Design is wonderfully adaptive to ambiguity.

The Army has extensive experience with crafting theater strategy, but there is a need to be more deliberate in its institutional strategies. In this candid interview, Mr. Robin Swan discusses the Army’s shortcomings in preparing strategists to grapple with crafting institutional strategy, specifically the failure to apply design thinking and operational design methodology. Mr. Swan is the Director of the Office of Business Transformation (OBT) in the Office of the Under Secretary, Headquarters, Department of the Army (HQDA), an office he joined over eight years ago. He has been described as “totally unafraid to take prisoners,” a reputation that has clearly yielded results, as he was instrumental in answering the call of senior leaders to reform the Army to pay for higher priorities like modernization. This he accomplished by realigning $32 billion over Program Objective Memorandum (POM) 20-24 alone. A retired general officer, Mr. Swan served as the Army’s senior strategist in the position of Director, Strategy, Plans, and Policy (DAMO-SS), G-3/5/7, HQDA. He also shaped how the Army views operational art as the Director of the School of Advanced Military Studies.

THOMAS: When I arrived at OBT, the problems we were grappling with seemed very different than what I had experienced before or for which I was educated to handle at Fort Leavenworth. How well do we prepare officers to develop institutional strategy?

SWAN: I recall my frustration when I became the DAMO-SS, after spending two years in Iraq. I was familiar with crafting theater strategy and the linkage of that theater strategy to the National Defense Strategy and the National Security Strategy within the purview of the CENTCOM commander. We have focused doctrinal development on the evolution of operational art, which has caused us to think of strategy—in particular at the Army War College—as the nexus between theater strategy and tactics. The natural tendency has been to think of strategy primarily within the context of campaigns and major operations. We developed not just curricula, but an entire school, the School of Advanced Military Studies, to focus on creating operational artists who can translate theater strategic direction to outcomes through the design of campaigns and major operations. And then we developed the functional area 59 [Army Strategist career field] primarily focused on working at Combatant Commands and Army Service Component Commands with an operational bent toward theater strategy.

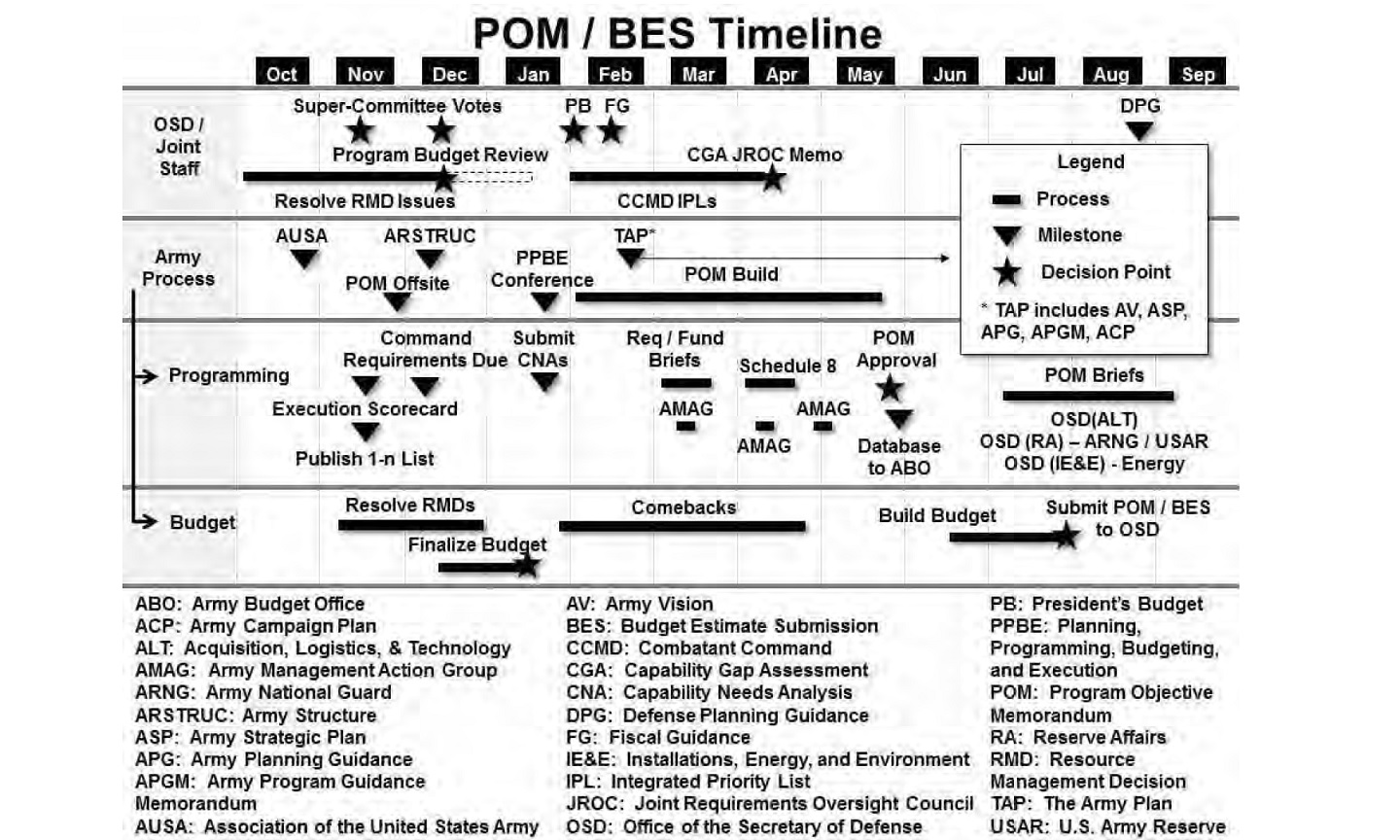

We are very comfortable making adjustments [to framing] within a theater of operations. On the institutional side, we’re not so comfortable with it. Why? Because we have this very mechanistic process called the PPBE [Planning, Programming, Budgeting, and Execution] cycle. We have to prepare our POM [a service’s recommendation for funding over the next five years] input and submit it to the Office of the Secretary of Defense for inclusion in the creation of the next president’s budget. The Army goes through repetitive programming cycles associated with a strategy, changing the fiscal frame a number of times within any given year. Whenever we receive or have money taken away from something, the ends have to change. And we need the institutional acuity to continue to change.

THOMAS: Can you elaborate more on what you mean by a frame changing? Also, if ends change, am I correct in assuming you are implying that the “ends, ways, and means” approach to strategy is insufficient?

SWAN: Regardless of what frame you want to overlay on the institutional Army today, we live within the DoD universe that has a couple of frames relative to a design methodology. We have an environmental frame, a political frame, an economic frame, an informational frame, a data driven frame, an external factors frame, and a combatant commander’s viewpoint of what kind of capabilities we need in the future to be able to provide the joint force. Those frames exist today. So how are we iteratively getting after those frames because any action within that frame changes the system within which it is viewed?

It’s like Newton’s first law: every object in a state of uniform motion will remain in that state of motion unless an external force acts on it. You put a force in a system, an activity occurs within that system, it ripples within that system so you can say there’s an end relative to a particular frame but if there is activity that upsets that balance within that frame, the end has to change. Those consistent and constant changes mean that the concept of ends does not really get us there. We see the ground shift underneath us all the time. So saying there is this dogmatic “end” is problematic and, frankly, it’s counter to design thinking because design thinking is meant to consistently challenge the frame that you’re in and reframe as required and gain strategic flexibility for overcoming those capabilities.

THOMAS: What’s a better alternative then to “ends, ways, and means”?

SWAN: In the civilian education system, if you take a look at who teaches strategy, it’s primarily business schools. The best definition of strategy that I’ve read came from the Harvard Business Review: it’s fitting ourselves into the environment to the betterment of senior leader strategic direction. That has a link within theater strategy for the achievement of national objectives within a theater of operations and translates to operational art, certainly. How does that apply to institutional strategy? How do we ensure that we have the right joint force, at the right readiness state, with the right capabilities to meet the objectives of the National Defense Strategy?

Our current strategic direction is to increase our readiness, increase our modernization, and pay for it through reform activity in order to free up time, money, and manpower for reinvestment in higher priorities. That is an articulation of an institutional strategy. But then how do we take that strategic direction and translate it to actual action within the institutional Army? That is a separate art form that, quite frankly, strategists have not spent a lot of time on from a developmental standpoint. We have struggled to apply the same type of disciplined thought processes that we do in theater strategy.

THOMAS: What tools should a strategist hone to navigate the challenges of both?

SWAN: They both require a set of tools to be able to develop innovative, workable strategies. I’m suggesting that the design approach is the best for that from a framing perspective to generate options.

Strategists must have the mental flexibility of design thinking to frame and consistently reframe, and then present results to decision-makers. If we do that, we have a dynamic, living Army strategy—and that strategy is an institutional strategy. It guides each one of our Army Commands, it guides our Army Service Component Commands and how they interact with their Combatant Commands. It guides the Army Staff and the Secretariat. We have to be comfortable dealing at that level. Remember, design is wonderfully adaptive to ambiguity.

Do we have the right skill set as individuals to be able to really get after the type of design thinking that is going to be required to stay on a path of increasing readiness and modernization going forward? That is a fundamental question that strategists should be interested in.

THOMAS: Can you give a specific example in which applying design thinking could benefit institutional strategy to make this more concrete for the reader?

SWAN: As a Functional Area 59 [strategist] officer sitting inside the Pentagon, what are the techniques to adequately frame a strategy upon which campaigns and major operations—in a metaphysical sense—can be translated to drive the Army so that we have the resources for our future needs? I’m not saying it hasn’t been done, but I have yet to see a group convened that says let’s do the institutional strategy framing relative to POM 22-26 [Army spending recommendations for fiscal years 2022-2026], for example.

The recent Residential Communities Initiative wasn’t an issue of national strategy nor of theater strategy, it was one of institutional strategy. It was a late input into the army programming system and it drove a programming change. We didn’t start off building POM 21-25 thinking we were going to put eight to nine hundred million into facilities in those years. The environment changed. The ends changed. So how are we thinking about the kind of strategic battle drills we need inside the institutional Army to make those adjustments?

THOMAS: What assignments are going to best prepare me to be a successful strategist, particularly concerning the difficulties associated with institutional strategy?

SWAN: I think it was, and perhaps still is, a badge of honor for how long officers could avoid assignments to the Pentagon. It’s shocking to me. Take a look at people who seem able to navigate the waters better than others, particularly from an institutional strategy perspective. They have had repetitive assignments here and in tough positions.

It takes mental flexibility to apply a design approach when dealing with and operating in these positions. You have the Office of the Secretary of Defense, the administration, and Congress. Because the Army is multi-component, you have state and territorial governors with Title 32 [authorities for state employment of the National Guard]. All entail particular institutional frames that you aren’t dealing with in the same manner with theater strategy.

Inside the building and supporting the Chief of Staff in his Title 10 [service chief] role and also as a member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, you have to have a very adaptive strategist who can live equally in both worlds: the grand theater strategic world and that of the institution. It’s all a mental exercise. One day handling approaches to North Korea, the other thinking about what functions can the Army absorb from the Defense Logistics Agency to free up additional resources.

THOMAS: Sir, thanks for sharing your thoughts. I’ve learned a lot about the mindset necessary for institutional strategy.

SWAN: [Smiles] Then again, I could be wrong.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Major Petra Thomas is a Strategist in the Office of Business Transformation, Headquarters, Department of the Army. Mr. Robin Swan is the Director of the Office of Business Transformation, in the Office of the Under Secretary, Headquarters, Department of the Army. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and the interviewee and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

Photo Description: Program Objective Memorandum / Budget Estimate Submission Timeline

Photo Credit: How The Army Runs: A Senior Leader Handbook 2017-2018 (31st Edition) Figure 8-12, pg 8-38

There are three strategy applications:

1. Force Employment Strategy Application: Typically taught by War Colleges to students. This application typically has the life of an Theater Operational Plan – at most -2 to 4 years.

2. Force Administration Strategy Application: Generally not taught. This strategy contains (a) personnel policy and accession policy, (b) training policy and facilities (c)basing, presence and rotational deployment policy including coalition cooperation opportunities (d)equipment acquisition, modernization, and retirement cycles. This application typically cannot be fully implemented in less than 20 years across a service.

3. Force Design and Force Planning Strategy Application: Typically not taught. This strategy application is best described as a ” A Campaign Across Time to Create and Sustain Force Capability and Capacity” often conducted in the absence of a consistent “Commander’s Intent”. A Force Design and Force Plan typically takes about 25 years to fully implement. Remember that a piece of major equipment takes about 15 years from conception to IOC and then has a 20 year production life. Each item then has a 25 to 40 years – Think M-1 Tank and F-35.

Force Structures outlive the Geo-Politico Epoch’s that can them into existence. The Competitive Global Power Epoch was predicted in framing AOA’s in 1995 as arriving in 2015. The participants and their respective GDP were also predicted accurately. The implication is that a mature sustained force architecture and strategic planning organization is essential to provide necessary course correction. Such an organization serves as navigators and the Force Design and Force Planning Strategy Application is best thought of as navigation toward a Policy defined destination.

War Colleges should teach that there is a fundamental distinction between thinking strategically and acting strategically. Most war college graduates can think strategically but when faced with a Force Employment Crisis, to act strategically means (1) Define the problem in terms of the theater operational objectives, (2) Marshall resources from organic or supporting organizations to cope with the crisis in a timely, operationally effective, and economic manner, (3) disengage the needed resources from their current employment, (4) apply the resources to the problem, and (5) disengage the resources and return them to support the revised plan.

Please note: an uncorrected error in the Force Administration Strategy application 15 years before the Force Employment Crisis may well prevent the operators from acting strategically because skills needed this week are simply not available in the force and it takes three years to create them and retrain the force. A major uncorrected mistake in the Force Design and Force Planning Strategy Application 25 years before the crisis may mean that the physical tools are absent.

This note advocates for a Full Spectrum Army capable of functioning in real time across the spectrum of conflict. Remember that Conventional Warfare is a short episode surrounded continually by unconventional warfare.

One further thought:

If Force Design and Force Planning is a Campaign across Time to Create and Sustain Force Capability and Capacity with a 25 year duration – analogous to navigation to a policy destination then the POM is simply an exercise to avoid the “Hazards to Navigation”.

Remember there is a five year POM but it is revised every year. The article focuses on POM management without a reference to the strategic planning background. The fact is that no force administration strategy will be implemented within a single POM.