Peacetime military thinking is often isolated from the refining forces that arise from real, immediate competition.

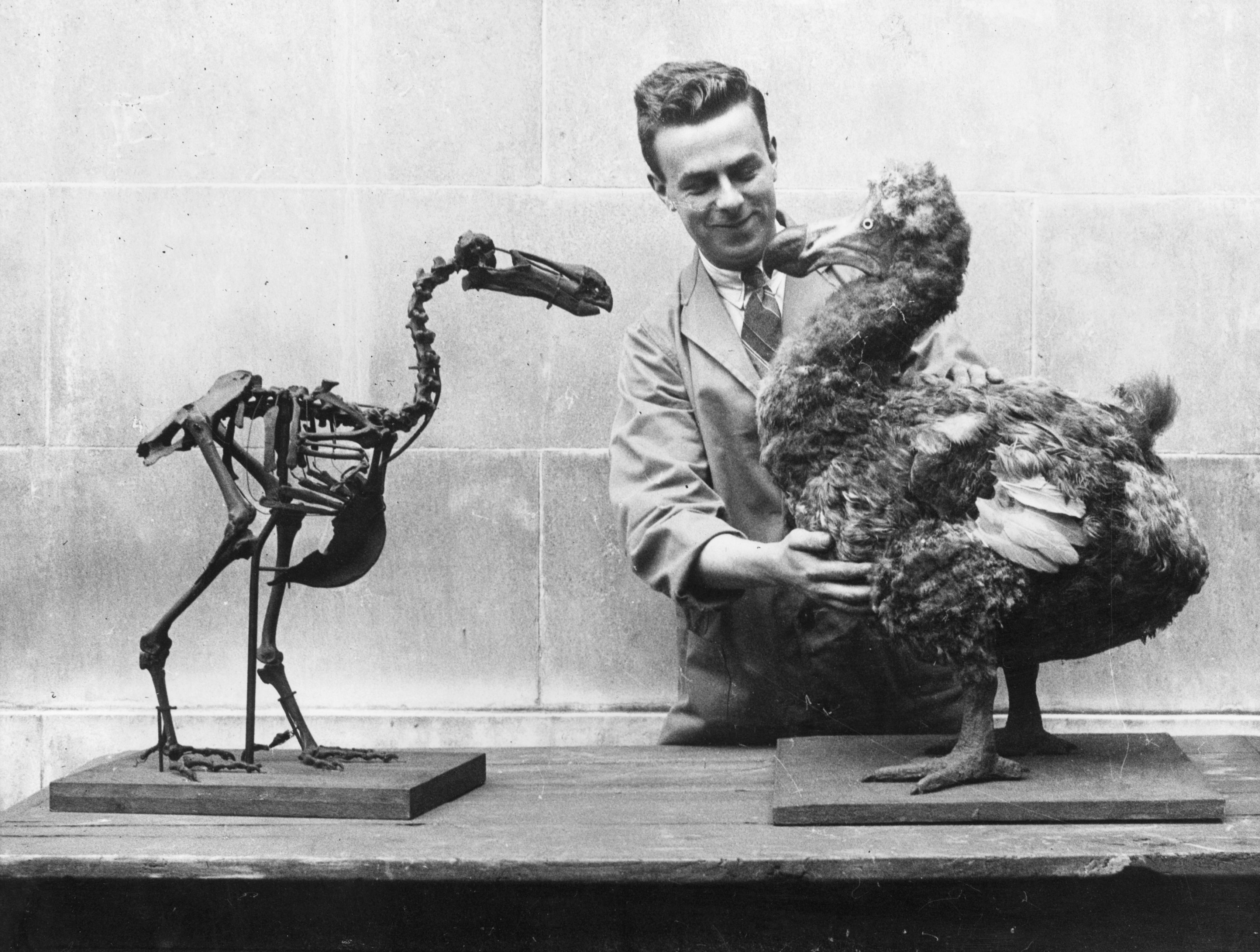

Millions of years ago, ancient pigeons flew from their southeast-Asian home and settled on islands scattered across the Indian Ocean. Some of the birds eventually landed on Mauritius, a volcanic island east of Madagascar. For thousands of millenia, they lived on the island’s fruit, seeds, and nuts. The birds changed significantly during that time. Without the threat of ground-based predators, the main competition for food was other members of their own species. Wings were of little value, and the birds evolved large bodies, strong and fast legs, and big beaks — useful for fighting and for cracking open tough seeds and nuts. At some point, the birds stopped flying altogether. Yet they continued to survive and thrive, co-evolving with the island’s other flora and fauna.

In 1598, Dutch sailors arrived on Mauritius. The birds did not fear humans and proved easy prey, but the real threats were human deforestation of the island and the animals that the sailors introduced to the island’s ecosystem — pigs, monkeys, and dogs that feasted on eggs in the birds’ unprotected nests. Within eighty years, these flightless birds — known to us as dodos — were extinct.

We think of the dodo as a weak and stupid creature, unfit for a harsh world. Yet it was eminently suited to the survival requirements of its environment, and became what it was through the same processes of mutation and competitive selection that have shaped the development of all life on earth. The dodo’s problem was its isolation from the extreme competitive dynamics of continental ecosystems; it had no effective response to creatures that were formed in those harsh systems. There is a lesson here.

Our ideas about the world exist in a sort of evolutionary system of theories that continually applies competitive pressures, driving weak ideas to extinction, and improving the fitness of those that survive. From this notion of an ecosystem of theories, it follows that ideas that are subject to strong competition will usually be more reliable and “fit” in an evolutionary sense than those that persist with limited (or no) challenges to their validity. Competition waxes and wanes, and bad ideas can persist for some time, but weak ideas eventually succumb to an accumulation of inconvenient facts. This is true of scientific theories, and theories of business competition. It is also true of our ideas about warfare.

We need strong, open competition in military thinking, and professional military education has a crucial role in fostering an environment that encourages it.

Theories of war may be uniquely susceptible to the dodo’s problem. Unlike science and business, military thinking usually occurs outside of the context that it seeks to understand. Williamson Murray observed, “Military organizations can rarely replicate in times of peace the actual conditions of war… There is no other profession in the world whose peacetime efforts represent only a pale shadow of the harsh realities in which its men and women must carry out their true functions.” Peacetime military thinking is often isolated from the refining forces that arise from real, immediate competition. Professional, bureaucratic, and political factors form conceptual oceans that may distance key military concepts from broad, rigorous intellectual scrutiny. On their island of intellectual evolution, peacetime military ideas evolve through internal competition, and seem strong and fit until the Dutch sailors show up.

The genesis of War Room is the idea that more opposition in the ecosystem of military ideas is always good. We need strong, open competition in military thinking, and professional military education has a crucial role in fostering an environment that encourages it. The nation’s senior military colleges (the Army, Navy, Air, and Marine War Colleges, and National Defense University) should be the locus of aggressive, open challenges to orthodox thinking in national security and defense. They can exercise great influence through their pursuit of knowledge free of the limitations (and occasional threats of retribution) that constrain inquiry in organizations with more tangible forms of power. The real mission of these institutions is to enable free and open inquiry in the areas of national security and defense. This requires a commitment to two core principles.

First, no idea is sacred, and nothing is settled. In the Logic of Scientific Discovery, Karl Popper wrote, “The game of science is, in principle, without end. He who decides one day that scientific statements do not call for any further test, and that they can be regarded as finally verified, retires from the game.” This need for continued testing is even more pronounced in areas of human competition, where all assumptions are provisional.

Second, there are no entry requirements to participate in the conversation. The military easily erects barriers to join the debate. One must be a member of the profession of arms, have experience in past conflicts, access to classified material, or time in relevant organizations or positions. This is understandable, but misguided. From Archimedes, to Genghis Khan, to Joan of Arc, history has shown that outsiders have the capacity to challenge and transform how we think about and conduct war. We have much to gain from broadening participation in strategic dialogue.

Let us avoid the dodo’s fate: by subjecting our ideas to healthy competition during peace, we will be better prepared to prevail in war.

We hope that you join us in War Room.

Andrew A. Hill is the Editor-in-Chief of War Room and a Professor at the U.S. Army War College. The views in this article are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army or U.S. Government.

Photo: Becker/Fox Photos/Getty Images

Andrew, Congrats form Athens!