Although the U.S. Federal Reserve System is the only federal entity with a legal mandate to set monetary policy and manage inflation, inflation impacts every department and agency.

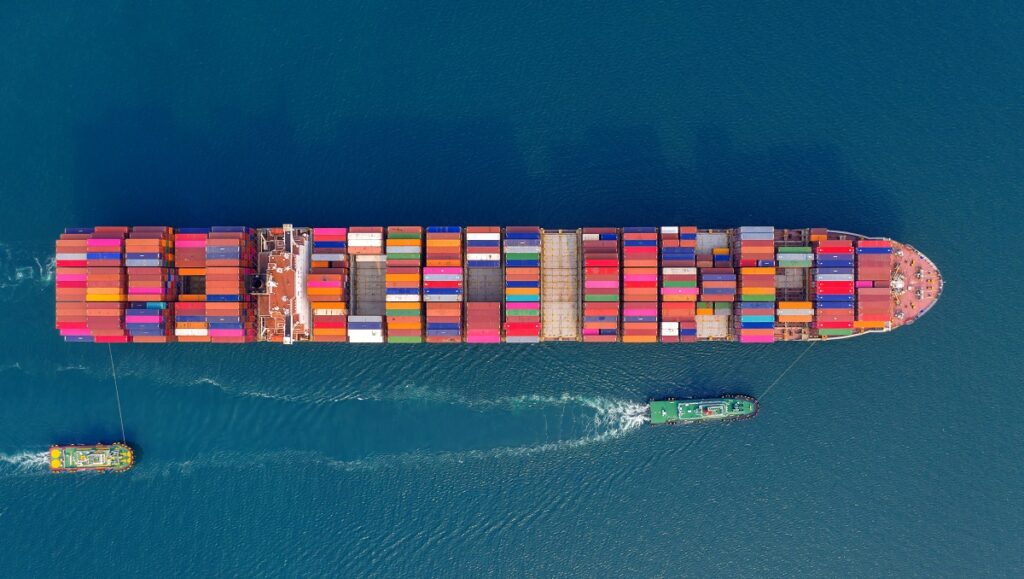

To endure and win conflicts of the future, U.S. national security requires monetary stability and economic resilience. The U.S. military must prepare to support civil authorities and deter foreign threats from stoking harmful inflation in the U.S. economy by disrupting supply chains. Temporary trade disruptions during the COVID-19 pandemic and the 2021 Colonial Pipeline ransomware attack contributed to the surge of inflation in the post-pandemic years. In January 2022, Chairman of the Federal Reserve Jerome Powell testified before Congress that the conventional monetary policy tools of the central bank were ineffective at countering inflation driven by supply-side shocks. Since 2023, however, U.S. and allied maritime security operations in the Red Sea and the Black Sea have contributed to lowered costs associated with threatened shipping lanes, despite not defeating the threats outright. Looking ahead, the U.S. military should prepare to manage and counter even worse supply-side inflationary shocks that might arise from competition or conflict with a great power adversary.

Persistent high inflation erodes the buying power of U.S. defense budgets for acquisitions, challenges the ability of military services to attract and retain qualified service members, and increases government borrowing costs associated with deficit spending typical in a major conflict. In early 2021, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell characterized surging inflation as not driven by enduring changes in demand but rather temporary supply-side shocks which raising the federal funds rate could not control.

Although the U.S. Federal Reserve System is the only federal entity with a legal mandate to set monetary policy and manage inflation, inflation impacts every department and agency. National security policy can intervene to combat the supply-side drivers of inflation that threaten national defense and the broader economic prosperity of the United States and its allies. In fact, the U.S. military has a long history of securing trade and commerce—which has the effect of lowering cost of imported and domestically produced consumer goods—predating the 1913 creation of the Federal Reserve System.

During the American Revolution, cut off from British imports, salt prices in the United States rose from 50 cents to 8 dollars per bushel. Salt was essential to food preservation techniques at the time and a critical input for New England’s fishing industry. Several states pursued measures to develop domestic salt supply chain including developing new suppliers like the Pennsylvania Salt Works in present-day New Jersey. Pennsylvania deployed the militia in 1777 to secure this essential industry amid threats from British and loyalist forces until the end of the war, when cheap salt imports would resume.

During the United States’ Quasi-War with the French First Republic, insurance premiums for shipping goods like molasses from the Caribbean climbed from 3-6 percent to up to 25 percent total value of cargoes in 1798. Molasses was essential to New England’s rum industry, and households in the colonial era commonly used rum to store wealth because it was in universal demand and did not spoil. The total value of merchandise imported to the United States declined by 9% from over $75 million in 1797 to $68.5 million during the peak of the threat in 1798. Product imports rebounded to a record $91 million by 1800, however, as U.S. Navy victories against French privateers in 1799 and 1800 contributed to reducing insurance rates and total shipping costs.

According to the International Monetary Fund, when shipping rates double, inflation typically increases by 0.7 percent in import destinations. While multiple inputs, including labor costs, drive shipping rates, insurance rates are the component of shipping costs most sensitive to the threat environment. Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, insurance rates—a significant component of total shipping cost and one highly sensitive to regional unrest—for ships traversing the Black Sea climbed from 0.025% of the value of shipped goods before the war to a high of approximately 5%. Winter wheat, an important Ukraine maritime export, saw prices surge from $374 per metric ton in January 2022 just before the invasion to $522 per metric ton in May 2022. Winter wheat prices began to steadily decline following highly successful Ukrainian unmanned surface vehicle strikes on the Russian vessels in October 2022; these successes forced the Russian Black Sea fleet to withdraw from areas near Ukraine’s coast and Crimea and operate instead from ports further from shipping lanes. As a result, by June 2023 winter wheat prices dropped below pre-war levels and inflation in the European Union—which peaked at 11.5 percent in October 2022, driven by food price inflation –began to subside in 2023 as food price increases slowed.

The military can also help on land to counter supply-side drivers of inflation.

Since the recent escalation of Houthi attacks on commercial shipping in the Red Sea, marine cargo insurance costs have increased from 0.03% to about 1% of the total value of goods for ships transiting the Suez Canal. Following the creation of a U.S. international task force under Operation Prosperity Guardian, maritime insurance rates shippers claim insurance rates initially began to level off, but increased again following a series of successful Houthi attacks on vessels in 2024. These increased insurance rates forced large container ships, which are disproportionately sensitive to increased insurance rates and quickly become prohibitively expensive to insure, to avoid the Suez Canal by traveling around the Cape of Good Hope at additional expense of fuel and several days of transit time. While Houthi attacks on Red Sea shipping indirectly impact the price of all goods which regularly transit the Suez Canal, the worst inflationary effects are hitting not the United States and its allies, but rather the developing countries around the Red Sea coastline—including Yemen itself—exacerbating already dire humanitarian conditions.

The military can also help on land to counter supply-side drivers of inflation. During the COVID-19 pandemic, disruptions at U.S. ports contributed to a surge in price inflation. The price of moving shipping containers increased, delivery times slowed, and shipping containers accumulated at major U.S. ports with inadequate drayage capacity. In response, the White House considered deploying the National Guard to alleviate port congestion, a mission that the Department of Defense can legally execute under the same Defense Support of Civil Authorities (DSCA) framework used for military assistance following hurricanes and other natural disasters. Although the White House ultimately decided against military deployment in favor of regulatory changes that allowed ports to spend money to expand throughput, the United Kingdom—which was experiencing similar supply chain disruptions during the COVID-19 pandemic—did use military servicemembers in such a capacity: Amid a fuel truck driver shortage, the British Army deployed domestically to deliver fuel to depleted distribution centers. Consumer price inflation is particularly sensitive to climbing fuel prices because fuel is a cost input to every food item delivered to grocery stores by truck in addition to retail fuel use for transportation needs. Although inflation in the United Kingdom did not immediately subside following the deployment, fuel prices in the United Kingdom did stabilize in the months before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which stoked European inflation again.

Monetary stability is essential for the U.S. military to execute its core mission: to fight and win the nation’s wars, and policymakers cannot ignore the growing impacts of inflation on defense resources and national security. Combatant commands must carefully consider emerging threats to trade flows and supply chains and how those threats might increase the prices of essential goods and services which eventually disrupt military campaigns. Although many factors contribute to inflation—including fiscal policy and spikes in demand—both recent and more distant history shows that the military is uniquely capable of addressing some of the supply chain disruptions which challenge the traditional tools of monetary policy to counter inflation. The Department of Defense needs to establish a coherent strategy and doctrine to measure the effectiveness of these interventions. In the future, campaign plans could even be designed around minimizing maritime insurance rates or maximizing container throughput at threatened ports. By preparing to deter inflation along with the growing military threat posed by great power adversaries, the U.S. military can ensure the economic resilience of our nation to prevail in the next global conflict.

Steve Speece is an active duty U.S. Army officer currently assigned to United States Strategic Command (USSTRATCOM) J2 as an Analytic Division Chief.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, U.S. Strategic Command, the Defense Intelligence Agency or the Department of Defense.

Photo Description: Aerial view of container cargo ship at sea.

Photo Credit: Image by tawatchai07 on Freepik