As global politics and the international order destabilize, planners, strategists, and warfighters the world over are reminded that the threat of armed, large-scale conflict is a central feature in the histories of states. Recent conflict between China and India in the Galwan Valley and ongoing military buildups in that region testify to this fact. While the destruction of property and loss of life inherent in large-scale conflict presents occasion for lament, and ought to be avoided at all costs, nevertheless the historical reality of war, and of human nature itself, compels students of war to think carefully about the character of future armed conflict. As planners and strategists imagine future wars—and in particular, the next large-scale, peer-competition conflict—they would do well to think on the means by which such wars will be won or lost, where they will be won or lost, and how victors will deploy military power to achieve overmatch.

To that end, the editors at WAR ROOM have invited practitioners and scholars across the landscape of professional military education and academe to consider the following question:

“In the next large-scale, peer-competition conflict, what will be the critical (or decisive) domain of warfighting, and why?”

Their illuminating responses, posted below, speak to the enduring character of war and to the imagined future of large-scale, peer-competition conflict.

Dr. Mitchell G. Klingenberg, Department of Military Strategy, Planning, and Operations, U.S. Army War College, assembled and edited this Whiteboard symposium.

Readers are invited to make their own contributions in the comments section.

1. Lieutenant General (Retired) Bob Caslen, President, University of South Carolina

Clausewitz’s ‘Paradoxical Trinity’ reminds us that war is a political act where conflict occurs across an alignment of three fundamental elements: the objectives of the state, which the theorist contends operate in rational thought and reason; the emotions or passions of the people, which can inflame or calm depending on external factors; and the skill of the military, which can either mitigate the inherent friction and fog of war or fall victim to it. Clausewitz asserts that these elements define the immutable nature of war.

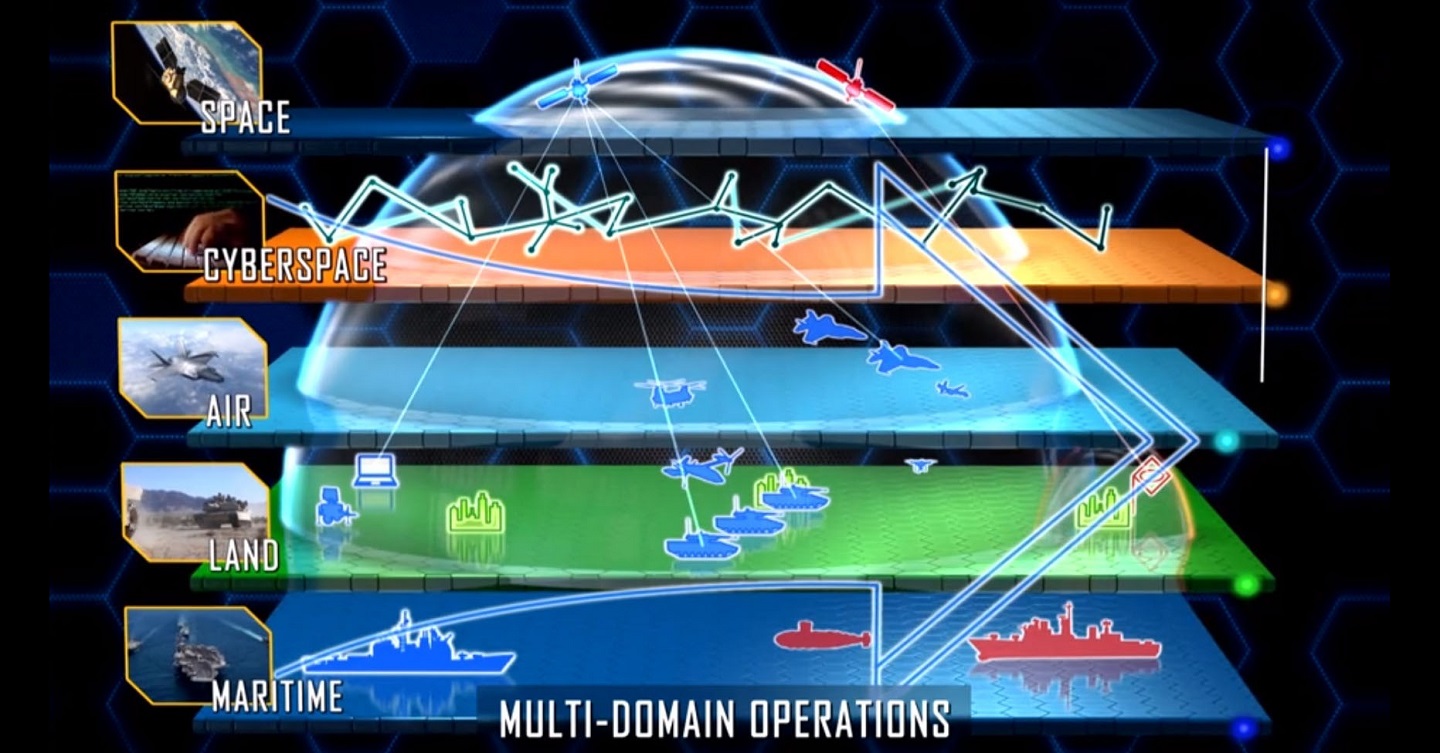

The character of war, however, evolves across domains in which it occurs. For more than 100 years those domains have included land, maritime, and air. More recently, however, space and cyber have been recognized as emergent domains that have fundamentally changed the character of conflict. Today’s American doctrine of multi-domain operations recognizes that synchronized actions across each of these domains are needed to achieve victory against peer competitors.

Technological or organizational change, exceeding the rate of change by an opponent, in any domain, will impact the probability of victory in conflict. However, the likelihood of a competitor ‘leaping ahead’ (or falling precipitously behind) is most probable in one of the ‘newer’ domains. This implies that, at least for the relative near term, space and cyber may be critical, possibly even decisive, to future combat success.

While space is a newly defined domain, activities in space remain bound by the laws of physics, so actions in that domain resemble the more traditional domains of land, sea, and air. Operations in the cyber domain, however, allow combatants to direct pressure on the basic connective tissue that Clausewitz saw in his Paradoxical Trinity: reason, emotion, and friction. The potential to place or reduce stress on these elements through cyber activity makes the cyber domain, at least for now, the most critical and even decisive domain.

Synchronous actions across all domains are needed to assure success in war. But given the greater-than-proportional impact on operations the United States military can now achieve in the cyber domain, institutions like the University of South Carolina become more essential to the national security. Universities educate leaders, stimulate thinkers, and train technical experts to leverage the cyber domain to achieve the political outcomes that Clausewitz reminds us are the reason mankind goes to war.

2. G.K. Cunningham, Ph.D., Professor of Strategic Landpower, Department of Military Strategy, Planning, and Operations, U. S. Army War College

Domains are all the rage these days. At one time, our Neolithic ancestors conceived of the universe merely in terms of its observable features: air, water, land, and the heavens above. This mode of thought has proven adequate for millenniums. But in these postmodern days, proponents and factionalists each claim sovereignty over a seemingly ever-increasing array of domains: the air domain, the sea domain, the land domain, the space domain, and the cyber domain. There is talk of adding a human domain, although what that might actually mean has not been clearly articulated. Maybe the information domain could also make the list.

The fundamental truth remains that in large-scale, peer-level competition and conflict in the 21st century, landpower will endure as the critical domain of warfighting. People inhabit the land. They may sail over the seas, fly through the air, and occasionally pop into space. However, for all the utility and the essentiality of domains of information, ideas, and the electro-magnetic spectrum, no one lives in any of those domains. People live on the land. Commerce takes place on land (and merely across seas). Ideas are generated and taught to succeeding generations of eager youth there, and societies are acculturated on the land. As T. R. Fehrenbach pointed out decades ago in his classic history of the Korean War, land is the persistent place where human beings become civilized and preserve the fullness of their humanity:

You may fly over a land forever; you may bomb it, atomize it, pulverize it, and wipe it clean of life—but if you desire to defend it, protect it, and keep it for civilization, you must do this on the ground, the way the Roman legions did, by putting your young men into the mud.

Nothing in the 21st century has changed any of that. For all their advances in science, technology, and engineering, humankind still confronts the same problems they always have faced using the same intellects and psychology they have possessed since Cro-Magnon times—on land. Hence, the land domain will again prove to be the dominant, decisive one.

3. Wayne Wei-siang Hsieh, Ph.D., Professor of History, History Department, U.S. Naval Academy

As a historian, part of me remains leery of exercises such as this, but they obviously serve a purpose as a means to provoke discussion—assuming all the usual caveats are given about the importance of complexity and context.

Using the current doctrinal definition of domains—cyber, space, air, ground, and sea—I would declare ground to be the critical domain. This is not to gainsay the importance of other domains, but to highlight the importance of where human beings still spend most of their daily lives, working, living, fighting, and dying.

Because the other domains impinge upon the terra firma and sometimes require esoteric technologies and platforms, a judicious allocation of resources might actually prioritize other domains, especially in a theater of operations such as the Western Pacific. However, while the challenges of Anti Access/Area Denial (A2/AD) in such a theater might be in large part technological, and might require proportionate commitments in human and financial resources, we should not forgot the whole rationale behind preserving access to any specific geographical region. Whether it be preserving freedom of navigation in the South China Sea, or defending American interests in Taiwan, preserving access via the sea, air, and cyber domains all remains keyed to access to the dry land on which human beings live their lives.

Furthermore, in a conflict among peers, the importance of Max Weber’s analysis of the state as “a human community that (successfully) claims the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory,” hardly requires repeating. In the final analysis, only military forces on the ground can establish such a monopoly, and as a fundamentally status quo power, in most projected peer conflicts, the United States will be aiming to preserve its allies’ ability to maintain such a monopoly on their own sovereign territory.

4. Paul Povlock, Ph.D., Associate Professor, Joint Military Operations Department, U.S. Naval War College

During the Cold War, when describing the rationale for the expanding number of Soviet Airmobile Brigades populating the Warsaw Pact Table of Organization and Equipment, there was an adage attributed to the Soviet Army that “the Rotor is to the track as the track is to the boot.” The impressive array of Soviet airmobile forces would allow the Warsaw Pact to achieve an overpowering advantage over the defending NATO forces along the West German border. In theory, this advantage derived not so much from Soviet technological superiority in airframes, or from numbers of fearless airborne troops, but from the Soviet ability to significantly increase the operational tempo of their invading armies beyond what defenders could react to or comprehend. By delivering a synchronized, operational-level blow well into the entire depth of Western defenses, the Soviets might hope to force a catastrophic early culmination of NATO’s military forces on the central front in Europe.

Today, the possibilities for an offensive in the cyber domain, well synchronized with other conventional and space forces, may have the greatest opportunity for decisive effect in any large-scale, peer-competition conflict. This is not because the impressive speed of cyber weapons makes the earlier speed comparison anachronistic (perhaps “Cyber is to the telephone as the telephone is to the homing pigeon” is a better adage for today), or even because of any long term effects these ethereal attacks may leave on any command and control system. Certainly, the speed of conventional units has not increased greatly (if at all) since the end of the Cold War, though the accuracy, range and lethality of hypersonic missiles do give one pause. Instead, the ability to significantly degrade, denude, and deceive the opposing commander’s operational-level view of battle may prevent him or her from making relevant decisions at decisive moments before being overwhelmed—physically or cognitively—by synchronized enemy forces operating in multiple domains. Such a well-constructed offensive need not be quantitatively or qualitatively superior to the enemy to achieve one’s objective, but it must be organized to take the maximum potential of the possibilities of this emerging domain in concert with other forces.

During the invasion of France in 1940, the speed, depth, and audacity of German attacks across multiple domains overwhelmed the ability of Général d’armée Maurice Gamelin, the French commander, to influence events at the front. Even if the French command had had an effective telephone network, it is doubtful their communications could have increased resistance to the well-synchronized German blow. In the next large-scale, peer-competition conflict, commanders may possess only minimal communications with subordinate forces, and half of the information they receive may have been deliberately distorted to further obstruct their decision-making capacity. Perhaps we should keep the homing pigeon barns in operation.

5. Ethan S. Rafuse, Ph.D., Professor of Military History, Department of Military History, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College

“It’s tough to make predictions,” Yogi Berra is reputed to have observed, “especially about the future.” This is certainly the case with armed conflict, the realm of Clausewitzian fog, friction, chance, and uncertainty. There can be little doubt that the effects of new communication technology, logistical factors, and advances in weaponry on future warfare will be significant and the degree to which militaries adapt effectively to change in these areas will go far in determining what happens on the battlefields of the future. Yet, as important as tactical and operational effectiveness is, it is ultimately, Allan Millett and Williamson Murray concluded from their study of the great wars of the first half of the twentieth century, “more important to make correct decisions at the political and strategic level than it is at the operational and tactical level. Mistakes in tactics can be corrected, but political and strategic mistakes last forever.”

Few things play a greater role in shaping the ability of leaders to effectively shape the strategic context in which armed conflicts take place than civil-military relations, which play out in three realms: the interactions between civilian political authorities and leaders of the uniformed military, the relationship between the military and the society it serves, and the relationships between the military and civilian populations in areas of major operations. Recent conflicts have provided vivid illustrations of how all three shape the ability of leaders to establish a healthy relationship between ends, ways, and means—and play a critical role in determining the course, conduct, and outcome of wars. There is no reason to believe the next large-scale, peer-competition conflict will be any different.

6. Heather P. Venable, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Military and Security Studies, Department of Airpower, U.S. Air Command and Staff College

Regarding the prospect of a large-scale, peer-competition conflict—especially with China—one often hears that future conflict would be conducted largely in the domain of maritime operations. After all, the oft-quoted (though rarely heeded) advice to “never fight a land war in Asia” looms large. It is problematic, though, to accept this claim as axiomatic, especially since an enemy’s key center of gravity might be located on the land, and forces operating in many domains might be capable of striking land targets.

But whatever the case may be, there is no single decisive domain, since decisiveness occurs only when the civil or military leadership of one’s adversary decides to change their behavior. Thus, hoping for an outsized advantage in one domain of military operations to achieve decisiveness in future conflict would be problematic.

Two key points require the utmost consideration. First, one must determine what the enemy most values to affect the greatest target of all: the enemy’s will. One may focus on destroying an enemy’s means to affect its will, or one may seek to attack the will itself. And, of course, one may strategize to attack both the means and will of an adversary simultaneously. Regardless, only by degrading or diminishing an enemy’s will can civil and military planners hope for an enduring peace. This key causal mechanism has largely been absent from discussions of proposed operational solutions such as air-sea battle and multi-domain operations.

What really matter are the effects, generated in one or multiple domains, that can change an opponent’s behavior by imposing an unacceptably high cost on continued military action. Still, as Robert Pape reminds us, effective coercion can prove extremely costly, a reality that politicians often fail to appreciate in their (understandable) desire to do something in response to crises.

Photo Description: Multi-Domain Operations as seen by the Army, as part of the joint force, can counter and defeat a near-peer adversary capable of contesting the U.S. in all domains, in both competition and armed conflict.

Photo Credit: U.S. Army Training Support Center

Other releases in the “Whiteboard” series:

- THE ADMINISTRATION’S TOP FOREIGN POLICY PRIORITY (A WHITEBOARD)

- AFTER 2020, WHAT’S NEXT? (A WHITEBOARD)

- THAT ONE MOST IMPORTANT THING: (A WHITEBOARD)

- SHALL WE PLAY A GAME?

(WARGAMING ROOM) - WAR(GAMING) WHAT IS IT GOOD FOR? (A WHITEBOARD)

- LEADERSHIP ROLE MODELS IN FICTION REVISITED: (A WHITEBOARD)

- WHAT GOOD IS GRAND STRATEGY? (A WHITEBOARD)

- THE UNITED NATIONS’ GREATEST ACCOMPLISHMENT: (A WHITEBOARD)

- LEADERSHIP ROLE MODELS IN FICTION: (A WHITEBOARD)

- THE MOST IMPORTANT LEGACY OF THE VIETNAM CONFLICT: (A WHITEBOARD)