The notion that the Trump administration’S decision was unexpected is UNCONVINCING

President Trump’s October announcement that the U.S. will “pull out” of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty set off a flurry of opinion pieces and assessments by numerous experts. Predictably, two camps emerged. One group applauded the decision, calling the Treaty a Cold War relic that should be scrapped as it handcuffed U.S. security in a changed threat environment. The other group saw it as a signal for a new and costly arms race that would lead to a more dangerous world. Both took the view that the decision was entirely one of the executive branch’s making. Whatever the merits or failings of the President’s decision, the U.S. withdrawal from the INF Treaty indicates something significant in the conduct of foreign policy towards Russia and China under President Trump: an emerging alignment between the President and the Republican majority in the Senate. This alignment leaves behind the internal party disagreements that characterized U.S.-Russia policy when the President took office almost two years ago. Combined with the U.S.’ hardening stance toward China, withdrawing from the INF Treaty may mark the beginning of a new period in international security.

President Ronald Reagan and Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev ratified the INF Treaty in December 1987, and the Senate consented unanimously five months later. The accord required that the United States and the Soviet Union eliminate all ground-launched ballistic and cruise missiles with ranges between 500 and 5,500 kilometers within three years after the Treaty entered into force, and that neither party possess such weapons in the future. The rationale for the Trump administration’s decision to upend the agreement was that the Russians have been violating it since 2014, which the Russians deny.

Can the President simply withdraw from the INF Treaty? One critic, asserting that Congress has the right to counter the Trump administration’s plan, questioned whether it has the backbone to do so. Yet the legal grounds for such a move are murky, depending on a reference from Alexander Hamilton’s Federalist No. 75, as the critic asserted that the legislative branch “commands the clear constitutional authority to prohibit Donald Trump from terminating” the Treaty. However, Article XV of the INF Treaty states, “each party shall, in exercising its national sovereignty, have the right to withdraw from the Treaty if it decides that extraordinary events related to the subject matter of this Treaty have jeopardized its supreme interests.” In that case, the party would “give notice of its decision to withdraw to the other party six months prior to the withdrawal.” The legal precedent for members of Congress filing suit on the claim of constitutional authority over treaty withdrawal is a single case (Goldwater v. Carter) brought before the Supreme Court in 1979. The Court saw the issue as a political question and dismissed the complaint. Thus, the legal basis for congressional opposition is weak.

Political opposition is a different matter. Indeed, a few Republican senators voiced their concern about the decision. Senator Rand Paul stated, “It’s a big, big mistake to flippantly get out of this historic agreement.” He urged the president to open negotiations with the Russians to update and expand the treaty. Senator Bob Corker, Foreign Relations Committee chairman, hoped the administration was using the declaration to gain leverage, and thereby, prompt the Russians to return to compliance. He opined, “I hope we are not moving down the path to undo much of the nuclear arms treaties we have put in place.” Yet this opposition does not seem to reflect the sentiment of the majority of Republicans.

The administration’s declaration should not have come as a surprise to Republican Senators on the Foreign Relations Committee. The administration had willing accomplices on Capitol Hill. Moreover, as early as 2013, the Defense Department has been planning for an end of U.S. participation in the INF Treaty, a year before the Obama administration publicly announced its protest that the Russians were in violation. Further, the Defense Department has been examining potential missiles it could develop and deploy that would have ranges between 300 and 3,400 miles and therefore, not be treaty compliant. Civilian and military Defense Department officials had been openly and clearly expressing their concerns in congressional testimony for the past five years.

the U.S. withdrawal from the INF Treaty indicates something significant in the conduct of foreign policy

What about the role of Russia in prompting President Trump’s choice? The discourse about Russia’s role in the global security environment has been changing for some time, though the shift accelerated in 2014, with Russia’s occupation of the Crimea and its war in Ukraine. In August 2016, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Joseph Dunford, laid out the “4+1” framework, identifying Russia and China along with Iran and North Korea, as the principal threats to the United States, its allies and partners. (The plus one was “violent extremism.”) Thus, after a decade of strategic distraction with the so-called War on Terror, the United States would now focus on the most serious threats to the nation’s survival and its vital interests. Dunford’s framework, now termed the “return of great power competition,” found a place in the December 2017 National Security Strategy (NSS). Yet arms control received little attention in the NSS. Where does the INF Treaty come in?

The Defense Department’s February 2018 Nuclear Posture Review was unequivocal in its questioning of Russian adherence to the INF Treaty, underscoring that the U.S. pursuit of a nuclear-armed Surface Launched Cruise Missile (SLCM) would “provide an arms control compliant response to Russia’s non-compliance with the Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces Treaty, its non-strategic nuclear arsenal, and its other destabilizing behaviors.” Thus, Russia was not meeting its international legal and political commitments and was in violation of the INF Treaty. State and Defense Department officials testified before Senate Foreign Relations Committee in September 2018 on the state of Russian arms control. The Defense Department official indicated that the U.S. response to Russian noncompliance included “preparing the United States for a world without the INF Treaty.”

Action on Capitol Hill provided other clear signals that the INF Treaty was in jeopardy. Republican Senator Tom Cotton, an Armed Services Committee member, introduced a bill in February 2017, the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty Preservation Act, to enforce Russian compliance. A companion piece of legislation was introduced by two Republicans in the House. The Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2018 provided the sense of Congress: the Russians were in a material breach of the INF Treaty, which “affords the United States the right to invoke legal countermeasures which include suspension [a term not in the treaty language] of the treaty in whole or in part.”

This year, Republicans in the House Armed Services Committee added language to the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019 requiring the President submit a determination, by January 15, 2019, of whether Russia is in material breach of its obligations under the INF Treaty. The Senate version of the bill contained no such language, and in conference, the Senate conferees receded to the House.

Given all this activity, the notion that the Trump administration’s decision was unexpected is unconvincing. Instead, it suggests something different: the formation of a new foreign policy consensus between a Republican Congress and the executive branch regarding U.S.-Russian relations on arms control. It is not unique for the defense committees to actively promote U.S. foreign policy in arms control, overshadowing the foreign affairs committees. The legislation also points to the House of Representatives’ willingness to play a more prominent foreign policy role using its legislative powers to do so.

Arms control issues were debated strenuously during the Cold War because, as Pat Towell has pointed out, they are “fraught with some significant implications for U.S. defense policy and budgets.” The arms control tug-of-war between the Senate and the president consisted of “elaborate and closely coupled assumptions about the nature of the military balance in question… and highly technical calculations.” Congress definitely has an institutional interest in this issue and should ensure it is consulted. The challenge for both branches today is to rebuild that framework based on an evolving strategic environment.

In 1988, as the Senate debated the INF Treaty in its advice and consent role, Democratic Senator Sam Nunn, chairman of the Armed Services Committee, offered a salient point about the congressional role in arms control. He held that Congress must be assured that the administration was entirely transparent about how the Treaty fit into U.S. foreign policy objectives and its military strategy. Nunn’s concern is worthy of consideration today. It will take an active and assertive Congress, perhaps one which even challenges the president, to hold the administration accountable regarding how withdrawing from the Treaty is part of a comprehensive national security policy framework, and not a haphazard action. Still another question remains to be answered: with a divided Congress come January 2019, will it be able to act effectively in that oversight capacity?

Frank Jones is Professor of Security Studies at the U.S. Army War College. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, U.S. Army, or Department of Defense.

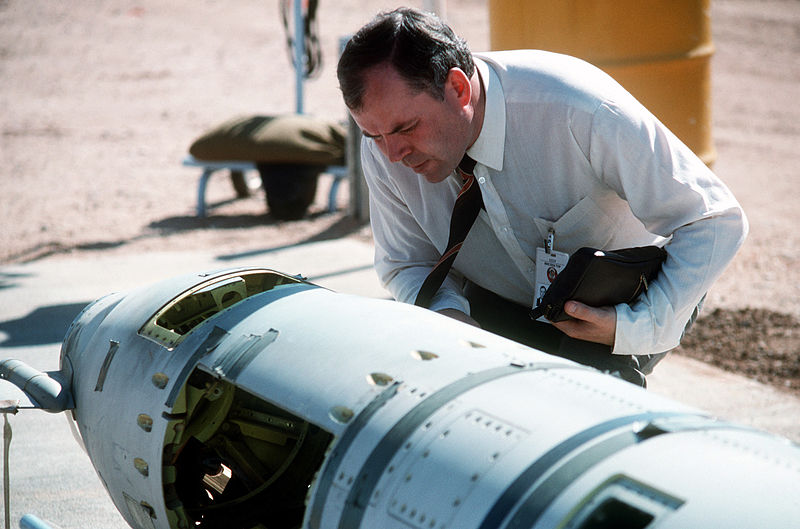

Photo: A Soviet inspector examines a BGM-109G Tomahawk ground launched cruise missile (GLCM) prior to its destruction. Forty-one GLCMs and their launch canisters and seven transporter-erector-launchers are being disposed of at the base in the first round of reductions mandated by the Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces Treaty.

Photo Credit: MSgt Jose Lopez, U.S. Department of Defense photo