EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the third of a series of three articles coming from the 2022 Kingston Conference on International Security, “International Competition in the High North,” co-sponsored by the Army War College’s Strategic Studies Institute in conjunction with three Canadian partners.

For thousands of years, the circumpolar world has been one of the most remote and least populated regions on earth.

The Arctic is warming four times faster than any other region, while glaciers are receding, permafrost is melting, and sea ice is retreating at a dramatic pace. These climatic changes are widely recognized, including by military leaders who are pondering the strategic implications for competition with Russia and China. But equally momentous changes in the human domain of the Arctic are largely being overlooked. As special operations forces are urgently relearning the fundamentals of operating in the region, they must also gain competence in environmental security. How are the human populations of the circumpolar North evolving with climate change, what are the security dynamics of these trends, and how can special operations forces connect with new diverse populations, particularly those in northern Alaska as partners in a warming Arctic?

For thousands of years, the circumpolar world has been one of the most remote and least populated regions on earth. Even today, only four million persons live above the Arctic Circle. Approximately one in ten Arctic residents is indigenous, with more than 90 different languages spoken in the northern polar region. As the Arctic warms, however, the region will, and already is, experiencing several regional population trends with military implications.

First, indigenous populations are increasing in a number of key areas in the Arctic. Northern Alaska is home to the region of the United States that sits above the Arctic Circle. Within Alaska as a whole, native communities represent the only real source of population growth in the state. The North Slope Borough in the Alaskan Arctic, for instance, grew by 21% between 2010 and 2021 to 10,972 persons, and is majority Indigenous. In Canada, residents identifying as aboriginal are expected to grow in size to over three million people by 2041. Growth in indigenous populations is important to recognize, as most of the land above the Arctic Circle in both the United States and Canada usually falls under complex tribal or native authorities.

Second, Arctic populations are diversifying. Much of this growing diversification is due to the significant need for general and skilled labor in a sparsely populated Arctic. For instance, of those approximately 11,000 inhabitants of the North Slope of Alaska, though as earlier stated most are Indigenous or White, there are significant changes. Between 2010 and 2020, the Black and Hispanic populations grew by 72% and 120% respectively; the Asian population increased almost 51%, and the Pacific Island community grew by an astonishing 209%. Approximately 7% of the North Slope is now foreign-born, and Asian-Pacific Islanders alone comprise roughly 8% of the population on the North Slope. Many of the newcomers to the area are part of the long history of Pacific migrants who have worked in Alaska for years, but are now increasingly being driven to migrate to the Arctic by climate factors. They are still being “pulled” in by high salaries for general labor in this remote area, but are increasingly being “pushed” away from their homes in the Pacific by severe climate change degradation to their local communities and economies. Furthermore, military forces deploying to the region may be surprised to find that only 67% of residents of the remote North Slope Borough speak English as their native language. It is common to hear Inupiaq, Visayan, Tagalog, Spanish, Russian, Hawaiian, Samoan, Thai, Korean, and many other languages in communities like Utqiagvik (formerly Barrow), Alaska.

Third, Arctic populations in a number of countries may become younger in the future as climate change warms the region and spurs more economic opportunities. In many remote Arctic regions of the world, few large urban settlements exist in these isolated areas that are difficult to develop and maintain, and many communities are no larger than several thousand people in size. Out-migration of younger working adults has long been a challenge as they leave their homes for larger urban areas and better economic opportunities outside of these harsh environments. As the Arctic develops economically through warming, it may become a region that is ultimately more attractive to younger, single people and working families.

Fourth, the Arctic will likely have an increased presence of fly-in, fly-out workers, at least for the foreseeable future, to address its labor shortage of skilled workers. This is already the case in some communities such as Prudhoe Bay, Alaska, where many energy workers, engineers, and other “Slopers” serve rotating shifts in company man-camps on the tundra as they come in from other states for work. Likewise, because much of the Arctic is medically underserved, many Arctic communities rely on doctors and or travel nurses who rotate in and out for limited periods of time during circumpolar assignments. National Science Foundation researchers, academics, and other scientists are increasingly coming to the Arctic for deployments to study the impact of global warming in this fragile part of the world, and are becoming part of these skilled migrant labor communities in places like Utqiagvik, Alaska.

At its core, the Arctic’s human terrain will become increasingly indigenous but simultaneously complex, diverse, and globally interconnected.

These new demographic trends in a warming Arctic can present challenges for security and defense forces. At its core, the Arctic’s human terrain will become increasingly indigenous but simultaneously complex, diverse, and globally interconnected. Meaningful, genuine, and enduring civil-military partnerships with multiple populations and communities will need to be established as a pre-requisite for special operations forces operating above the Arctic Circle. Emergency assistance and disaster response operations will increasingly need to be provided from a multi-cultural standpoint and potentially in dozens of languages. Military planners and specialists in sociocultural intelligence will need to regularly analyze and understand the security implications of rapidly changing demographics in Arctic areas of operation where human traffickers, transnational criminal organizations, and foreign intelligence agents could sometimes operate in remote areas with limited oversight.

Despite these challenges, the U.S. military and other security organizations will likely find many more outstanding opportunities for enhanced partnerships with civilians in these rapidly changing communities. Establishing contractual relationships with local indigenous populations, tribal authorities, native corporations, and other such entities will become the central priority to operating in the Arctic, as they represent the original winter warriors in the northern polar region. Indigenous populations can assist the military as trainers, interpreters, remote area guides, bear patrol guards, and subject matter experts in numerous areas. Postsecondary tribal entities such as Ilisagvik College in Utqiagvik can provide online Inupiaq language and culture education for troops who will be operating in the U.S. Arctic, while the National Park Service’s Inupiat Heritage Center there can help coordinate talking circles and learning sessions with local elders on indigenous knowledge. Whaling captains can provide invaluable hunting and survival training to troops as well, as can many indigenous women who specialize in the skin sewing of traditional protective clothing and in understanding what local traditional medicinal and edible plants can be helpful in emergencies.

Even non-native groups that live in the U.S. Arctic can assist special operations forces with their planning and operations. Approximately 14% of Alaskans are veterans, the highest percent of any state in the nation, and they can assist as volunteer weather, cultural, climate change, coastal, and inland sensors and spotters. The growth in younger populations in the Arctic over time may also serve as a source of new recruits for various military and National Guard units. Many Samoans and other Pacific Islanders actively serve on local fire, emergency medical, and search teams in the Arctic and could partner with special operations forces on rescues, disaster response, and other crisis activities. Alaskan bush pilots are a wealth of knowledge on Arctic air logistics and northern polar meteorology, and can be found at local regional commuter terminals in Arctic towns. Similarly, Alaskan dogsled marathon mushers have a richness of Arctic wilderness survival skills to share, and reside in significant numbers in communities around Kotzebue in the Northwest Arctic Borough and Nome in Alaska. Alaska, which has the longest coastline of any state in the nation, also has thousands of fishermen scattered on boats throughout the region, and they can be a wealth of local knowledge on currents, maritime operations in extreme cold weather, changes in marine animal populations, and the presence of foreign vessels on the seas. Partnerships could also be established between special operations forces and Arctic local health facilities like hospitals, village health clinics, and the Alaska Community Health Aide program to leverage emergency medical service capabilities in remote areas during emergency organizations.

In sum, climate change is affecting more than just the ice pack and permafrost in the Far North. It is fundamentally reshaping the human populations that live in the region, and contributing to new demographic patterns with profound implications for special operations forces operating in the U.S. Arctic. It is time to break the ice and plunge into the messy melting pot of today’s culturally complex societies in the Arctic. The U.S. military cannot afford socially to be a sub-Arctic force that only visits communities above the 66th parallel during periodic training exercises. Indeed, special operation forces must now adopt a deeper understanding of environmental security from a social science perspective on the ground, in order to truly become one with the communities they are charged with serving in an evolving North.

Dr. Michele Devlin is Professor of Environmental Security at the U.S. Army War College. She coordinates the AWC Polar Bears, a student/faculty community of interest on Arctic environmental security issues. Dr. Devlin recently returned from spending six months living and working above the Arctic Circle on health and human security issues with indigenous families, climate migrants, remote villagers, and other unique populations residing in the U.S. High North.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

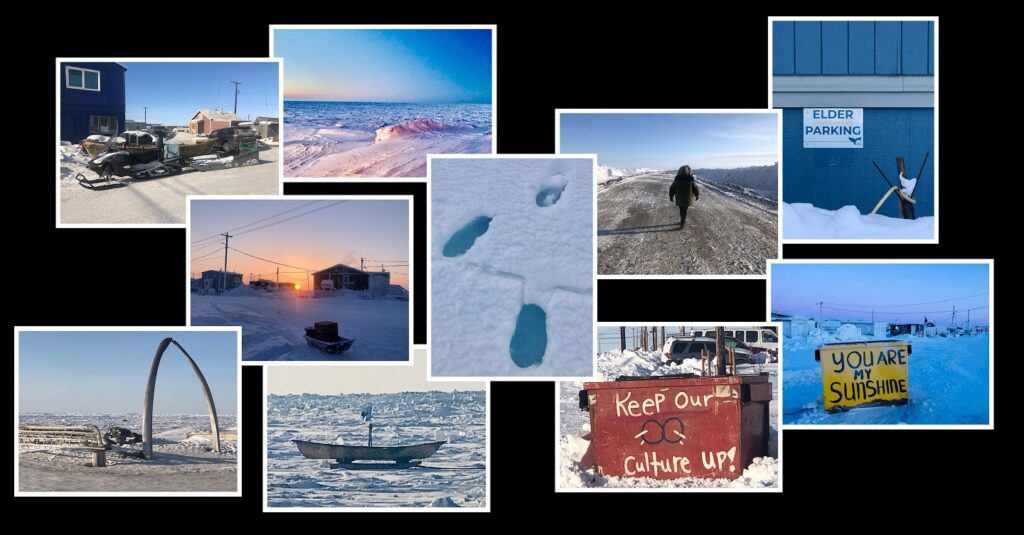

Photo Description: All photos are courtesy of the author taken during her travels in the Arctic region.