Since the interwar period, the U.S. Army has sought to gain advantages over adversarial forces and potential enemies via new weapons, armaments, methods of fighting and methods of organizing for fighting.

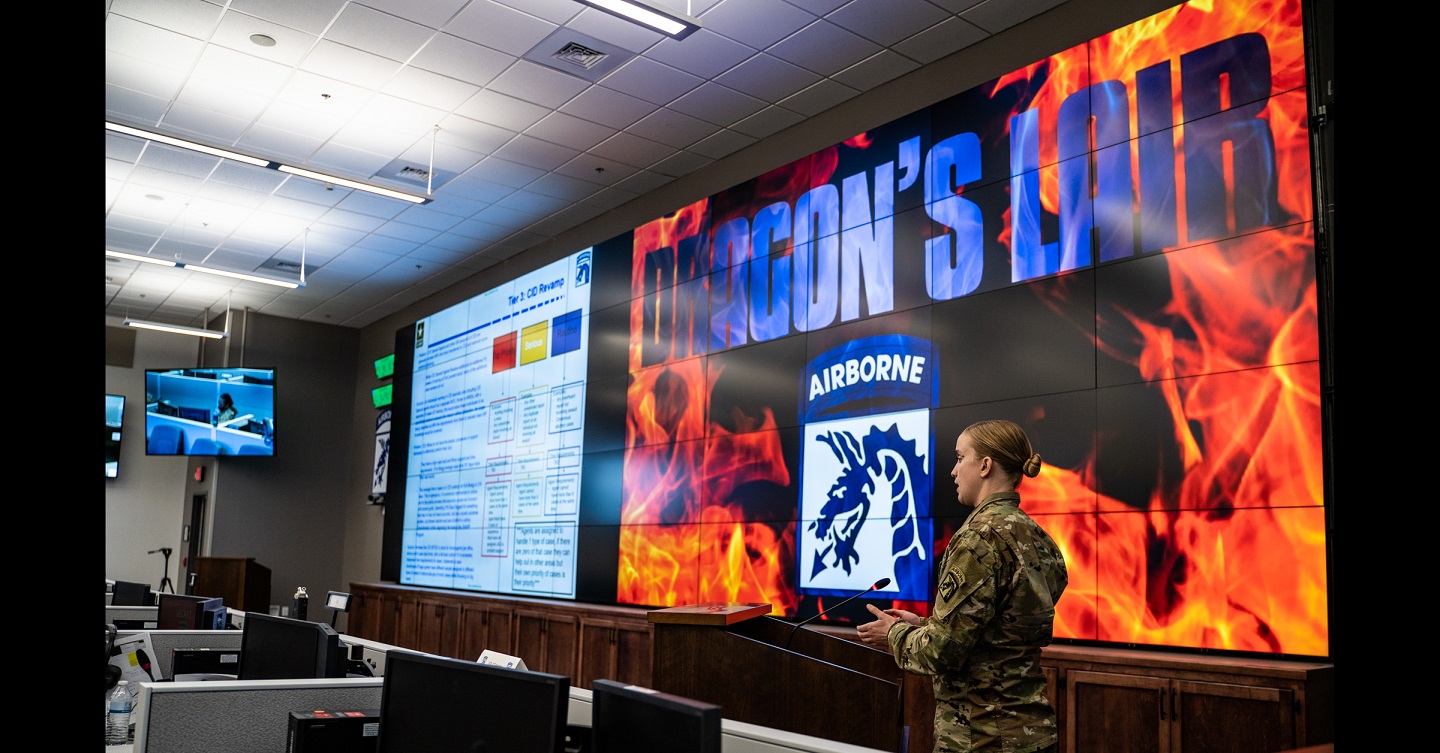

Dragon’s Lair, a new program that the U.S. Army’s XVIII Airborne Corps introduced in August 2020, seeks to coax new ideas into the light to improve all aspects of land power through a publicly promoted contest. The program is partly theater – Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson, who likely is unfamiliar with Army procurement, promoted Dragon’s Lair for the Corps on Twitter, and each iteration is referred to as an “episode,” seeking to replicate the NBC reality show “Shark Tank.” This theater, however, is in service of the larger goal of shining a spotlight on Soldier innovation. Dragon’s Lair is focused on creating an innovative culture across all echelons, ranks and formations, and generating awareness of the program is key to the long-term success of Soldier-led innovation.

While Dragon’s Lair is a new initiative, Army innovation is not. Since the interwar period, the U.S. Army has sought to gain advantages over adversarial forces and potential enemies via new weapons, armaments, methods of fighting and methods of organizing for fighting. After World War II, in particular, the service sought revolutionary change in every corner of Army life. From large-scale reinvention of combat maneuver exemplified by the airmobile concept developed by the Army Operations Office in the late 1950s, to quality of life upgrades such as the development of private barracks rooms to accommodate the All-Volunteer Force in the early 1970s, America’s land power service has long sought improvement in all areas related to military service. This tradition continues today as the Army encourages innovation across all echelons.

The Tragedy and Promise of Trapped Innovation

The United States’ ability to keep pace with change and to maintain an advantage over global competitors depends on the diversity of culture, thought, and social experiences within the Army’s community. However, the traditional Army structure can stifle innovation born out of diversity, with Soldier-driven ideas trapped within formations with no mechanism to surface. Harnessing this potential requires a culture wherein leaders seek solutions to daily challenges from soldiers of all ranks. It requires providing a platform for Soldiers to introduce their ideas to the command and then encouraging and uplifting those ideas. It also requires mature leaders who have the confidence to plow through traditional bureaucratic systems to bring a new idea to fruition.

Military units are disadvantaged by slow official processes when designing and incorporating new ideas, systems and technologies. Unseen change occurs daily at the Army’s lowest levels as troops quietly improve systems and processes. Soldiers identify and solve inefficiencies in their daily operations, implementing change as they do. Pulling those changes up to the top allows good ideas to flow throughout a large organization. Dragon’s Lair seeks to do exactly this, crowdsourcing ideas to improve the force.

A New Program Birthed by a Sprawling Army Command

The XVIII Airborne Corps’ Dragon’s Lair program is a competition whereby Soldiers present their innovations to a panel of experts and commanders. The Corps leadership awards the Soldier with a school of their choice and agrees to implement the winning ideas as deeply across the entire organization as possible. In this effort, the ground floor serves as the point of entry for new ideas. While the Army has venues for Soldier-driven ideas such as the Interactive Customer Evaluation system and the Army Ideas for Innovation Program, these platforms have no centralized awards process and inputs are not publicly displayed. Submissions to Dragon’s Lair, on the other hand, are viewable by all Soldiers, and the program ensures a consistent promotion and awards platform.

Given the moniker “Dragon Corps” in World War II due to its Welsh basilisk insignia design, the XVIII Airborne Corps is a colossus: it is about one-fifth of the active Army. Headquartered on Fort Bragg, North Carolina, the 92,000-Soldier organization is spread throughout 14 major North American installations and is a varied mixture of armor, mechanized infantry, aviation, light infantry, air assault and airborne. With that mixture of forces comes a varied set of experiences and military occupational specialties. Those experiences and specialties represent possible insights and solutions gained in daily service as troops adapt to overcome stale processes. However, the traditions of military hierarchy, the bureaucracy of Department of Defense budgeting and procurement processes and the enormity of the Army itself all work against a broader implementation of these ideas across the force.

The organizing principle behind Dragon’s Lair is that American Soldiers, in the fulfillment of their daily duties, identify inefficiencies unseen by the broader force. This is particularly so with a highly specialized Army, one formed around multi-domain operations.

While this process does create a new bureaucracy to sort and adjudicate submissions, it circumvents all layers of command in between the Soldier and the commander’s hand-picked team of screening experts.

A Program Focused on Beating Bureaucracy

The sole point of entry into Dragon’s Lair is a website accessible to anyone in the organization wherein Soldiers may submit their ideas. Critical to the program is that the website eliminates all barriers between idea and command. The commander of the Corps, Lieutenant General Erik Kurilla, personally reviews each new entry. The website submission process creates a conduit between Soldier and commander, effectively bypassing the challenges posed by chain-of-command and bureaucratic staffing processes.

The commander first reviews each idea, and then a subject matter expert within the field of consideration does so. They select five ideas for Dragon’s Lair, but those unselected remain in consideration for implementation. The program website allows users to comment and provide recommendations on each submission, and the team of subject matter experts provides additional considerations where appropriate. While this process does create a new bureaucracy to sort and adjudicate submissions, it circumvents all layers of command in between the Soldier and the commander’s hand-picked team of screening experts.

The finalists move on to the Dragon’s Lair competition during which the innovator presents his or her idea to a panel of civilian technical experts and members of the Corps senior leadership. Each innovator has 10 minutes to describe the innovation and the problem it addresses. Another 20 minutes are allocated for a discussion between the innovator and the panel. The panel then votes on each submission with each member receiving an equitable share of the vote.

The Way Ahead

Since its inaugural episode in October 2020, Dragon’s Lair has included concepts such as unmanned surveillance aircraft for subterranean environments, a mobile application to improve tracking of supplies and hand receipts, and an image-hosting website for collection, storage, and classification of historic photos. The long-term credibility of the program requires that at least some of the innovations are brought to market and effectively implemented across the force. The XVIII Airborne Corps leadership is coordinating with Department of Defense agencies to fund the implementation of the winning innovations. While Dragon’s Lair is limited by the lack of a reliable funding source for winning innovations, the Corps leadership seeks implementation through existing operational budget streams and external U.S. Department of Defense agencies.

Even this early, the program shows promising signs. Parallel U.S. Army organizations such as III Corps and the Maneuver Center of Excellence have initiated their own Dragon’s Lair programs. The U.S. Army’s Futures Command, the custodian command for all Army modernization, is coordinating implementation of the first winning Dragon’s Lair idea: a mobile application for organizing and coordinating gun ranges and training land across the U.S. Army. A prototype application is set for release in 2021. Meanwhile, the XVIII Airborne Corps is aggressively seeking a pathway to implement new technologies developed through Dragon’s Lair, particularly those not requiring new funding. More than a dozen Dragon’s Lair submissions, to include those not selected for presentation in the program, are in various stages of implementation.

The Coming Revolution

Army modernization efforts must begin at the top with a command focus on grand innovation through leadership, encouragement, and communication. Such programs, however, can be more powerful if they reach down to the lowest level of the organization to solicit crowdsourced input for broad organizational changes. In fact, this kind of innovation, long a part of the Army’s lifeblood, is critical to profitability sustainment in the corporate world. In uplifting, supporting, and funding Soldier-led concepts, military commands may harness the true power of the idea.

Recent Dragon’s Lair episodes have moved from tech-based combat solutions to cultural and social Army issues. For example, a recent winning solution proposes a mobile application for centralization of information and resources for Soldiers with special-needs family members. The app is in development within the Corps headquarters. Another recent episode focused on solutions to the scourge of sexual assaults and sexual harassment incidents plaguing the force. Future episodes will continue to expand the program out across the full breadth of life across the Army. In so doing, Dragon’s Lair may prove to drive evolution of the Nation’s land-based military service well into the future, a future made better by Soldier innovation.

Joe Buccino is a U.S. Army Colonel and the Communications Director for the U.S. Army’s XVIII Airborne Corps on Fort Bragg, North Carolina. He is a graduate of the AY20 Resident Class of the U.S. Army War College. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

Photo Description: 1st Lieutenant Alexandra R. Elison, a Military Police Officer with the U.S. Army’s XVIII Airborne Corps, presents her idea for a mobile application for revised reporting procedures for allegations of sexual assault and sexual harassment across the force at episode 4 of Dragon’s Lair at the XVIII Airborne Corps Headquarters on Fort Bragg, NC, February 22, 2021.

Photo Credit: U.S. Army Sergeant Mary Barnes, XVIII Airborne Corps.

Possibly the readers of the “Dragon’s Lair” (etc.) would like to take on, and suggest how best to deal with, the following contemporary problem — a problem which, as we will shall see later in this comment, directly effects our military personnel today — this such contemporary problem to be understood as follows:

The U.S./the West, post-the Old Cold War, came to view “international competition” — and thus success relating to same — more in economic terms. Thus, the U.S./the West, at that time, came view the need to overcome the U.S./the West’s “cultural backwardness” problems such as sexism and racism, etc. (which are said to significantly hinder/harm not only a nation’s legitimacy but also its economic growth potential) as now being a mandatory “national security” requirements.

Here is an example of this such thinking — in this case — as relates to (novel?) decisions then being made by the U.S. Supreme Court:

“Even more telling than its use of elite opinion in ‘Lawrence’ was the Court’s unembarrassed reliance on elite views to determine the scope of a highly contested constitutional anti-discrimination norm in ‘Grutter.” Relying extensively on amicus briefs submitted by elite corporate, military, and educational authorities, Justice O’Conner, writing for the majority, asserted the following:

“Major American businesses have made clear that the skills needed in today’s increasingly global marketplace can only be developed through exposure to widely diverse people, cultures, ideas, and viewpoints. What is more, high-ranking retired officers and civilian leaders of the United States military assert that ‘[based on their] decades of experience,’ a ‘highly qualified, racially diverse officer corps … is essential to the military’s ability to fulfill its principle mission to provide national security.’ …”

“In short, the Court based its constitutional reasoning on the contention of a group of the Nation’s key corporate, political, and military leaders that the Nation’s prospects of success in the face of international strategic threats, as well as continued stability and perceived legitimacy in its domestic political institutions, required racial preferences in elite formation through our major educational institutions.”

(See the Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law paper entitled: “Moral Communities or a Market State: The Supreme Court’s Vision of the Police Power in the Age of Globalization,” by Antonio F. Perez and Robert J. Delahunty. See pages 698 and 699.)

Of late, however, there as been a “cultural backlash” against these such “progressive” — but above-described as “national security-required” — moves.

Bottom Line Question — For the Readers of the “Dragaon’s Lair” (etc.):

Might we agree — based on my explanations above — that certain of our U.S./Western military personnel today are now caught in the “crosshairs” of this such conflict. Herein, being asked to choose between (a) national security and (b) cultural security?

(And, herein, our opponents today, such as Russia, telling our soldiers — in no uncertain terms — to choose “cultural security:”

“Liberal democratic societies have, in the past few decades, undergone a series of revolutionary changes in their social and political life, which are not to the taste of all their citizens. For many of those, who might be called social conservatives, Russia has become a more agreeable society, at least in principle, than those they live in. Communist Westerners used to speak of the Soviet Union as the pioneer society of a brighter future for all. Now, the rightwing nationalists of Europe and North America admire Russia and its leader for cleaving to the past.”

[See “The American Interest” article “The Reality of Russian Soft Power” by John Lloyd and Daria Litinova.]

“Compounding it all, Russia’s dictator has achieved all of this while creating sympathy in elements of the Right that mirrors the sympathy the Soviet Union achieved in elements of the Left. In other words, Putin is expanding Russian power and influence while mounting a cultural critique that resonates with some American audiences, casting himself as a defender of Christian civilization against Islam and the godless, decadent West.”

[See the “National Review” item entitled: “How Russia Wins” by David French.])

This study investigates how human security manifests itself in the context of Afghanistan and explores the factors that promote and impede its development. It is time to reframe how America views the mission in Afghanistan, and history can help. One must reframe the problem in the context of the new guidance.

From our article above (in the section entitled: “The Coming Revolution”):

“Army modernization efforts must begin at the top with a command focus on grand innovation through leadership, encouragement, and communication. Such programs, however, can be more powerful if they reach down to the lowest level of the organization to solicit crowdsourced input for broad organizational changes. In fact, this kind of innovation, long a part of the Army’s lifeblood, is critical to profitability sustainment in the corporate world. In uplifting, supporting, and funding Soldier-led concepts, military commands may harness the true power of the idea.”

In this regard, let us ask our soldiers — at “the lowest level of the organization” — to help our leadership overcome a critical problem; one which is adversely effecting both the nation, and the “force” (and, thus, our national security), today.

This such problem being, how to “fight back” against an opponent/a competitor who has learned how to use the more-conservative/the more-traditional elements of one’s own and other populations; this, so as to effectively “contain” — and so as to effectively “roll back” and possibly destroy — the power, influence and control of the U.S./the West.

Explanation:

In the Old Cold War of yesterday, the U.S./the West learned that it could, using the more-conservative/the more-traditional elements of the world’s populations (to include those such elements in the communists states themselves) “contain” — and ultimately “roll back” and destroy — the power, influence and control of the Soviets/the communists.

In this regard consider, for example, the role that such things as “religion” — and specifically the role that Pope John Paul II had — in ending the Old Cold War:

“Without the Pope, no Solidarity. Without Solidarity, no Gorbachev. Without Gorbachev, no fall of Communism. (In fact, Gorbachev himself gave the Kremlin’s long-term enemy this due, ‘It would have been impossible without the Pope.’ ” (See the Public Broadcasting System [PBS] “Frontline” article “John Paul II and the Fall of Communism” by Jane Barnes and Hellen Whitney.)

Today our opponents/our competitors, such as Russia, have decided to use these exact same strategies, methods and tactics now against the U.S./the West — for example — as described below:

“In his annual appeal to the Federal Assembly in December 2013, Putin formulated this ‘independent path’ ideology by contrasting Russia’s ‘traditional values’ with the liberal values of the West. He said: ‘We know that there are more and more people in the world who support our position on defending traditional values that have made up the spiritual and moral foundation of civilization in every nation for thousands of years: the values of traditional families, real human life, including religious life, not just material existence but also spirituality, the values of humanism and global diversity.’ He proclaimed that Russia would defend and advance these traditional values in order to ‘prevent movement backward and downward, into chaotic darkness and a return to a primitive state.’ ” (See the Wilson Center publication “Kennan Cable No. 53” and, therein, the article “Russia’s Traditional Values and Domestic Violence,” by Olimpiada Usanova, dated 1 June 2020.)

Bottom Line Question for Our Young Soldiers:

How might you help your leadership overcome the — exceptionally critical it would seem — problem that I have identified above? What advice would you given them in this regard?