The nearly uncontested conquest of the town at the center of the novella is thanks in part to a collaborator in their midst, a prominent townsperson who had set the conditions that ensured a smooth entry for the invading force.

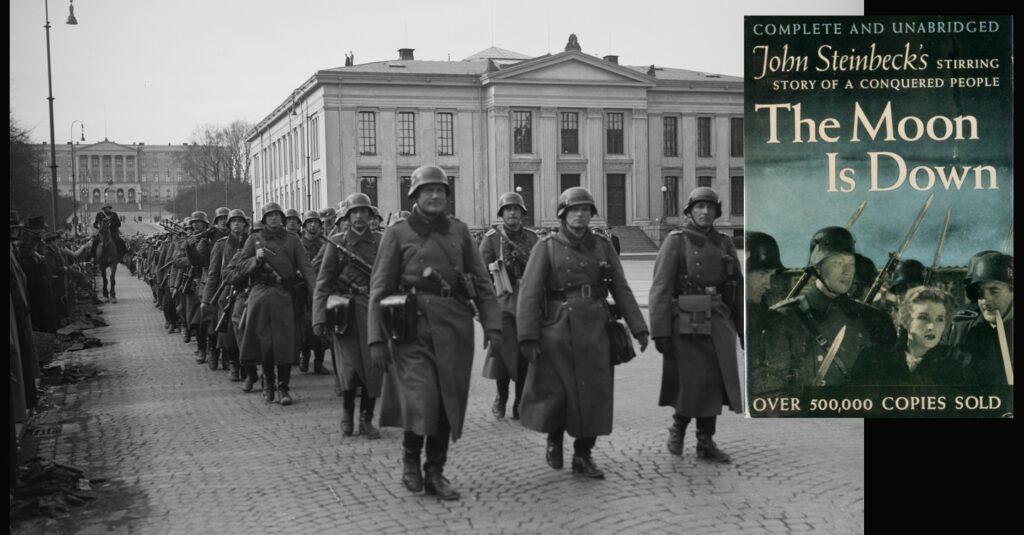

Most readers likely associate John Steinbeck with mandatory High School assignments—The Grapes of Wrath, or perhaps Of Mice and Men—and are not aware of his work during the Second World War. Steinbeck served as a war correspondent in England and in Italy, and much of his wartime writing (both fiction and nonfiction) was borne out of his own experiences and observations. One of his lesser known works is his short classic of resilience and civil resistance, The Moon is Down.

Published in 1942, The Moon is Down is set in an unnamed Northern European country, where an invader (with some very thinly veiled similarities to Nazi Germany) rapidly overcomes the people of a mining town and their miniscule local militia. The nearly uncontested conquest of the town at the center of the novella is thanks in part to a collaborator in their midst, a prominent townsperson who had set the conditions that ensured a smooth entry for the invading force. The book does not focus on the invasion however, and contains no battle scenes, but centers rather on how people cope with occupation, and the social dynamics at play within resistance movements.

Shaken by their rapid capitulation and immediate occupation, the townspeople do not know precisely how to interact with their initially benevolent invaders, and are vexed as to how to feel about the new status quo. The town is isolated from the rest of the country, and the local leaders grapple with what the appropriate behavior is for an occupied people. The commanding officer of the invading force, a Colonel Lanser, is obligated by his orders to administer the town through collaborating local authorities. As a result, the mayor is not removed, but remains the face of the local government as Colonel Lanser and his staff attempt to keep the town peaceful and the townspeople docile by governing through familiar leaders. The invaders need the town for its natural resources—particularly coal, and to get it the townspeople must be cooperative with the occupying force.

Colonel Lanser initially has an ironically cordial relationship with the Mayor given the circumstances, until the Mayor finds his courage and begins to assert himself. The emboldened local leader tries to warn the Colonel that the townspeople may not accept their current condition as a lasting one, and reminds Lanser that “the one impossible job is to break a man’s spirit permanently.” Colonel Lanser himself is a semi-tragic figure, torn between his lessons of the last war, and his orders—leading the occupation only grudgingly. He counsels caution to the younger officers, and is a pragmatic if not somewhat melancholy figure. The experienced Colonel expects resentment (“there are no peaceful people” he remembers), and understands that a strong response to resistance or acts of sabotage will only begin a cycle of reprisals and resistance. When one of his officers is killed after trying to force a townsperson to work, the Colonel sees the “spark that can burst into flame” ignite an earnest resistance—“so it begins!” he proclaims.

The dichotomy between the older generation who has seen the human cost of war, and the younger ones, full of faith in their system and their cause, is the most interesting theme of the book.

Slowly, both overt and deniable acts of sabotage slow down progress for the occupiers. The local miners “make mistakes” and machinery breaks, and eventually outside sponsors send dynamite in by parachute to cut the railroad. The occupiers’ reactions to mounting resistance are split between the experienced Colonel, and the naïve younger members of his staff. The dichotomy between the older generation who has seen the human cost of war, and the younger ones, full of faith in their system and their cause, is the most interesting theme of the book. Tensions build as Lanser and his staff lurch into to a familiar historical pattern: the seemingly inevitable cycle of occupation, resistance, and violence.

Steinbeck tells the story of the psychological changes within the town as resistance mounts, as the originally confident conquerors begin to fear the townspeople. Some of Colonel Lanser’s staff begin to lose faith—first in their mission, but then also in their domestic leadership. “Is this place conquered?” asks one of the younger officers of his Captain. When his Captain replies with “Of course,” the doubting Lieutenant begins to unravel: “Conquered and we’re afraid, conquered and we’re surrounded.” His once-total faith shaken, the previously confident Lieutenant observes that they’ve moved “conquest after conquest, deeper and deeper into molasses.” Hysterical, the Lieutenant has a new perspective on the war, and can see new headlines: “Flies conquer the flypaper. Flies capture two hundred miles of new flypaper!”

The Moon is Down is a quick, worthwhile, and timely read. It is not one of dramatic battle scenes, but rather an examination of how the Mayor and the townspeople grapple with what it means to be free, and their obligations as free people and citizens. Criticized as propaganda by some, it is worth noting that the novella was clandestinely printed in or smuggled into multiple occupied countries by 1944, inspiring the will to resist across Europe. After World War II, Steinbeck was even recognized by the Norwegian King due to the perceived impact of The Moon is Down in Norway. It is difficult to read this classic work in 2022, however, and think of Norway, or World War II, but rather of Ukraine. Are there Russian soldiers wondering now if “the flies have captured the flypaper”? Time will tell.

Rick Chersicla is an Army Strategist currently serving in a joint headquarters in Europe.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

Photo Description: Troops of the Wehrmacht, the military forces of Nazi Germany, in Oslo, Norway on April 9, 1940, the first day of the German invasion and occupation of Norway in World War II. The soldiers are equipped with greatcoats, steel helmets, studded jack boots, Karabiner 98k rifles and field gear. They are marching down the Karl Johans gate Street while civilians have gathered on the pavements as spectactors of the show. Unarmed Norwegian police in dark overcoats and British brodie helmets help maintain law and order. In the background are the Royal palace, the buildings of University of Oslo, etc.

Photo Credit: Henriksen & Steen (Photographers in Oslo, Norway) / National Library of Norway