EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the fourth and final in a four-part series of articles on how national security professionals should (and should not) approach the fraught task of learning lessons from something as complex as war. We have assembled a team of sharp minds and pens in the business to apply their varying perspectives to the question opened by the Army War College’s Chase Metcalf, how do we think about learning lessons from war? It is a fitting end to 2023 and, unfortunately, will likely be essential in 2024 as well.

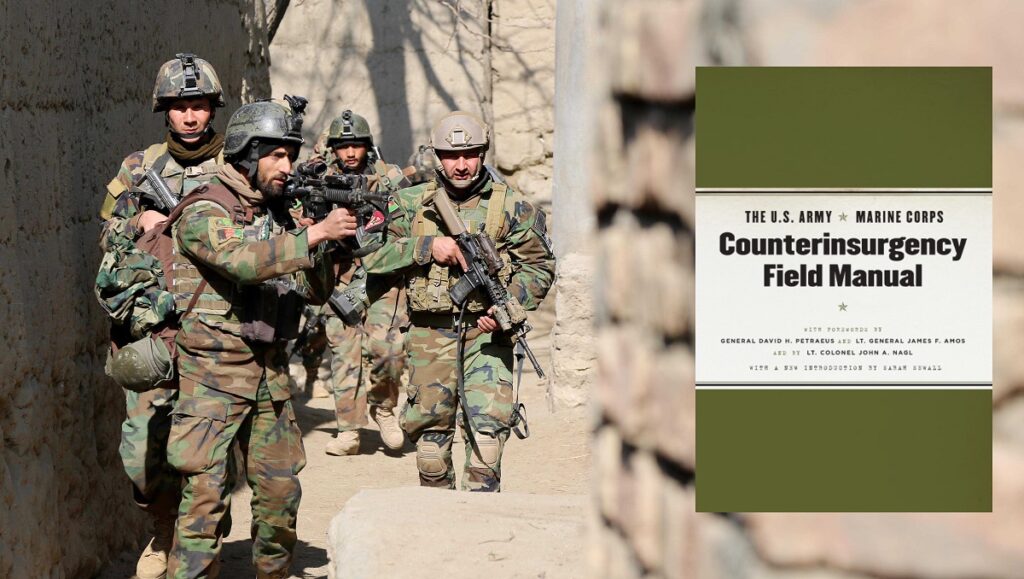

For the U.S. Army specifically, the lessons “learned” from previous counterinsurgency operations quickly became a kind of intellectual straitjacket during the Iraq and Afghanistan wars.

The wars in Ukraine and Gaza offer a laboratory of study for military professionals, historians, and analysts. Studying a current war to help organizations understand and prepare for future conflict is not new. Future U.S. Civil War Union General George B. McClellan, for example, went to Crimea in 1855 with two fellow West Point graduates to gain insights from the Crimean War for application to future combat. Ten years later, it was common for British army officers to spend time with the Confederate Army, so that they too might study operations in the American Civil War and apply what they had learned to their army back home.

In the same spirit, it makes perfect sense for American military organizations to study both the war in Ukraine and the war in Gaza, and to draw insights from both.

But as the U.S. Army studies these two wars for insights, let’s drop the “learned” from the phrase “lessons learned.” Lessons learned assumes that an insight—a “lesson”—from these current wars can also, at the same time, be “learned”—that is, incorporated into the training and strategies of another military. This is a highly problematic assumption.

For the U.S. Army specifically, the lessons “learned” from previous counterinsurgency operations quickly became a kind of intellectual straitjacket during the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. There was only one perceived way to do a counterinsurgency operation correctly: which was to follow the appropriate “lessons” from history, and strictly adhere to the directives in the U.S. Army’s 2006 counterinsurgency field manual, Field Manual (FM) 3-24. This field manual was written under the supervision of General David H. Petraeus, and it came to embody the sort of intellectual straitjacket that considered any type of creative thinking about U.S. military strategy in Iraq and Afghanistan, any idea that could not be found within its pages, as a kind of heresy. For example, the first chapter of FM 3-24 directed counterinsurgent forces in any war to view a population in one specific way:

In any situation, whatever the cause, there will be [a population that has] …an active minority for the cause [of the counterinsurgent]; a neutral or passive majority; an active minority against the cause.

But does such a view describe the population of Baghdad in 2006, at the height of the Shia-Sunni civil war? Does such a view, for that matter, reflect what Israeli soldiers are experiencing in Gaza today? During America’s counterinsurgency wars, the advocates of counterinsurgency (COIN) pushed the construction of this narrative, which many in the U.S. Army came to believe. By the same token, they argued if this population-centric counterinsurgency narrative drawn from the “lessons” of history could just be “learned,” the U.S. would eventually prove successful in Iraq and Afghanistan. Only as the result of U.S. wars in both Iraq and Afghanistan—and especially the latter—have shown, the COIN advocates were wrong; that narrative was proven time and again to be a false one.

And yet during the Iraq and Afghanistan years, the COIN advocates deployed so called “lessons learned” from previous counterinsurgency wars, such as the British in Malaya in the 1950s and the U.S. in Vietnam from 1965-1972, arguing that those wars demonstrated there was a “right way” to do counterinsurgency. In Iraq, from 2003 to 2006, and in Afghanistan, as early as 2005, the COIN advocates argued that U.S. Army had not fully come to understand those lessons. The U.S. Army was failing in Iraq, they argued because the Army was not applying the lessons of a population-centric counterinsurgency strategy.

During these years in the mid-2000s, the arguments of the COIN advocates became so hyper-charged that they began to make assertions that all future wars would not be anything like the large scale combat operations of the past, but instead would be wars fought among the people, over “hearts and minds.” These advocates went so far as to argue that the “strategic environment” had changed so much with Iraq and Afghanistan that a full restructuring of the U.S. Army was necessary in order to optimize it for future counterinsurgency operations.

Even today, the remnants of the COIN advocates’ way of thinking still lingers. Political scientist Robert Pape, for example, recently argued in a CNN opinion piece that Israel should pay attention to the lessons of the U.S. counterinsurgency wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and understand what he called “counterinsurgency math.” In his piece, Pape quoted General Stanley McChrystal from a 2009 speech where McChrystal suggested that the right approach for Afghanistan was the same as Petraeus’s counterinsurgency approach in Iraq: protect the population, separate the people from the insurgents, kill or capture the latter, be patient, and, if you do all of this, you will likely succeed. Yet the idea that Petraeus’s counterinsurgency methods in Iraq in 2007 and 2008 turned the war around and chalked up a win for the U.S. Army have been, at this point, largely and effectively disputed.

Fortunately today for the national security of the United States, the U.S. Army did not transition to a force for “war among the people” as some COIN advocates would have liked; nor should it listen now to current analysts advocating for these lingering, failed ideas.

Indeed, if there is one large insight that has emerged from the war in Ukraine and the war in Gaza, it is that large scale combat operations are decidedly not a thing of the past…

But imagine if the U.S. Army had done what the COIN advocates had called for, and reorganized to optimize for future COIN operations because it thought conventional, high-intensity combat operations were a thing of the past? Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the resultant high-intensity conventional combat, and Israel’s conventional approach to destroying Hamas in urban combat, and the direction of future wars that these current wars point to, shows that such a reorganization would have been, a monumental mistake for the U.S. Army and the joint force.

Indeed, if there is one large insight that has emerged from the war in Ukraine and the war in Gaza, it is that large-scale combat operations are decidedly not a thing of the past, and that the US Army, along with the rest of the joint force, might well find itself in a similar kind of shooting war in the near future.

So as we go forward in preparing for present and future war, let’s avoid the type of intellectual straitjacket that the counterinsurgency era had on the U.S. Army.

Indeed—and this is especially true for the U.S. Army—Ukraine and Gaza offer a view into the types of combat that U.S. forces mostly did not experience in Iraq and Afghanistan. In the case of Ukraine, that is sustained large-scale combat between two conventional forces. With Israel’s war in Gaza, it is a sustained level of high-intensity urban combat against a guerilla force. To be sure, in Iraq there were intermittent periods of high-intensity urban combat in cities such as Baghdad and Fallujah, but not in the way that in unfolding in Gaza.

There are several other large insights from Ukraine and Gaza that the U.S. Army and joint force should pay attention to. The most immediate and apparent is that attrition of manpower and equipment is integral to large-scale combat operations. In Ukraine, for example, nearly two years into the war, Russia has suffered close to 300,000 casualties, of which approximately 120,000 have been killed in action. When one compares this to nearly 41,000 Americans killed in the seven-year war in Vietnam, one can appreciate the high amount of attrition in the Ukraine War.

The U.S. joint force is arguably one of the most competent and professionalized power-projection military forces in the world, with an abundance of exquisite, precise weaponry. Indeed, a large insight emerging from Ukraine specifically is the importance of having plentiful stockpiles of precision and non-precision munitions. A robust U.S. defense industrial base, therefore, is needed to sustain U.S. support efforts in Ukraine and Israel and, if need be, allow the U.S. joint force to sustain any major combat operations in the future.

Another significant insight that has become clear from the Ukraine War, and is emerging from Israel’s war in Gaza, is that the offensive is still the dominant form of warfare. In the initial months of the Ukraine War, a popular argument among some defense analysts was that the defensive had become ascendant in modern war.

Not true.

Ukraine’s, desire to produce a mechanized offensive force to break through the current stalemate and evict Russian ground forces from its lands is a testament to the dominance of the offensive. The only way Ukraine can hope to evict Russian forces from its homeland is through offensive operations. Staying on the defensive for Ukraine will only aide Putin’s maximalist aims in Ukraine. Similarly, Israel’s war in Gaza further proves the flawed thinking that the defensive has become the dominant form of war. Does anyone really believe that Israel’s military can achieve its political aim of Hamas’s destruction by remaining on the defensive?

Lastly, and probably most importantly, Ukraine and Gaza demonstrate that war is “cruelty and you cannot refine it,” as Union General William Tecumseh Sherman noted more than 150 years ago during the American Civil War.

The U.S. Army therefore must finally jettison the leitmotif from its counterinsurgency legacy that wars can be won by soldiers wearing velvet gloves and applying supposed cutting-edge, enlightened counterinsurgency methods designed to protect populations and bring about victories in a more precise and principled way. Former Chairman of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff Mike Mullen encapsulated this rosy view of war in 2010 when he said:

We must not look upon the use of military forces only as a last resort, but as potentially the best, first option…we must not try to use force only in an overwhelming capacity, but…in a precise and principled manner. Ukraine and Gaza show that Sherman’s view of war as “cruelty” that cannot be “refined” is as correct today, and will likely remain so into the future, as it was in 1864.

Gian P. Gentile is a retired U.S. Army colonel, who served for many years as a history professor at the United States Military Academy at West Point. Gentile has also been a visiting fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and is a senior historian at the RAND Corporation as well as the Director of the RAND Arroyo Center.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

Photo Description: Afghan National Army Commandos with the 6th Special Operations Kandak, patrol an alley in Tagab district, Kapisa province, Afghanistan, Feb. 11, 2013. The Commandos participated in counter-insurgency operations to clear the area of hostile strongholds.

Photo Credit: U.S. Army Photo by Pfc. James K. McCann, Some rights reserved