As he told a Marine officer a few days before he died, he wanted to be “where the action is.”

In the afternoon of February 27, 1967, the political scientist Bernard Fall was accompanying the 1st Battalion, 9th Marines, as it swept along one of the major roads in the northern portions of what was then South Vietnam. While the Marines sought out the Viet Cong, Fall, considered the West’s leading authority on Vietnam, dictated notes into a tape recorder as he walked along a rice-paddy dike: “Shadows are lengthening and we’ve reached one of our phase lines after the firefight and it smells bad — meaning it’s a little bit suspicious …. Could be an amb —.” These were his final words. He stepped on a landmine that killed both Fall and a nearby Marine.

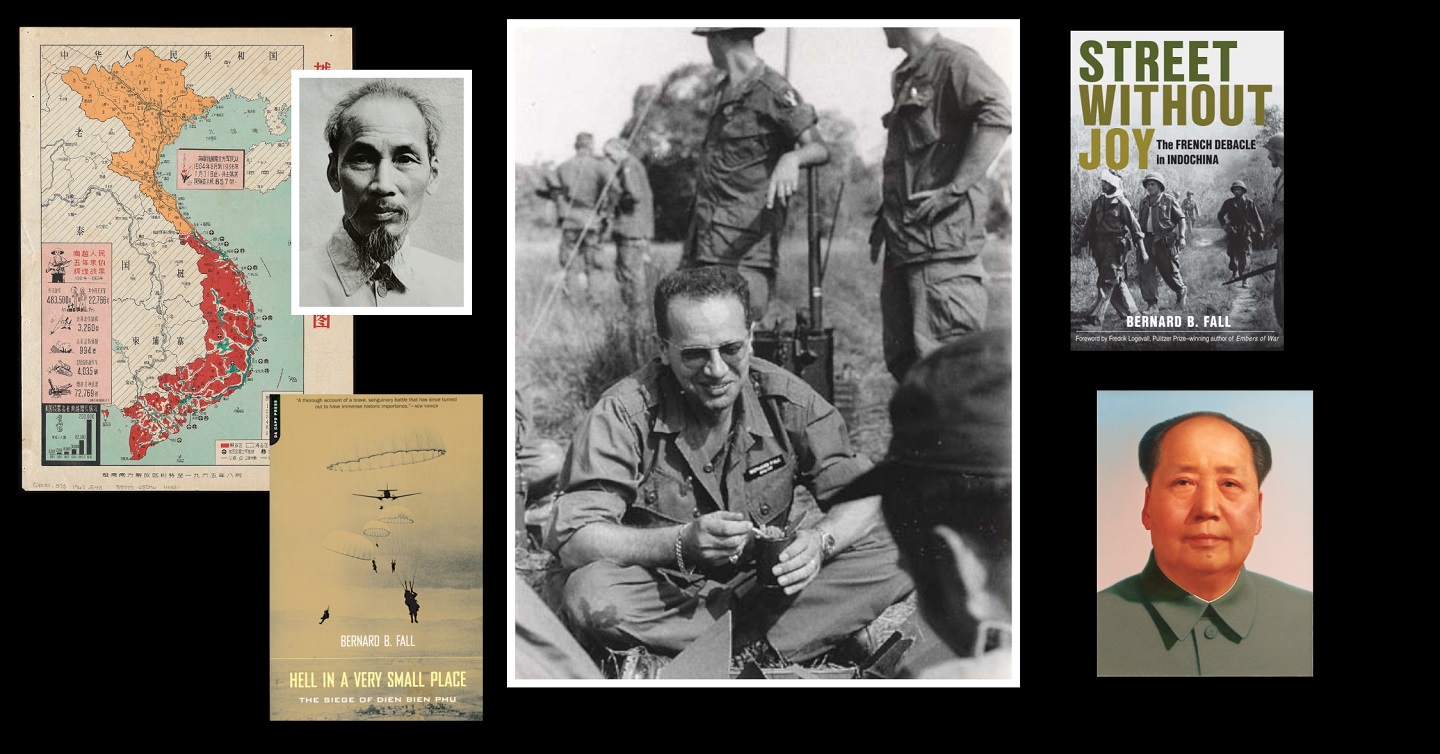

It was a dramatic end to a remarkably varied life. When he died, Fall was doing field work as a professor of government at Howard University, but prior to that he had fought in both the French resistance and Free French Army during World War II and authored two still admired books on the First Indochina War — Hell in a Very Small Place and Street Without Joy. His spouse, Dorothy Fall, paid tribute to him as a soldier-scholar, but Fall was also an award winning journalist with, articles that appeared in the New York Times Magazine, The Nation, The New Republic and Foreign Affairs.

However, Bernard Fall played a fourth role that is largely forgotten. He was a theorist of war; one who saw it from ground level. As he told a Marine officer a few days before he died, he wanted to be “where the action is.” He insisted on “experiencing the Vietnam War as the soldiers did.” For this, the U.S. military, officers and enlisted, revered him—read his books, invited him to lecture at its colleges, and published his articles in its professional journals. Fall understood that theory had three functions, as the military historian Peter Paret claimed in his essay on Clausewitz’s On War. Its purpose is not only cognitive and pedagogic, but also utilitarian. These are the three lenses through which Fall offered his theory of war.

Fall’s published writing on Vietnam, and Indochina in general, is prolific: studies and assessments of the politics, economics and security issues of the region covering a quarter century. His military analyses, in particular, exemplify a soldier’s understanding of strategy, operational concepts, and tactics, harnessed to a social scientist’s methodological approach—analysis based on fieldwork, interviews, government documents, and map/terrain analysis—along with a sound grasp of the relevant scholarly literature. Nonetheless, as military historian Lewis Bernstein pointed out, “the history of warfare is insignificant unless one knows what the fighting was about.” This understanding was evident in Fall’s work. He was writing intimately about what John Shy and Thomas W. Collier called revolutionary war. It is a phenomenon of the mid-20th century with its foundation in the theories of Mao Zedong, perhaps its most successful practitioner. It is a form of war that Vietnamese communist leaders Ho Chi Minh and Vo Nguyen Giap adapted to the Vietnamese context. Fall remains not only one of the most skilled interpreters of that adaptation, but he also offers an approach to its defeat—the theory and practice of counterinsurgency.

As scholar Nathaniel Mohr points out, while the counterinsurgency theories of French military officers Charles Lacheroy and others influenced Fall’s perspective, ultimately, their interest was in developing doctrine that could be applied to France’s war in Algeria. Fall had his own ideas, formed from his analysis of France’s defeat in Indochina. As a social scientist he was interested in understanding the underlying causes of insurgency, but as a theorist he sought to offer his military audience correctives. Thus, Fall first asked three fundamental questions about revolutionary war. What is the object of revolutionary war? How is revolutionary war fought? What constitutes victory in revolutionary war and how is it achieved?

The object of revolutionary war is a political aim. As Fall observed, “the Vietnam struggle is and always has been political: military operations are meaningless unless they have a political objective.” That political objective is “imposing and constructing a system of political control that is amenable to the victor’s interests.”

Thus, revolutionary war is fought as a politico-military effort with the military component based on Mao Zedong’s theory of protracted war, not to be confused with guerrilla warfare, which ultimately results in a sizable insurgent force that fights using the tactics and techniques of conventional warfare. It is a form of compound war. The political component consists of a shadow government that seeks “administrative control” of the population at the local level, which Fall likens to a “stranglehold,” but also includes subversion, terrorism, propaganda to change the allegiance of the peasantry (the people), and economic control through taxation.

Fall emphasized the importance of understanding the operational environment and the enemy’s concept of operations.

Moreover, revolutionary war recognizes the relationship between the political objective and the character of war: war is applied theory. Fall emphasized the importance of understanding the operational environment and the enemy’s concept of operations. With respect to the latter, Fall underscored comprehending the problem based on high-quality intelligence and the situation that a military force confronts in terms of enemy firepower, logistical support and terrain to include its impact on tactics. But strategic thinking counts too. “Versatility and imagination,” he wrote, matter more than advanced technology because war’s political end cannot be overshadowed by military means.

Victory is the result of success at all levels of war, but in particular at the tactical and operational level. In On Protracted War, Mao states: “This question of the political mobilization of the army and the people is indeed of the greatest importance. … There are, of course, many other conditions indispensable to victory, but political mobilization is the most fundamental.” It is won in the countryside (Indochina—a colonial and feudal society based on agriculture) and not in the cities. For Vietnam, as Fall points out, the lifeblood of French colonial Indochina is rice production. The urban areas must be cut off from the “hinterlands,” the “rice bowl,” and morale drained. However, that approach is not wholly sufficient, because in fighting a great power (“well-trained Western Army”), one must move from guerrilla warfare to large-scale operations. This means building a sizable force, the Vietnamese People’s Army, composed of infantry divisions, and undertaking a counteroffensive when decisive victory can be achieved which the Vietminh (the nationalist-communist united front) achieved at Dien Bien Phu in 1954, four years after Giap articulated his concept of operations. Fall also believed that victory resulted from the French high command’s “rigidity in tactical thinking,” lack of an “offensive spirit” and underestimation of an enemy that could nullify France’s “weapons monopoly.” In short, he asserted that the French command failed to understand the operational environment.

Thus, to fight revolutionary warfare and its character, Fall offers both a theory and practice of counterinsurgency. The principal aim, he underscores, is to defeat the insurgency before it can evolve into a large-scale war. He has a formula for this prescription: RW = G+P, that is, “revolutionary warfare equals guerrilla warfare plus political action.” Guerrilla warfare is used to establish a political system. He explains that the “revolutionary warfare operator” is not necessarily a communist. The operator can be any group that seeks, through competition to exert political control over a populace in “support of a doctrine” that finds support across socioeconomic classes. This control is administrative control: “When a country is being subverted it is not being outfought; it is being out-administered.” Thus, “conventional military factors are meaningless in that type of war.”

Beginning in the early 1950s, based on his on-the-ground observations, Fall stressed the criticality of political action, a variety of social, political and economic reforms, “as essential to success as ammunition for the howitzers,” to mitigate the grievances of the population and their prompt allegiance to their government. Moreover, Fall understood that in waging a counterinsurgency, success was incremental and that “normalcy” was relative. U.S. military and political leaders should not expect that it could attain “American normalcy.” Instead, the counterinsurgent has to determine and accept a “minimal acceptable background incident rate.” Nonetheless, Fall recognized that to succeed in attaining administrative control, security was a prerequisite. Security, he noted, requires a high degree of troop saturation, but even then, historical experience shows victory can be elusive—costly in human and financial resources. Recognizing this is equally essential. There is no “miracle cure” if underlying political, social and economic issues are not addressed. A million troops “could crush the opposition,” but, quoting the historian Tacitus on Rome’s conquest of Britain, the result would be: “They create desolation and call it peace.”

As a theorist of revolutionary war, Fall addresses all three of theory’s functions. First, the cognitive: he uses the past as a means of understanding the phenomenon of war. He defines it and structures an intellectual response to its reality, linking the past to the present thereby constructing conceptual frameworks. “War is a contest of intellect,” Army Doctrine Primer 1-01 points out. Second, Fall seeks to illuminate the individual’s comprehension of revolutionary war through the use of historical mindedness and social science methods. Here the focus is on the individual using history, experience and study to develop one’s own theory of war, the pedagogic. Lastly, theory’s utilitarian function is of limited direct value. As Fall pointed out that there are no “easy shortcuts in solving the problems of revolutionary war;” it demands new approaches and ideas be tried and judged. Theory serves to sharpen judgment of these approaches and ideas. It is a competence which is of particular use to the military leader and those who aspire to such a position that Bernard Fall—the academic, journalist, Soldier, and theorist astutely understood and communicated. Modern strategists would do well to rediscover the neglected wisdom of Bernard Fall.

Frank Jones is a former professor of security studies at the U.S. Army War College where he taught in the Department of National Security and Strategy. Previously, he had retired from the Office of the Secretary of Defense as a senior executive. He is the author or editor of three books and numerous articles on U.S. national security.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

Photo Description: Top Left – Ho Chi Minh; Center – Bernard Fall lunches with U.S. Army troops in Vietnam early 1967; Bottom Right – Mao Zedong: Chairman of the Communist Party of China

Photo Credit: Top Left- Unknown photographer circa 1946; Center – U.S. Army Photo, unknown photographer circa 1967; Bottom Right – portrait attributed to Zhang Zhenshi and a committee of artists; all via Wikimedia Commons

Hey there, I just read your post on Bernard Fall and I have to say it’s a fascinating look into the life of a true soldier-scholar. I particularly appreciated the emphasis on his role as a war theorist from ground level. It’s clear that Fall was someone who truly wanted to understand war and the Vietnam War in particular, from the perspective of the soldiers on the frontlines. His dedication to “experiencing the Vietnam War as the soldiers did” is something that I think is often missing in discussions of war and conflict.

I also found it really interesting to learn about Fall’s approach to counterinsurgency. His emphasis on understanding the operating environment and the enemy’s ideology is something that I think is still incredibly relevant today. It’s clear that Fall was someone who not only studied insurgency but also had a real understanding of the political and economic factors that drive it. I think his emphasis on the importance of “imposing and building a system of political control acceptable to the victor’s interests” is something that is often overlooked in discussions of counterinsurgency.

Best regards, Mark Green of Jpazamu.com

From our article above:

” ‘The object of revolutionary war is a political aim.’ As Fall observed, ‘the Vietnam struggle is and always has been political: military operations are meaningless unless they have a political objective.’ That political objective is ‘imposing and constructing a system of political control that is amenable to the victor’s interests.’ ”

As to this such understanding of “revolutionary war,” consider the following contemporary observations of David Kilcullen and Robert Egnell:

“Politically, in many cases today, the counter-insurgent (the U.S./the West and its partner governments) represents revolutionary change, while the insurgent fights to preserve the status quo of ungoverned spaces, or to repel an occupier – a political relationship opposite to that envisaged in classical counter-insurgency. Pakistan’s campaign in Waziristan since 2003 exemplifies this. The enemy includes al-Qaeda-linked extremists and Taliban, but also local tribesmen fighting to preserve their traditional culture against twenty-first-century encroachment. The problem of weaning these fighters away from extremist sponsors, while simultaneously supporting modernisation, does somewhat resemble pacification in traditional counter-insurgency. But it also echoes colonial campaigns, and includes entirely new elements arising from the effects of globalisation.” (Item in parenthesis above is mine. See David Kilcullen’s “Counterinsurgency Redux.”)

“Dhofar, El Savador and the Philippines are all campaigns driven by fundamentally conservative concerns. When we are looking to Syria right now, (however,) it is not just about maintaining order or even the regime, but about larger political change. In Afghanistan and Iraq too, we represented revolutionary change. So, perhaps we should read Mao and Che Guevara instead of Thompson in order to find the appropriate lessons of how to achieve large-scale societal change through limited means? That is what we are after, in the end. And in this coming era, where we are pivoting away from large-scale interventions and state-building projects, but not from our fairly grand political ambitions, it may be worth exploring how insurgents do more with little; how they approach irregular warfare, and reach their objectives indirectly.” (Item in parenthesis above is mine. See the Small Wars Journal article “Learning From Today’s Crisis of Counterinsurgency” — an interview by Octavian Manea of Dr. David H. Ucko and Dr. Robert Egnell.)

Question — Based on the Above:

If Bernard Fall were alive and writing today, would he see “revolutionary war” — today — from much the same “the U.S./the West are the revolutionaries now” perspective suggested by Kilcullen and Egnell above?

This given, as Kilcullen and Egnell point out above, that it has been the U.S/the West, both at home and abroad and in the name of such things as globalization post-the Cold War, that has sought to “impose and construct a system of political control that is amenable to (the Cold War) victor’s interests?’”

“Since the 1990s the focus of American international security policy has been focused on creating conditions for extending zones of security and prosperity to other states under the theory that ‘political as well as economic globalization would make the world safer — and more profitable — for the United States.’ Consequently, the United States saw expansion, rather than retraction, of American military presence around the world.” (See the 2016 edition of the book “Exporting Security: International Engagement, Security Cooperation, and the Changing Face of the US Military” by U.S. Naval War College Professor Derek S. Reveron; therein, see the bottom of Page 2 of the Introduction chapter.)

From the information that I provide above, one can see the distinction/the difference between:

a. The “revolutionary”/the political, economic, social and/or value “transformative” attempts being made by (a) “progressive” native populations against (b) their status quo-loving-and-fighting-for colonial governments. (These being Bernard Fall’s “mid-20th Century” revolutionary wars?) And:

b. The “revolutionary”/the political, economic, social and/or value “transformative” attempts being made by (a) “progressive” governments against (b) their status-quo-loving-and-fighting-for native populations. (See Kilcullen and Egnell above.) (These being the — both before and after mid-20th Century “revolutionary wars” — such as we are witnessing both here at home and there abroad again today?)

Note that Kilcullen (see my second comment above) seems to compare the U.S./the West’s — and our partner governments — activities, in places such as Afghanistan post-the Old Cold War, to “colonial campaigns;” “campaigns,” thus, which were/are designed to overcome the “cultural backwardness” problems (lack of a Western “capitalism, markets and trade”-supporting political, economic, social and value orientation?) of the outlying states and societies of the world.

As to this such (both before and after the mid-20th Century?) political objective of the U.S./the West, consider Joseph Schumpeter’s thoughts below:

“Where the cultural backwardness of a region makes normal economic intercourse dependent on colonization, it does not matter, assuming free trade, which of the ‘civilized’ nations undertakes the task of colonization.” (See the first paragraph of Joseph Schumpeter’s 1919 “State Imperialism and Capitalism.”)

Question — Based on the Above:

Does Kilcullen’s such observations, above, suggest that — today — we might need to study the “small wars” addressed by, for example, C.E. Callwall; this, rather than the — mid-20th Century — “small wars” addressed by Bernard Fall?:

“Small wars are a heritage of extended empire, a certain epilogue to encroachments into lands beyond the confines of existing civilization and this has been so from the early ages to the present time. The great nation which seeks expansion in remote quarters of the globe must accept the consequences. Small wars dog the footsteps of ‘the pioneers of civilization’ in the regions afar off.” (The quotes around ‘the pioneers of civilization’ above are mine. See Chapter II — “the Causes of Small Wars” — in C.E. Callwell’s book “Small Wars: Their Principles and Practices.)

How might Fall’s theories be applied to the current Ukraine-Russian conflict?

As to the question asked by J F Carter above, might we consider the following?:

“Over the last fifty years, a lack of analysis on Bernard B. Fall (1926-1967) and his scholarship has been a significant gap in the historiography on the First Indochina War (1946-1954) and the Second Indochina War (1955-1975). Since the Vietnam War ended, the failure to recognize how military force cannot compensate for the lack of a politically attainable goal remains prevalent. As Fall once remarked, “A U.S. Marine can fly a helicopter better than anyone else, but he cannot give a Vietnamese farmer an ideology to believe in.” In much the same way, a Russian pilot will not be able to convince Ukrainians that political reconciliation is possible. Rather, Russia’s unprovoked invasion has made its political legitimacy impossible to maintain with every passing day that Russia continues to destroy the Ukrainian people and their country.

(See the International Institute of Asian Studies Newsletter 92, Summer 2022; therein, see the article “Bernard Fall: A Soldier of War in Europe, A Scholar of War in Asia, by Nathaniel L. Moir, Ph.D., a research associate in the Applied History Project at the John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University and the author of the book “Number One Realist – Bernard Fall and Vietnamese Revolutionary Warfare.”)

It is great to see this article in print and it is positive to see increased interest in Bernard Fall’s life and prodigious scholarship. I would like to point out that a book I wrote, Number One Realist: Bernard Fall and Vietnamese Revolutionary Warfare, published by Hurst and Oxford University Press in April 2022, goes into depth about Fall’s ideas on Revolutionary Warfare. It also investigates how he envisioned this approach to warfare in the context of Indochina and how his experiences during World War II shaped his views. It is important to note that the author of this article does not discuss Fall’s work as a research analyst during the Nuremberg Tribunals (as a translator during the first series of tribunals, the IMT) and as a researcher focused on the Krupp Corporation’s use of slave labor – mostly women and children from Hungary/Czechoslovakia, Ukraine, and elsewhere – during the NMT series of tribunals overseen by the US and led by prosecutor Telford Taylor.

Fall’s experience at Nuremberg was highly significant because it revealed a deeply, although secularized, element in his writing and judgments about the legality of warfare and why “rules of war” should be followed. In short, he condemned the Viet Minh/NLF, particularly disastrous land reform policies and others, as much as French and U.S. over-militarized approaches that violated laws of warfare. His relentless interest in pointing out violations of laws of war may partially explain why he was marginalized by some in the JFK/Johnson administrations. This certainly became the case as he became increasingly critical of US involvement in Southeast Asia. It is worthwhile, however, to note that individuals, such as Senator J. William Fulbright admired and often met with Fall and these interactions led to Fulbright’s Vietnam Hearings in 1966. At the same time, Fall remained a full professor at Howard University and his students included, for example, Stokely Carmichael. Carmichael, writing as Kwame Ture, pointed out in “Stokely Speaks” how Fall influenced him. It is to Fall’s credit that he could work and influence individuals as divergent as Fulbright and Carmichael.

Finally, this article is to be commended in that the author points to some highlights about Fall’s career that made his worthy of study for an entire book, mentioned earlier, that I hope the author and others might consider for an in-depth look at Fall’s life and career.

Great article and it is positive to see others writing informed work about Bernard Fall.

War theorists are important, especially since the cause of war is unknown, and the Doomsday Clock is 90 seconds to midnight.

“Shadows are lengthening and we’ve reached one of our phase lines after the firefight and it smells bad — meaning it’s a little bit suspicious …. Could be an amb —.” These were his final words. He stepped on a landmine that killed both Fall and a nearby Marine.

It is interesting Fall had a premonition just before he died. Many people have experienced this. Some from feelings, and some from repeated overt warnings from other people like in the recent loss of the Titanic submersible, or a near miss in a high hazard industry, that may or may not be heeded. I wonder if populations also get premonitions, or warnings about future events.

For example, if the current war in Ukraine does not spin out of control, then it is a near miss. Will we heed the “warning”? If so, and do what? One thing that can be done is dialogue about different theories of conflict such as happened here.

One theory I am concerned about that is also rarely discussed and mentioned in only a few discussions of some papers that mention this theory as a possibility, is “the forest fire model of war”. There is not even a review article on the model and it is not mentioned in textbooks on “the cause of war”. The model comes from Lewis Fry Richardson’s discovery that war casualties as a function of war frequency follows a power law distribution, just like forest fires and earthquakes. This means an unknown stressor, or fuel in the forest, builds up over time in society until Kaboom, global war. Since world war has started in the first quarter of the last two centuries, the current war in Ukraine with repeated nuclear threats is right on time.

The model both confirms the current setting of the Doomsday Clock, and offers new options to “reset the clock”. That is because there are systems that accumulate tension to failure, and have been defused. Unfortunately, these systems have not been discussed in international relations.

Perhaps, if we heed the premonitions, feelings, and overt warnings, then that discussion can begin before the next Kaboom.