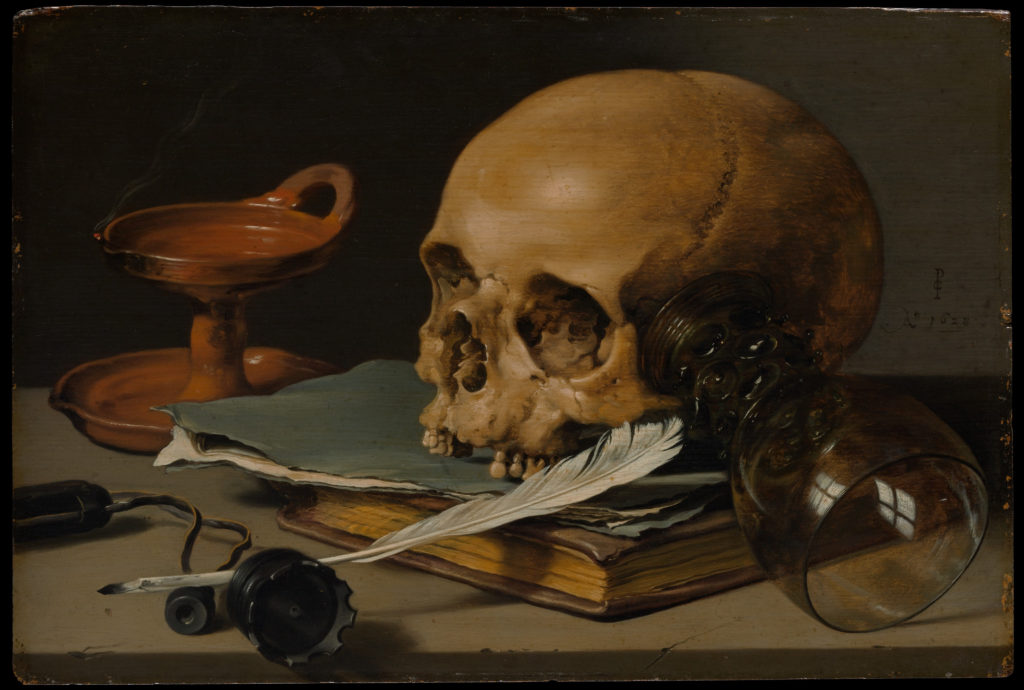

Image Credit: “Still Life with a Skull and Writing Quill” by Pieter Claesz (Dutch, Berchem? 1596/97–1660 Haarlem) / Rogers Fund, 1949 / New York Metropolitan Museum of Art