- (PART%203)\%22>(PART%203)\%22>(PART%203)\%22>The%20final%20installment%20in%20our%203%20pt%20series.%20The%20team%20discusses%20how%20a%20historical%20mindset%20can%20help%20individuals%20sort%20out%20what%20information%20is%20valid%20or%20not%20%40notabattlechick&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwarroom2.armywarcollege.edu%2Fpodcasts%2Flessons-of-history-3%2F&hashtags=War_Room #WPNS #historicalmindedness" title="Share on Twitter" onclick="essb.window('https://x.com/intent/post?text=(PART%203)\%22>(PART%203)\%22>(PART%203)\%22>(PART%203)\%22>The%20final%20installment%20in%20our%203%20pt%20series.%20The%20team%20discusses%20how%20a%20historical%20mindset%20can%20help%20individuals%20sort%20out%20what%20information%20is%20valid%20or%20not%20%40notabattlechick&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwarroom2.armywarcollege.edu%2Fpodcasts%2Flessons-of-history-3%2F&hashtags=War_Room #WPNS #historicalmindedness','twitter','1213829686'); return false;" target="_blank" rel="noreferrer noopener nofollow" class="nolightbox essb-s-bg-twitter essb-s-bgh-twitter essb-s-c-light essb-s-hover-effect essb-s-bg-network essb-s-bgh-network" >

You cannot help but approach your sources from your own experiences and backgrounds

Our three-part roundtable on the “Lessons” of History concludes as Con Crane, Jacqueline E. Whitt, and Andrew A. Hill discuss the importance of critical thinking for developing historical mindedness. From the subjectivity of first-person accounts to the modern phenomenon of so-called “fake news,” what is presented as definitive history is almost assuredly not. How can a historical mindset help individuals sort out what information is valid or not? How can we construct useful and clear understandings of what happened in the past?

Podcast: Download

Con Crane is a military historian with the Army Heritage and Education Center. Jacqueline E. Whitt is Professor of Strategy at the U.S. Army War College. Andrew A. Hill is Chair of Strategic Leadership at the U.S. Army War College. The views expressed in this presentation are those of the speakers and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, U.S. Army, or Department of Defense.

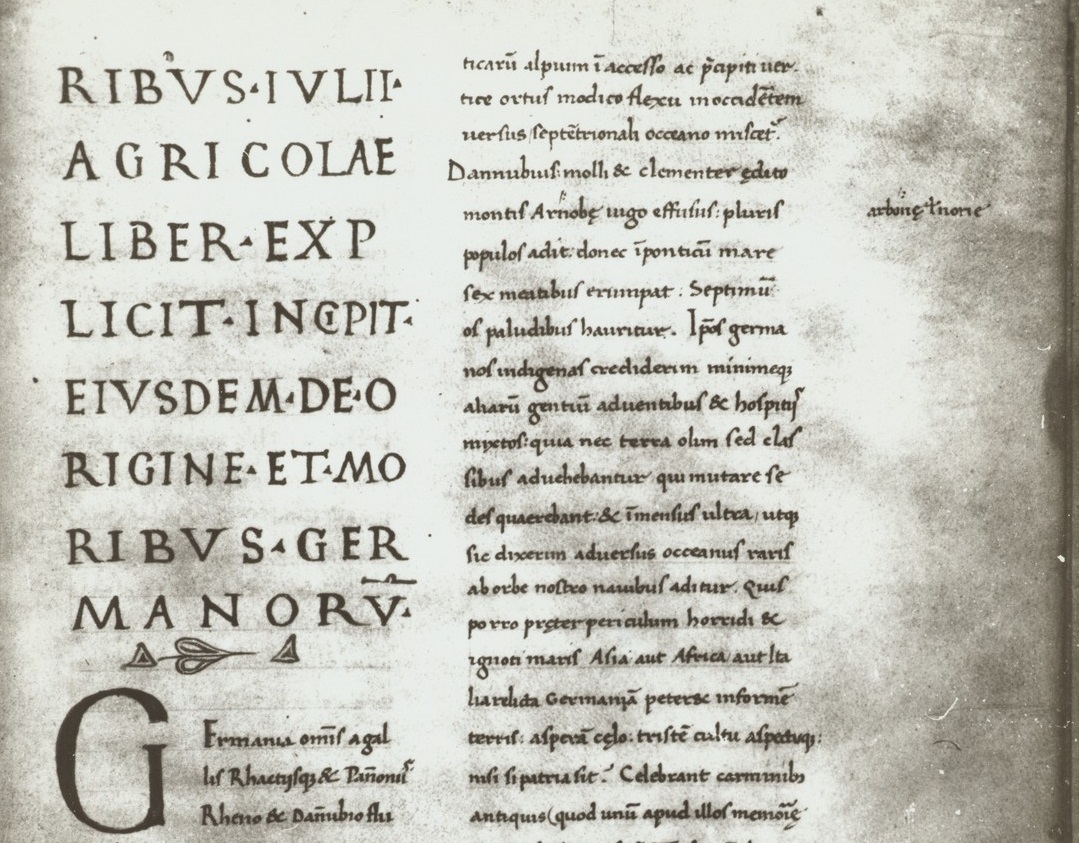

Image: The first page of the Aesinas manuscript of Tacitus’s Germania. View the codex here.

- (PART%203)\%22>(PART%203)\%22>(PART%203)\%22>The%20final%20installment%20in%20our%203%20pt%20series.%20The%20team%20discusses%20how%20a%20historical%20mindset%20can%20help%20individuals%20sort%20out%20what%20information%20is%20valid%20or%20not%20%40notabattlechick&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwarroom2.armywarcollege.edu%2Fpodcasts%2Flessons-of-history-3%2F&hashtags=War_Room #WPNS #historicalmindedness" title="Share on Twitter" onclick="essb.window('https://x.com/intent/post?text=(PART%203)\%22>(PART%203)\%22>(PART%203)\%22>(PART%203)\%22>The%20final%20installment%20in%20our%203%20pt%20series.%20The%20team%20discusses%20how%20a%20historical%20mindset%20can%20help%20individuals%20sort%20out%20what%20information%20is%20valid%20or%20not%20%40notabattlechick&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwarroom2.armywarcollege.edu%2Fpodcasts%2Flessons-of-history-3%2F&hashtags=War_Room #WPNS #historicalmindedness','twitter','74108552'); return false;" target="_blank" rel="noreferrer noopener nofollow" class="nolightbox essb-s-bg-twitter essb-s-bgh-twitter essb-s-c-light essb-s-hover-effect essb-s-bg-network essb-s-bgh-network" >

What if General X writes about a wartime event that occurred which he wasn’t present at (and it contains a lot of erroneous information) but has his people (who weren’t there either) put together the information about this same event. He “blesses it” and publishes it as more or less an after-action report, then wordsmiths it and republishes it as his own in a book that he later writes? His later interviews reinforce the various errors in this particular event as there were few U.S. forces present. The errors become repeated so often that fiction becomes fact, especially since he’s a general (and, after all, he must surely know).

There is also a problem when someone writes to a historian explaining certain events that he missed (or got wrong) in his book which the historian doesn’t attempt to consider, much less address, when the revised edition is published. Is it personal biases or is it running with the herd?

This same type of thing also seems to also occur in fictional accounts of wartime events. If they are especially outrageous, they are almost surely to be “visual humanities,” much like the Burns’ pseudo-history of the Vietnam War that was 10 years in the making, etc. In these cases, the historian seems to be the director and movie studio who (in typical Hollywood fashion) are more concerned with making a profit and taking a slap at the military is almost always good for business.