As he told a Marine officer a few days before he died, he wanted to be “where the action is.”

In the afternoon of February 27, 1967, the political scientist Bernard Fall was accompanying the 1st Battalion, 9th Marines, as it swept along one of the major roads in the northern portions of what was then South Vietnam. While the Marines sought out the Viet Cong, Fall, considered the West’s leading authority on Vietnam, dictated notes into a tape recorder as he walked along a rice-paddy dike: “Shadows are lengthening and we’ve reached one of our phase lines after the firefight and it smells bad — meaning it’s a little bit suspicious …. Could be an amb —.” These were his final words. He stepped on a landmine that killed both Fall and a nearby Marine.

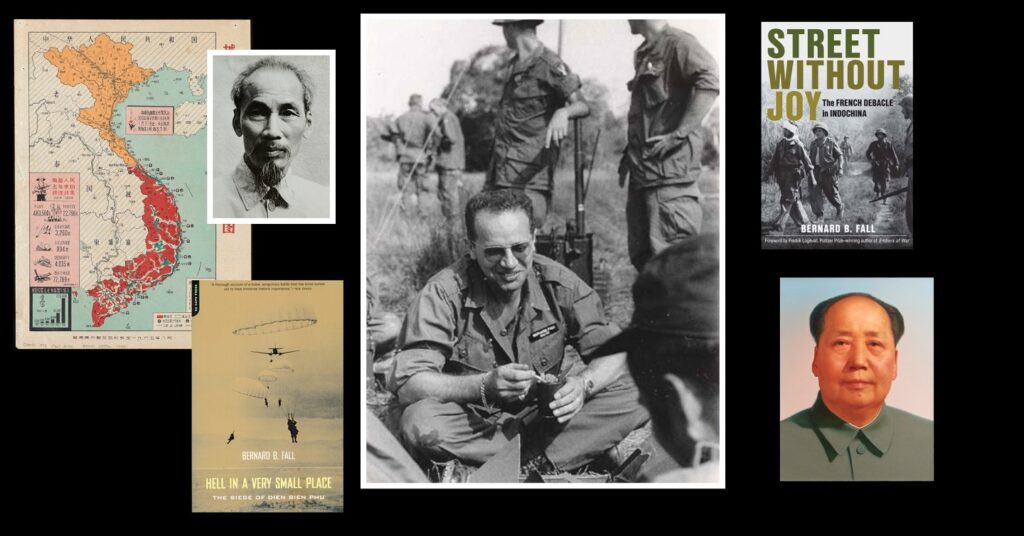

It was a dramatic end to a remarkably varied life. When he died, Fall was doing field work as a professor of government at Howard University, but prior to that he had fought in both the French resistance and Free French Army during World War II and authored two still admired books on the First Indochina War — Hell in a Very Small Place and Street Without Joy. His spouse, Dorothy Fall, paid tribute to him as a soldier-scholar, but Fall was also an award winning journalist with, articles that appeared in the New York Times Magazine, The Nation, The New Republic and Foreign Affairs.

However, Bernard Fall played a fourth role that is largely forgotten. He was a theorist of war; one who saw it from ground level. As he told a Marine officer a few days before he died, he wanted to be “where the action is.” He insisted on “experiencing the Vietnam War as the soldiers did.” For this, the U.S. military, officers and enlisted, revered him—read his books, invited him to lecture at its colleges, and published his articles in its professional journals. Fall understood that theory had three functions, as the military historian Peter Paret claimed in his essay on Clausewitz’s On War. Its purpose is not only cognitive and pedagogic, but also utilitarian. These are the three lenses through which Fall offered his theory of war.

Fall’s published writing on Vietnam, and Indochina in general, is prolific: studies and assessments of the politics, economics and security issues of the region covering a quarter century. His military analyses, in particular, exemplify a soldier’s understanding of strategy, operational concepts, and tactics, harnessed to a social scientist’s methodological approach—analysis based on fieldwork, interviews, government documents, and map/terrain analysis—along with a sound grasp of the relevant scholarly literature. Nonetheless, as military historian Lewis Bernstein pointed out, “the history of warfare is insignificant unless one knows what the fighting was about.” This understanding was evident in Fall’s work. He was writing intimately about what John Shy and Thomas W. Collier called revolutionary war. It is a phenomenon of the mid-20th century with its foundation in the theories of Mao Zedong, perhaps its most successful practitioner. It is a form of war that Vietnamese communist leaders Ho Chi Minh and Vo Nguyen Giap adapted to the Vietnamese context. Fall remains not only one of the most skilled interpreters of that adaptation, but he also offers an approach to its defeat—the theory and practice of counterinsurgency.

As scholar Nathaniel Mohr points out, while the counterinsurgency theories of French military officers Charles Lacheroy and others influenced Fall’s perspective, ultimately, their interest was in developing doctrine that could be applied to France’s war in Algeria. Fall had his own ideas, formed from his analysis of France’s defeat in Indochina. As a social scientist he was interested in understanding the underlying causes of insurgency, but as a theorist he sought to offer his military audience correctives. Thus, Fall first asked three fundamental questions about revolutionary war. What is the object of revolutionary war? How is revolutionary war fought? What constitutes victory in revolutionary war and how is it achieved?

The object of revolutionary war is a political aim. As Fall observed, “the Vietnam struggle is and always has been political: military operations are meaningless unless they have a political objective.” That political objective is “imposing and constructing a system of political control that is amenable to the victor’s interests.”

Thus, revolutionary war is fought as a politico-military effort with the military component based on Mao Zedong’s theory of protracted war, not to be confused with guerrilla warfare, which ultimately results in a sizable insurgent force that fights using the tactics and techniques of conventional warfare. It is a form of compound war. The political component consists of a shadow government that seeks “administrative control” of the population at the local level, which Fall likens to a “stranglehold,” but also includes subversion, terrorism, propaganda to change the allegiance of the peasantry (the people), and economic control through taxation.

Fall emphasized the importance of understanding the operational environment and the enemy’s concept of operations.

Moreover, revolutionary war recognizes the relationship between the political objective and the character of war: war is applied theory. Fall emphasized the importance of understanding the operational environment and the enemy’s concept of operations. With respect to the latter, Fall underscored comprehending the problem based on high-quality intelligence and the situation that a military force confronts in terms of enemy firepower, logistical support and terrain to include its impact on tactics. But strategic thinking counts too. “Versatility and imagination,” he wrote, matter more than advanced technology because war’s political end cannot be overshadowed by military means.

Victory is the result of success at all levels of war, but in particular at the tactical and operational level. In On Protracted War, Mao states: “This question of the political mobilization of the army and the people is indeed of the greatest importance. … There are, of course, many other conditions indispensable to victory, but political mobilization is the most fundamental.” It is won in the countryside (Indochina—a colonial and feudal society based on agriculture) and not in the cities. For Vietnam, as Fall points out, the lifeblood of French colonial Indochina is rice production. The urban areas must be cut off from the “hinterlands,” the “rice bowl,” and morale drained. However, that approach is not wholly sufficient, because in fighting a great power (“well-trained Western Army”), one must move from guerrilla warfare to large-scale operations. This means building a sizable force, the Vietnamese People’s Army, composed of infantry divisions, and undertaking a counteroffensive when decisive victory can be achieved which the Vietminh (the nationalist-communist united front) achieved at Dien Bien Phu in 1954, four years after Giap articulated his concept of operations. Fall also believed that victory resulted from the French high command’s “rigidity in tactical thinking,” lack of an “offensive spirit” and underestimation of an enemy that could nullify France’s “weapons monopoly.” In short, he asserted that the French command failed to understand the operational environment.

Thus, to fight revolutionary warfare and its character, Fall offers both a theory and practice of counterinsurgency. The principal aim, he underscores, is to defeat the insurgency before it can evolve into a large-scale war. He has a formula for this prescription: RW = G+P, that is, “revolutionary warfare equals guerrilla warfare plus political action.” Guerrilla warfare is used to establish a political system. He explains that the “revolutionary warfare operator” is not necessarily a communist. The operator can be any group that seeks, through competition to exert political control over a populace in “support of a doctrine” that finds support across socioeconomic classes. This control is administrative control: “When a country is being subverted it is not being outfought; it is being out-administered.” Thus, “conventional military factors are meaningless in that type of war.”

Beginning in the early 1950s, based on his on-the-ground observations, Fall stressed the criticality of political action, a variety of social, political and economic reforms, “as essential to success as ammunition for the howitzers,” to mitigate the grievances of the population and their prompt allegiance to their government. Moreover, Fall understood that in waging a counterinsurgency, success was incremental and that “normalcy” was relative. U.S. military and political leaders should not expect that it could attain “American normalcy.” Instead, the counterinsurgent has to determine and accept a “minimal acceptable background incident rate.” Nonetheless, Fall recognized that to succeed in attaining administrative control, security was a prerequisite. Security, he noted, requires a high degree of troop saturation, but even then, historical experience shows victory can be elusive—costly in human and financial resources. Recognizing this is equally essential. There is no “miracle cure” if underlying political, social and economic issues are not addressed. A million troops “could crush the opposition,” but, quoting the historian Tacitus on Rome’s conquest of Britain, the result would be: “They create desolation and call it peace.”

As a theorist of revolutionary war, Fall addresses all three of theory’s functions. First, the cognitive: he uses the past as a means of understanding the phenomenon of war. He defines it and structures an intellectual response to its reality, linking the past to the present thereby constructing conceptual frameworks. “War is a contest of intellect,” Army Doctrine Primer 1-01 points out. Second, Fall seeks to illuminate the individual’s comprehension of revolutionary war through the use of historical mindedness and social science methods. Here the focus is on the individual using history, experience and study to develop one’s own theory of war, the pedagogic. Lastly, theory’s utilitarian function is of limited direct value. As Fall pointed out that there are no “easy shortcuts in solving the problems of revolutionary war;” it demands new approaches and ideas be tried and judged. Theory serves to sharpen judgment of these approaches and ideas. It is a competence which is of particular use to the military leader and those who aspire to such a position that Bernard Fall—the academic, journalist, Soldier, and theorist astutely understood and communicated. Modern strategists would do well to rediscover the neglected wisdom of Bernard Fall.

Frank Jones is a former professor of security studies at the U.S. Army War College where he taught in the Department of National Security and Strategy. Previously, he had retired from the Office of the Secretary of Defense as a senior executive. He is the author or editor of three books and numerous articles on U.S. national security.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

Photo Description: Top Left – Ho Chi Minh; Center – Bernard Fall lunches with U.S. Army troops in Vietnam early 1967; Bottom Right – Mao Zedong: Chairman of the Communist Party of China

Photo Credit: Top Left- Unknown photographer circa 1946; Center – U.S. Army Photo, unknown photographer circa 1967; Bottom Right – portrait attributed to Zhang Zhenshi and a committee of artists; all via Wikimedia Commons