Success demands readiness to ’embrace the suck’ [but also to] possess the judgment to temper brawn with thoughtfulness

Life is too short for bad beer. People of all ages pass such truths through generations, peers, and organizations. However, the Army may be developing junior leaders with a habit of not only drinking, but also appreciating, bad beer. Lest you think I am impugning the discernment of the Army’s young officers, “bad beer” is in this case a metaphor symbolizing a willingness of those same leaders not only to accept but somehow to endorse nonsensical decisions under the guise of being tough. Consuming bad beer is not an economic decision of buying the cheapest brew but a cultural decision of being hooah. Such tendencies, without the application of sound judgment, are bad for soldiers, bad for the Army, and bad for the nation.

Like many WAR ROOM readers, I have family and friends who are company-grade officers in formations across the services. They have demonstrated exceptional performance in and commitment to their units. They represent the company-grade officers that the Army wants (and needs) to be effective in future wars.

However, those same officers drink bad beer. Not always, of course; but sometimes – and sometimes willingly. One high-performing company-grade officer recently related how a group of fellow officers met at a local brewery. The place had a reputation for good food and a relaxed atmosphere. Upon arrival, they each ordered a beer and sat back to enjoy the camaraderie that results from the successful completion of a difficult training event. After the beer was served, everyone quickly realized that the quality of the beer did not come close – not even a little bit – to their expectations. This was not a matter of individual preference; no one liked the beer and they all mentioned (several times) that they should not be drinking (or paying for) beer they disliked. Yet, as the officer later related, something odd happened: they kept ordering (and drinking) more bad beer.

You may think that perhaps the officers were simply too lazy to get up from a lousy bar to go somewhere different. Maybe they just wanted to get [insert colloquial term for “deeply inebriated”]. Or maybe the quality of the conversation was such that no one wanted to leave. Maybe they were avoiding insulting the local brewer in a misplaced concern for civility (“Let’s not offend the local populace.”) Whatever the reason for their choosing to continue to drink bad beer, the story struck me as an apt symbol of a deeper potential problem: losing the capacity to walk away from bad beer.

Military culture is notoriously macho and celebrates enduring (often extreme) hardship, from Parris Island to Ranger School to BUD/S. This is rooted in the violent, nasty, physically demanding character of war. “Embracing the suck” is therefore a virtue for soldiers, marines, sailors, and airmen. It is a sign of mental strength demonstrated through the acceptance of the horrible things we cannot change, to paraphrase Reinhold Niebuhr.

Moreover, demonstrating the individual toughness demanded of military service has often manifested itself in heroic ways. Every service needs leaders with the passion and drive to accomplish every assignment. Military lore is full of tales of leaders who motivated subordinates by personal acts of bravery or endurance – things that ordinary folk may consider ludicrous. From Alexander the Great leading his troops through the breach at the siege of Tyre to “Jumpin’ Jim” Gavin leading his troops out the doors of airplanes, for the military professional, sharing in hardships and risks of war has been the essence of military leadership by example. Creating a climate in which such toughness is commonplace – even to the point of challenging oneself and others to be tougher still (“embracing the suck”) – prepares soldiers and units for their duties, even in the most extreme circumstances.

Those who embrace the suck are participants (witting or not) in a long history of philosophical inquiry into the nature of a life well lived. Classical stoic philosophers such as Epictetus, Seneca, and Marcus Aurelius talked about embracing the suck. Admiral James Stockdale memorably and movingly described how he embraced the suck during years of captivity in North Vietnam, drawing strength from the teachings of Epictetus. Embracing the suck is not a uniquely western idea. Life has sucked at times for all people everywhere. Laozi, the author of the Dao De Jing, talked about it, as did the unknown author of the Bhagavad Gita.

Embracing the suck is an integral part of the Army’s high performance orientation and critical to its effectiveness. “Performance orientation” is an academic term that for the “Can Do” attitude that is common in U.S. military organizations. To prepare for war, some consumption of bad beer is necessary to prove to oneself and others that each is capable of performing beyond expectations. The U.S. Army rightfully possesses this orientation in spades.

Furthermore, pushing people to their limits is essential to building a strong military. Extending and realizing human potential is foundational to the Army’s operating concept and requires leaders who “thrive in ambiguity and chaos.” Success demands readiness to “embrace the suck” when necessary.

In summary, there is real power and strength in the ability to keep your spirit amidst hardships beyond your control, and to push yourself beyond your known limits of endurance.

However, it is an entirely different thing, and not at all admirable, to seek out or thoughtlessly embrace unnecessarily bad circumstances. The Army’s culture often appears to celebrate embracing the suck to such an extreme that officers will keep on drinking bad beer when such suffering is unnecessary, and without meaning or purpose. Even worse, they may convince themselves that such lousy-tasting beverages are not so bad, after all. Such a perspective is problematic.

As much as we want officers who can suffer and keep going, we also want officers with good judgment. The complexity of concurrent multi-domain coordination also demands that company-grade leaders possess the judgment to temper brawn with thoughtfulness. This thoughtfulness is not indecisiveness, insubordination, or cowardice. It is the ability to consider the nuances of a situation, to understand a commander’s intent and correctly situate it in a complex and ambiguous situation. It is the street smarts that informs leaders when and how to act; some consider it wisdom.

Mindlessly embracing the suck is not a virtue. It leads us to continue to do stupid things when better alternatives are available and the situation permits the exploration of those alternatives. When we begin to lose the ability and willingness to challenge decisions or policy in the name of “embracing the suck” the profession is not developing the judgment required by effective leaders. Why not? Because the former suggests the passionate accomplishment of any task without question. However, the complexities of the current operating environment combined with the basic requirements of mission command demands that leaders at every level not only do things right, but also do the right things. The professional challenge is whether too much of a good thing is actually breeding a dysfunctional habit.

In the classic movie, Remember the Titans, Coach Bill Yoast challenges the new head coach, Coach Herman Boone: “There’s a fine line between tough and crazy, and you’re flirting with it.” Army culture is flirting with a similarly fine line between embracing the suck and blindly following foolish directives, even if it is reflected in poor beverage choices. This nuanced distinction is the essence of double-loop learning and, therefore, critical for every leader who wishes and deserves both retention and promotion. Army culture has taught them well – maybe too well –to embrace the suck, even if the challenge is not hard, but just stupid.

A second Problem with this punishing culture is that it unwittingly breeds mediocrity

The Army’s culture of embracing the suck has another significant cost: it often makes bad ideas much worse. Lower-level leaders assume that leaders at higher levels have vetted “taskings” so that stupid instructions have been modified or dismissed altogether. Such action breeds confidence and commitment at lower levels where leaders accomplish those assignments with zeal. However, the Army is comprised of imperfect people, and some tasks are simply passed down from higher to lower levels without scrutiny. Commanders (or, more likely, their staffs) sometimes add tasks as they pass through levels of command so that everyone is assured that the commanders’ guidance is not only achieved, but also exceeded. Why else would soldiers standing in a Brigade Change of Command scheduled to start at 1000 be required to be in company formations at 0630?

More than standing in formation extremely early, some other implications of this competitive cultural tendency deserve consideration. First, cultural expectations of blindly following directives, especially questionable ones, can fracture the trust relationship between the profession and its junior leaders. Things that sound stupid to junior leaders might be because they have not yet developed the maturity to understand the requirement. Of course, some consumption of bad beer is necessary to orient soldiers to the difficult tasks that they face. Nevertheless, the clear articulation of “Why?” demonstrates a thoughtfully considered requirement. On the other hand, maybe the requirement is, in fact, stupid.

A second problem with this punishing culture is that it unwittingly breeds mediocrity. An organization that lacks the willingness to prioritize, thereby expecting lower-level leaders to do all things, creates a “check the box” mentality. High performance organizations have a singular focus (Jim Collins calls it a hedgehog concept) that orients all members on a narrowly-defined responsibility. Numerous non-critical tasks consistently landing in the laps of our company-grade leaders signals that the Army cannot identify what is most important and mediocrity ensues. Reserve Component leaders face a unique challenge with such directives. Because time is a zero-sum resource, embracing the suck of standardized, large-group, power point training over mission essential readiness suggests that mediocrity is the desired outcome.

Excessively embracing the suck brings additional costs to the Army by increasing the risk that high quality young leaders leave. Our best personnel have the best options outside of the Army. All other things equal, people with great alternatives to the Army are less likely to just grit their teeth and deal with it every time the Army adds a dozen more rocks to their rucksacks. A culture of phony toughness can cause the highest performing junior leaders to become irritated with such false bravado. They have excelled in tough situations and may get frustrated with a culture that demands the unconditional acceptance of trivial requirements. Instead, they may choose to leave the military in search of a different organization that is committed to excellence in both its word and deed, accepting and expecting healthy dissent to improve norms and processes.

Questioning (and at times challenging) stupid tasks is a requirement of every leader at every level. Mindlessly (or worse, intentionally) transferring burdensome tasks to subordinates and expecting them to take the risk of ignoring them, is a stark example of incompetence (or cowardice). Leaders must do better at tempering the nuanced distinction between valid, difficult, dangerous, and stupid tasks.

One of the Army’s best leader developers, LTG(R) Walt Ulmer, former commander of III Corps, was fond of saying, “If it’s dumb, it’s not our policy.” In his work, Ulmer willingly provided examples of stupid policies he uncovered and challenged throughout his honorable military career. We need more leaders – especially at the senior level – to embrace such a perspective.

Secretary of the Army Mark Esper and Army Chief of Staff General Mark Milley have recently targeted less important mandatory requirements of AR 350-1 for deletion. This is a useful and symbolic movement in the right direction; but these changes are not enough. Every leader (and their corresponding staffs) must actively enforce such a prioritizing perspective at every echelon of command. The Army’s culture will not change in this domain unless every leader acts to reduce stupidity.

Development of judgment within all ranks of Army formations is essential not only for current readiness but also for future effectiveness in an increasingly complex environment. Encouraging and reinforcing subordinate questioning of perceived stupidity is necessary in the development of that judgment. Otherwise, our company grade officers will continue to drink bad beer – simply because it has been ingrained in them to prove that they are tough enough to “embrace the suck.” Life is simply too short – and the profession too important – for such mistakes.

Dr. Craig Bullis is Professor of Management at the U.S. Army War College. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the U.S. Army War College, U.S. Army, or Department of Defense.

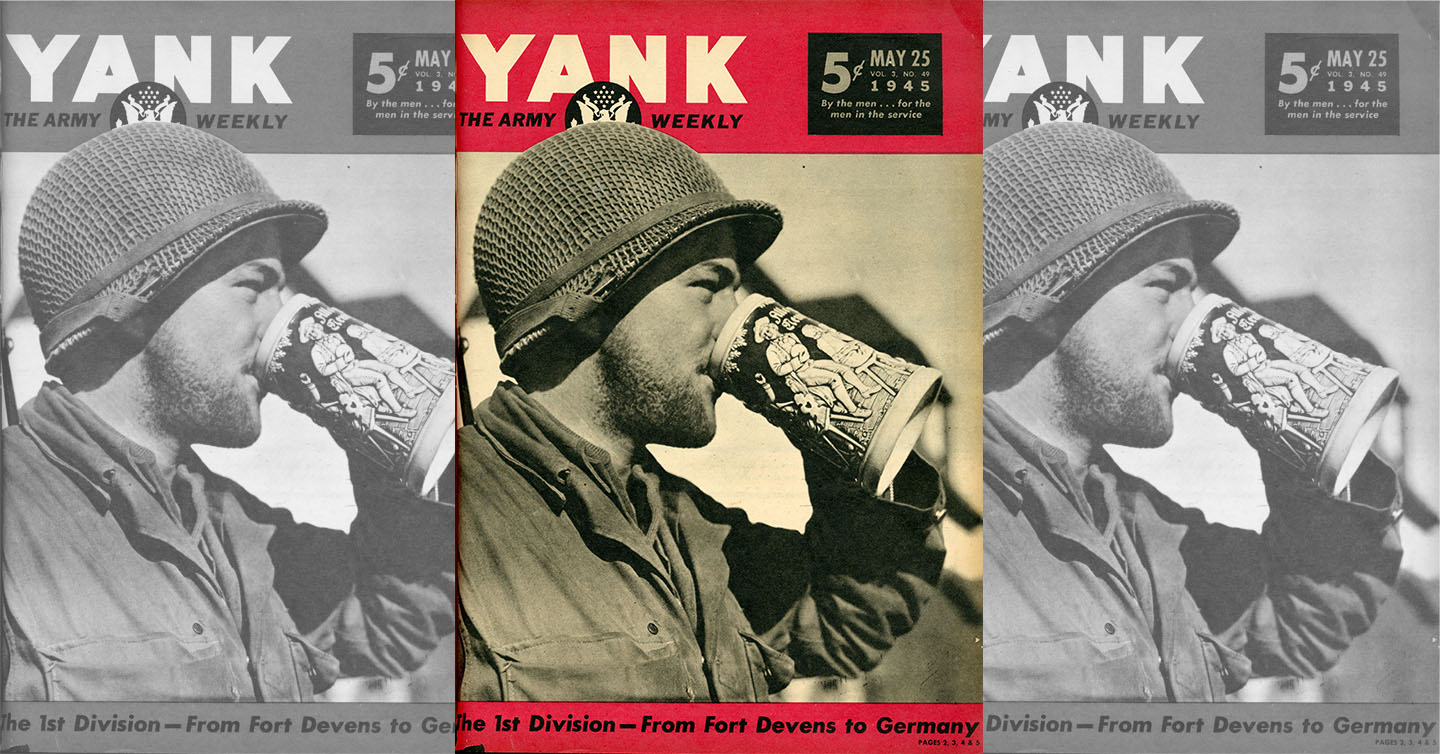

Image: Cover of YANK Magazine from May 5, 1945 showing PFC Grant Crawford of Molino, an engineer with the 26th Infantry Division, drinking beer out of a German stein, public domain.

Image Credit: With thanks to Mr. Rodney Foytik, Army Heritage and Education Center.