Competition Space Analysis (CSA) is an event and network-based methodology to map malign actor activities, revealing their foci and connections between seemingly benign organizations and people.

In modern great power competition, much of the U.S. military’s focus has been on ensuring military capabilities exist to secure Europe against Russia and counter China’s military capabilities in the Indo-Pacific region. However, hybrid threats and grey-zone tactics by malign actors are an increasingly serious threat to U.S. efforts to establish influence in strategic countries. The U.S. military, primarily through Special Operations Forces (SOF), conducts indirect military actions to strengthen local populations’ resiliency to such threats. In conjunction with other agencies including the State Department, it works to counter malign influence. However, no widely-known framework currently exists to help interagency teams visualize and understand the breadth of malign actors’ overt operations, activities, and investments (OAIs). The U.S. military should use network and operational experience gained from counterinsurgency campaigns in Iraq and Afghanistan to develop a malign actor event and network data base – in military vernacular, a common operating picture—with interagency partners to help counter malign actors’ OAIs and synchronize United States Government (USG) efforts in contested spaces. Competition Space Analysis (CSA) is an event and network-based methodology to map malign actor activities, revealing their foci and connections between seemingly benign organizations and people. By visualizing malign activities over time, CSA allows the USG interagency to use targeted programming to better compete with other countries seeking to expand their influence in-country. This article will discuss: 1) the depth and flexibility of Competition Space Analysis, 2) a hypothetical case study of effective application of Competition Space Analysis, and 3) the inherent potential of the expanded use of Competition Space Analysis for interagency efforts to plan and synchronize operations to counter malign activity efforts.

Why Competition Space Analysis?

CSA’s ability to inform a U.S. whole-of-government approach during great power competition is essential due to malign actors’ use of whole-of-society approaches and their military theories about using information and shared history in weaponized narratives against the U.S. in key areas around the globe. To achieve this, Competition Space Analysis codes political, economic, social, shared history, and nostalgic historical events. This allows for robust analysis through a whole-of-government lens.

How Do You Solve a Problem You Can’t Describe?

The Department of State (DoS) and various interagency organizations use the Integrated Country Strategy (ICS) and Country Development Cooperation Strategy (CDCS) to ensure that in-country activity advances U.S. policy priorities as laid out in the National Security Strategy, the State-USAID Joint Strategic Plan, and State regional and functional bureau strategies. However, while these strategic documents identify malign foreign influence as something to combat, they lack a finer-grained picture of the physical actions, resources, and intent of malign actors. Without a useful methodology, interagency actors cannot effectively counter malign actor networks.

While operating in Eastern Europe, our interagency team comprised of DoS and DoD individuals developed such a methodology, which has since become known as Competition Space Analysis (credit to MAJ Charles Noble). Competition Space Analysis is an event data (behavior data) and network science approach that takes malign actor events and sorts them into various themes, e.g., economic, political, and shared history. This codification of events draws extensively from social science contentious politics literature were event data has been used “to trace the rise and fall of movements, shifts in goals or tactics”, and the geographic patterning of events. Long term, Competition Space Analysis can provide a wealth of analysis and robust statistical testing of malign actor events similar to contentious politics analysis methods. With this knowledge, DoS and USAID can better focus and target their counterprogramming efforts on specific locations and understand local and malign actor networks. Additionally, Competition Space Analysis informs and allows the interagency to observe malign actors’ reactions to their counterprogramming efforts.

Event Data: How Rivals Also Vie for Hearts and Minds

As mentioned previously, the event data portion of Competition Space Analysis sorts malign actor events into standardized themes, which allows quick identification of what issues those actors are engaging with. Depending on the actor, the country, and the audience, these themes may include economic coordination, revisionist history, family conservation, and language or education-themed events. Over time, these events yield insights into malign actor operational aims and disposition. Because these themes are standardized and well-described, they can be reliably identified and coded by successive team members over a long timeline, allowing robust regression and multi-variable analysis. In addition, events conducted on a given theme can then be correlated with variables including municipal demographics, voting data, and other sociological indicators. This capability is vital because great power competition is ultimately local and its success or failure is dependent on local demographics, social trends, and cultural characteristics. The interagency may have a big-picture understanding of malign actors’ strategic goals or lines of effort, but the informed analysis from Competition Space Analysis helps practitioners on the front lines of great power competition contextualize seemingly random operations by malign actors, identify patterns—and take action.

Network Mapping: Who, What, Where, and Why?

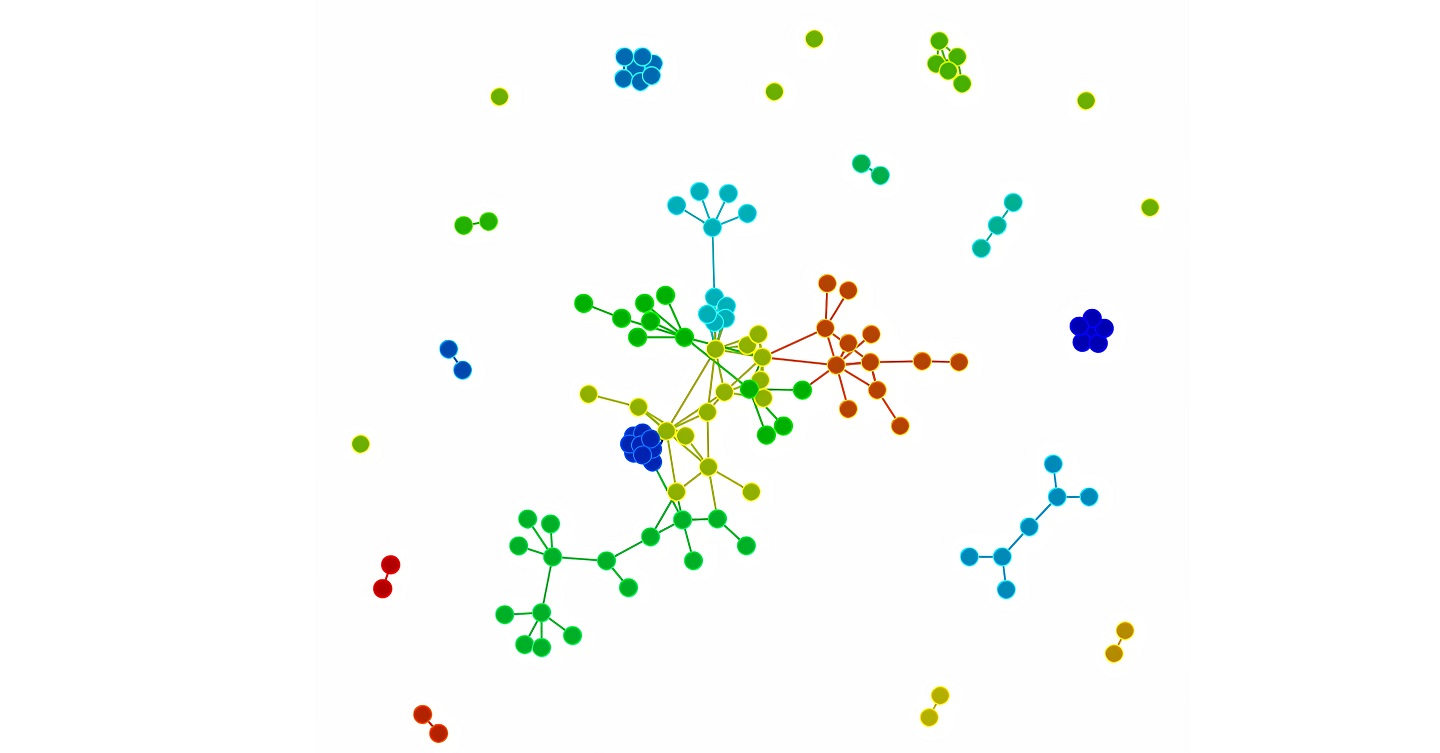

In addition to event data, CSA also focuses on network mapping using network science techniques. Malign actor networks are developed by analyzing open-source information such as social media posts from malign actors’ embassies, press releases by affiliated organizations and government agencies, and press coverage of events. This open-source information provides data on time, date, location, key individuals, and key organizations that sponsored or facilitated each event. This data in turn informs our reconstruction of malign actor networks. This capability of Competition Space Analysis was informed by the DoD’s Attack the Network efforts to curb threat networks and IEDs during the Global War on Terror (GWOT), network engagement doctrine, and new countering threat networks doctrine.

Soft power is most effective when it is publicized; we can use our competitors’ own posts and press releases to identify their frequent partners, track their favorite themes, map their events, and, ultimately, determine what their objectives are.

Mapping competition space networks is conceptually no different from network mapping an insurgent organization. In fact, it is considerably easier due to the rate of information shared by malign actor embassies and agencies conducting hybrid warfare and grey-zone activities. Soft power is most effective when it is publicized; we can use our competitors’ own posts and press releases to identify their frequent partners, track their favorite themes, map their events, and, ultimately, determine what their objectives are.

With this information, our team used social network analysis to understand what actors or organizations hold central positions within the malign actor network, how information flowed within the network, and the structure of the network as a whole.

How CSA Imposes Costs on Our Competitors

Competition Space Analysis informs and empowers the interagency to impose costs on malign actors. It provides us data on: 1) Where and what type of events took place, 2) The frequency of events over time and proportion of nationwide events that fall within our scope of malign influence, and 3) The identities of key individuals and groups who facilitated or played a key role in the events.

As an example, Competition Space Analysis event data shows that the “Stonegard (hypothetical location)” municipality has seen a malign actor conduct three economic-themed events over the last two months. A review of historic CSA data shows that, over the last year, malign actors have only conducted 10 economic-themed events, most of which took place in the capital. During the monthly DoS interagency coordination meeting, interagency representatives discuss the increased activity in “Stonegard” and identify an opportunity to counter-program. USEMB Public Affairs Section (PAS) develops a plan to step up activities and messaging to emphasize U.S. economic support in Stonegard. USAID reps identify development funds that can counter malign actor activity in the municipality and surrounding region. A SOF cross-functional team representative recommends the Civil Affairs team meet with local community leaders to identify potential Overseas, Humanitarian, Disaster Assistance, and Civic Aid (OHDACA) projects in the “Stonegard” municipality, while the Military Information Support Team coordinates with USEMB Political Section to meet with local governance to support their emergency communications plan. If a military base is located near “Stonegard”, there also exists the potential for U.S. and host nation military cooperation through a training mission by a Special Forces Operational Detachment Alpha. Immediately, “Stonegard” becomes contested space using a whole-of-government approach powered by CSA. Additionally, Competition Space Analysis informs the success of our efforts over time by monitoring future events in the “Stonegard” municipality. Costs are imposed on malign actors and synchronized using Competition Space Analysis data. Ideally, the interagency influences the local government and community organizations to shy away from malign actors.

False Information

One potential challenge to network mapping is the possible deliberate introduction of false personas and event information by malign actors in an attempt to skew the network. While this a legitimate concern, it is somewhat limited by the whole-of-government approach malign actors often take when influencing populations. Malign actors often host highly publicized events to build rapport with communities. Faking these events would discredit malign actors with their target audiences and would be unnecessarily costly for their image. Additionally, analysis of photographs of the events, individuals seen using microphones or handing out certificates, and speaker quotes in press releases can act as evidence of an individual’s placement in the network to reduce coding inaccuracies from false information attempts.

Conclusion

For great power competition, CSA should be the foundation from which we develop our strategic campaign plans in each country affected by malign actors. Our experiences–as regional planner for a Theater Special Operations Command and a Special Operations Civil Affairs Team Commander and as a State Department Public Diplomacy Officer in Washington and overseas—have shown us that interagency teams operate in their own individual “silos of excellence” and lack a malign actor event and network data base–or a common operating picture—to help them counter malign actors’ OAIs and synchronize United States Government (USG) efforts in contested spaces. This increased need for collaboration among the interagency has been documented by RAND in 19 of 36 reports on USG strategic communication. The initial Competition Space Analysis brief to embassy leadership changed their perception of malign actor activity and led to more focused counterprogramming. As DoD continues to develop strategies in a great power competition, it has the abundance of resources, analytical experience, and flexibility to conduct Competition Space Analysis for the interagency in priority countries. Ideally, this would take place at U.S. Combatant Commands like EUCOM, AFRICOM, and INDOPACOM and inform the programming and activities of U.S. Embassies engaged in countering malign influence. This would maximize planning synchronization, because CSA analysts would be located adjacent to the Joint Interagency Coordination Group (JIACG) tasked with advising on operational planning efforts in line with the 2012 guidance on Interagency Strategy for Public Diplomacy and Strategic Communication of the Federal government. Additionally, either the J-7 or J-9 staff sections could act as a liaison, providing information and receiving requests for additional information from the country team or specific sections within the country team (e.g. USEMBs’ Public Affairs Sections, Defense Attachés, and USAID offices). To maximize CSA, interagency teams abroad could provide valuable “ground truth” through qualitative analysis to bolster CSA’s findings. An additional benefit of GCC’s hosting CSA analysts would be facilitating the US Military’s indirect action operations and nonlethal targeting operations. Competition Space Analysis could improve and support mission analysis and information preparation of the battlefield for large multi-national operations, security force assistance, influence operations, and civil-military operations. Competition Space Analysis, if adopted, must not solely reside within the intelligence community. There exists to great a possibility of Competition Space Analysis becoming overly classified and being lost as a common operating picture from which the interagency can plan and synchronize operations. For the United States to counter malign influence, it must first understand malign actor intent. Competition Space Analysis provides a data-driven methodological baseline to better understand malign actor behaviors and networks. Once networks are mapped and understood, the interagency can work together to counter them with our network of civil society organizations, international donors, and other U.S. government agencies. Competition Space Analysis is simple to train and a highly effective tool that provides our diplomats, government employees, and military with an analytical framework that allows the interagency to “achieve levels of knowledge, speed, precision, and unity of effort that only a network could provide” to compete against malign actors.

Tommy Daniel is a Civil Affairs SOF Governance Officer. Tommy has multiple operational assignments in Europe with the 173rd IBCT(A) in Ukraine, future operations planner for Task Group Balkans, and most recently, a cross-functional team leader in the SOCEUR AOR. He has a Masters of the Arts in Conflict Resolution in Divided Societies from King’s College London.

Aaron Honn is a Foreign Service Officer with the U.S. Department of State. The recipient of three State Department Superior Honor Awards, he has served in Moldova, Sweden, Panama, Canada, and Washington D.C. He has a BA from Yale University and a JD from the University of Houston. He is currently attending the National War College, from which he anticipates receiving an MS in National Security Strategy in 2022.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, Department of Defense, or the Department of State.

Photo Description: Malign actor network 2019

Photo Credit: Provideded by Tommy Daniel