The problem, due in large part to Clausewitz’s meandering style, is that too many influential commentators have treated those books as how-to manuals.

Carl von Clausewitz’s text, On War, ascends to the status of sacred text in many circles. Military leaders and politicians quote him, and it is rare to find a professional military education syllabus without excerpts of the book. But the reality is that the 19th century Prussian text is also difficult, and most people, even military strategists, do not have the time or inclination to read it. But they should. Clausewitz can be useful and accessible —but getting to the usable parts means getting past the sections that were never meant to be used in the first place.

What War Is Is Different Than How You Fight a War

This distinction is a real problem with real ramifications. A lot of readers over the years have misunderstood what Clausewitz was doing with Books One and Two. Book One is “On the Nature of War,” and Book Two is “On the Theory of War.” That is literally all they are. Book One is meant to explain what war is—to define its fundamental characteristics and to distinguish it from other human interactions, especially in peacetime. Book Two is Clausewitz’s idea of what theory is—a guide to study of a complex phenomenon—and is not—a list of rules to follow—when it comes to war.

The problem, due in large part to Clausewitz’s meandering style, is that too many influential commentators have treated those books as how-to manuals. But neither book is meant to tell readers how to fight and win wars. They are not prescriptive, and they should not be read that way.

For example, when Clausewitz writes about “the maximum use of force” in war (p. 75) or that “there is only one means in war: combat” (p. 96) or that “essentially war is fighting” (p. 127), he was not calling for the overwhelming use of force—decisive battles—as the preferred way to wage wars. What he was saying was that if war took place in a pristine lab, it would go to a limitless extreme. For example, imagine two polities, A and B, get into a violent confrontation in that lab.

A slaps B, so B punches A. A kicks B, B hits A with a club, so A hits B with an axe. B shoots A with a pistol, so A shoots B with a machine gun, and B responds by firing a bazooka at A. A brings in the artillery and shells B, and B drops a 1,000 lbs. bomb on A. A shoots a tactical nuke at B, and B uses a thermonuclear device on A, and so on, back and forth, until they reach some sort of hypothetical extreme. In a purely logical sense, war should go up this tit-for-tat scale to its most extreme form, since both A and B know that war will get there eventually, they will jump to the most extreme measures right away.

It was a thought experiment to understand the full dimensions of what war could be. But Clausewitz, having explored the extreme, injects a dose of reality. In the real world, wars rarely move to the extreme where both sides were doing everything to win.

Clausewitz then sets out to explain why war does not go to its theoretical absolute extreme form. His answer, in part, was that war was neither pure escalatory violence nor purely political. Rather, the nature of war is that it is best understood as the interplay among a trinity of forces: passion, chance, and reason.

Say that A and B are now out of the lab. A dumps chemicals into a river that flows into B’s territory and kills thousands of B’s children. B decides to use violent force against A. A resists, and war breaks out. B is passionate about killing everyone in A. When B makes the calculation about the probability that it can kill all of the enemy, it determines that it can be done. The war seems headed to its extreme. But then B reflects on the purpose of the war and realizes that what it really wants is that A cannot dump chemicals upriver again. One way is to kill all of A, but B could also just take control of the land upriver, so that A no longer has access. Besides, in the course of the fighting B figures it has killed enough of A’s people that justice has been served. Also, killing all of A’s people has become unpopular with some people at home, and C and D have come along to tell B that they are worried about B killing all of A. So B backs off, and the war never goes to its hypothetical extreme.

In this case, the passion was there, and B figured that chance favored taking war to its extreme, but reason tempered its enthusiasm. Forces interact and moderate each other. And every war is different. The pull of reason, passion, and chance change over the course of war, and variation is endless. That is what makes war more than a chameleon, because it not only changes for each case, but it changes within each case, as the situation develops. The point is that in Book One, Clausewitz was only trying to get a handle on the nature of war. He was not directing military strategists to figure out how to fight the biggest, most decisive and violent battle. Nor did he think that strategists should try to win by seeking out some proper balance in the trinity. Military strategists get stuck when they try to apply these ideas to the practice of war because they were not meant for application.

Attempts to develop rigid principles for strategy always find exceptions, which was what Clausewitz criticized in his predecessor theorists…

Don’t Throw Away On War Just Yet

But there is more to On War than the first two books. For military strategists, who should be primarily interested in how to fight and win wars, Book Three is one place to go.

If we have an agreed upon definition for making military strategy, it is closest to B.H. Liddell Hart’s: “the art of distributing and applying military means to fulfill the ends of policy.” (p. 335) The Army War College boiled this down to a simple model of ‘the alignment of ends, ways, and means, balanced by risk.’ That model has had staying power because it is broadly true. Every proposed path for winning a war or in a theater of war must have interrelated objectives, approaches, and resources that are available and applicable to the specific problem at hand.

However, that model is so broadly true that it is not all that helpful in actually making strategy. In fact, it is so broad that it can be applied to almost any military effort, down to tactical engagements. For example, our platoon (means), is going to flank and destroy the enemy strongpoint (ways), in order to seize the town (ends). As such, there is nothing in that definition that is particularly useful for the dilemmas of making war at the national or theater level. It simply scales up a tactical truism to a larger scope. Our Joint Task Force (means) is going to attack the enemy homeland (ways) in order to threaten their capital and force them to sue for peace on our policy terms (ends).

That all sounds fine and good, but it is also exactly what Clausewitz was critiquing as insufficient in military strategy. This is where he says, “Everything in strategy is very simple, but that does not mean that everything is very easy.” (p. 178) His point is that wars and theaters of war are on scales of complexity much greater than campaigns and engagements. We understand this, which is why our militaries constantly develop clear doctrinal methods for all manner of tactical actions but not for strategy. The variations and complexities of wars and theaters of war make stepwise techniques foolhardy.

Attempts to develop rigid principles for strategy always find exceptions, which was what Clausewitz criticized in his predecessor theorists such as Henry Lloyd, Dietrich von Bülow, and the early work of Antoine Henri Jomini. That is not to say there are no “physical, mathematical, geographical, and statistical” strategic elements that usually hold true (p. 183). Indeed, Clausewitz identifies the importance to good strategy of considering superiority of numbers, surprise, concentration of forces in space, unification of forces in time, strategic reserves, economy of force, pauses, lines and angles, and so on.

However, and this is what is most important from Clausewitz, he puts all of those elements after and in the context of “Moral Factors,” which he considers far more important to military strategy. By “moral,” Clausewitz was not talking about ethics or issues of right and wrong—“morale” would be closer in our contemporary lexicon—and he identifies “the skill of the commander, the experience and courage of the troops, and their patriotic spirit,” as the principal factors for military strategists to consider. Over the rest of Book Three, Clausewitz wanders around these factors, relating commander and troop boldness, perseverance, superiority of numbers, surprise, and cunning to physical, numerical, temporal, and geometric considerations. None of these moral factors can be quantified or otherwise made into rigid laws, making them difficult to capture into any sort of strategic theory.

And so we have not. In fact, we hardly deal with them at all in strategic doctrine or education. When was the last time any military strategic planning formally included considerations of these moral factors: the skills of the commanders involved and their particular levels of boldness, cunning, and perseverance? How often when making military strategy do we explicitly factor in the varying levels of skill, courage and patriotic spirit of the troops?

Of course, there is no denying that Clausewitz is right—history is littered with examples showing that the best strategy on paper failed in execution because the commander was not bold enough, or that patriotic and enthusiastic raw troops were wasted in an effort trying to do some mission that only highly skilled professionals could pull off.

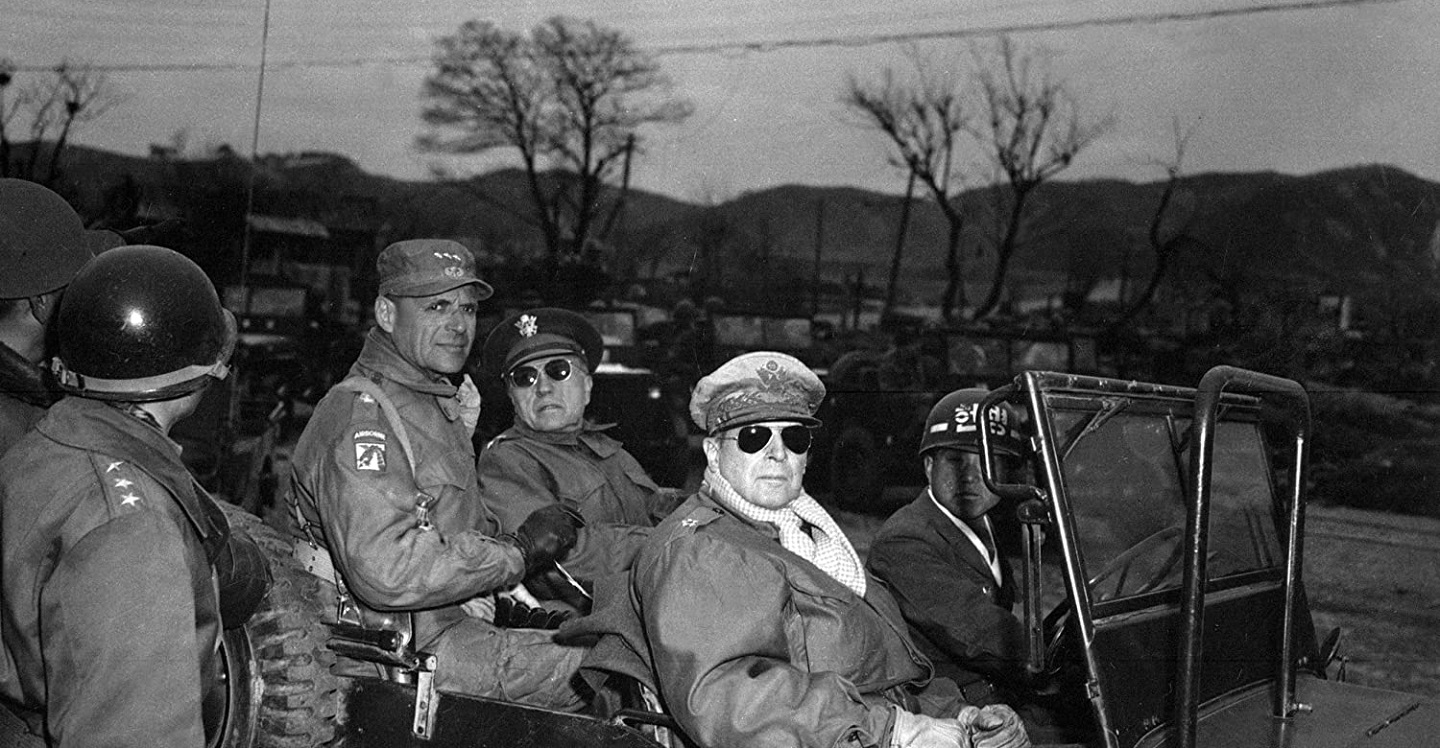

Far too often as strategists define objectives and create lines of effort and all the rest, these moral factors are left unstated. At worst they are not considered at all, and we just hope that every commander has the requisite (and identical) skill set and that every formation of troops is roughly the same when it comes to these military virtues. At best we hope that the moral factors are calculated inside the heads of individuals or teams in command. These informal considerations can be pretty good. For example, Matthew Ridgway’s particular style of gritty inspirational leadership was exactly what the less-than-enthusiastic troops needed in Korea, especially after they dealt with the more distant Douglas MacArthur.

Such examples only strengthen Clausewitz’s case. If the moral factors end up being at least as important as the conceptual or physical ones, we should make them a more formal part of our studying, teaching, and practicing of military strategy. On War is a fine place to start, but put down Books One and Two for a while. Take a closer look at Book Three instead.

Thomas Bruscino is an Associate Professor in the Department of Military, Strategy, Planning and Operations at the U.S. Army War College and the Editor of the DUSTY SHELVES series.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

Photo Description: Lieutenant General Matthew Ridgway; Major General Doyle Hickey; and General Douglas MacArthur, Commander in Chief of United Nations Forces in Korea, in a jeep at a command post, Yang Yang, Korea, approximately 15 miles north of the 38th parallel, April 3, 1951.

Photo Credit: U.S. Army photo, Grigg