It is striking how much difficulty the United States has had converting its tactical advantages into clear strategic ‘Wins’ in the post-Cold War period

The next Whiteboard tackles a thorny issue where there is much disagreement. We polled faculty, students, and academics from around the country for their views about the U.S. military’s proficiency in tactics versus strategy. What we got back were disparate views on what words like tactics, strategy, and proficiency mean; and some very provocative views on what it implies for the military and the nation to prepare to fight and win the next war.

The deadline for the responses is now past and we are no longer accepting submissions. Please stay tuned for the release of the top responses we received.

Some analysts claim that the United States is tactically proficient, but strategically deficient. How sound is this critique?

1. Tami Davis Biddle, Professor of National Security Affairs, U.S. Army War College

At times in its past the US has achieved strategic proficiency. But there are many influences today that privilege tactics over strategy. As US military institutions became increasingly professionalized, they became proficient at the tactical level. Tactical shortcomings are obvious and costly—and military institutions are loath to accept risk in this realm. Processes and promotion systems are structured to reward superior performance that is easily discerned and measured (for instance at the National Training Center). Tactical work has a limited number of variables; this makes for fewer surprises and complexities. At the strategic level, by contrast, variables abound—as do surprises and complexities.

The biggest challenge at the strategic level, however, is the need for a clear, viable political objective (or ‘end,’ in the ‘ends-ways-means’ framework). In the US, such an objective must be agreed upon and pursued through collaboration between elected officials and military professionals—groups that have very different cultures, styles, and incentives. Often, elected officials either will resist defining ‘ends’ clearly, or will assume that they can be attained easily and quickly. And, since the advent of the all-volunteer force it’s been easier to send troops to war without a clear strategic aim.

Americans are often victims of their own optimism. In situations where decision-makers perceive real but limited stakes, they’ll often low-ball their original investment. When this proves insufficient to achieve the aim, they face an unpleasant choice between pulling out or doubling down and over-spending relative to the stake. Americans also “mirror-image”: they assume that others share their interests. In recent decades we have fallen victim to this costly error when trying to support allies (in Afghanistan and Iraq) against insurgencies. For many reasons, an ally’s interests will not align fully or easily with our own, despite our fervent wishes and expectations.

2. Lieutenant Colonel Shanon Anderson, U.S. Air Force, Graduate, U.S. Army War College Class of 2018

Tactically proficient? Yes, for now, but we will continue to be challenged by budgetary restraints and technological game changers.

Strategically deficient? Yes, but not as a measure of strategic proficiency relative to adversaries. Rather, “strategically deficient,” means the U.S. strategy has lacked qualities or elements necessary to achieve U.S. goals with suitable effectiveness and efficiency. While clearly a subjective assessment, U.S. military strategists and historians have documented avoidable strategic errors in our history that have led the U.S. to fall short of even explicit goals. Leveraging some of their work, how can military strategists fill Bernard Brodie’s intellectual no-man’s land, clear Collin Gray’s strategy gap, and overcome Rosa Brooks’ civ-mil version of the chicken-and-egg problem? I propose we start with two sub-questions:

- When working wicked problems with undetermined U.S. policy, do U.S. military strategists need to: 1) break from Huntington’s purist approach and provide other than strictly military options, or 2) break from Operational Art and Design doctrine that requires defined end states?

- How might military strategists more closely and more effectively integrate with the interagency to identify, evaluate, and recommend strategic options that fully synchronize all instruments of power?

3. John Schuessler, Professor of International Affairs, Bush School, Texas A&M University

There is certainly something to this critique. At the tactical level, it is difficult to find any peer of the United States when it comes to head-to-head combat. There is a lively debate about the sources of the United States’ military effectiveness: namely, is it mass and materiel or the skill with which force is employed that accounts for the United States’ outsized advantage on the battlefield? Few contest that the United States has had such an advantage, however.

At the same time, it is striking how much difficulty the United States has had converting its tactical advantages into clear strategic “wins” in the post-Cold War period. This has been most painfully evident in the ongoing Afghanistan War, where the United States encountered few obstacles in deposing the Taliban regime and scattering Al Qaeda but has been frustrated ever since in its attempts to leave behind a government stable and strong enough to keep those threats at bay on its own. Similar questions linger over the fate of Iraq, recent progress against ISIS notwithstanding.

Perhaps most remarkable of all is that the United States’ grand strategic position has been so well insulated from this disconnect between tactical strength and strategic weakness. After all, the United States has had to endure this string of strategic frustrations while the undisputed “unipole” in the international system. Seen from this perspective, victories in places like Afghanistan and Iraq are best seen as luxury goods, not necessities, which is exactly why the United States has not mobilized its full power to achieve them. Over the medium and long term, the United States’ grand strategic position will be affected much more by shifts in the distribution of power—especially the rise of China—than the strategic frustrations encountered when tactical strength is not sufficient to produce a favorable political outcome.

Too much focus on tactics has led the United States to lose sight of the forest for the trees

4. Colonel Celestino Perez, U.S. Army, Professor of Military Strategy, U.S. Army War College

The claim that the U.S. military is tactically proficient yet strategically deficient rests on unhelpful distinctions regarding military expertise and politics. The conventional view equates tactical proficiency with ordnance delivery; i.e., those activities required to put “steel on target.” The conventional view treats strategy as the realm of high-level politics wherein heads of state, cabinet members, diplomats, and top military leaders deliberate, specify, and advance a polity’s interests. Hence, military expertise is, at the tactical level, ordnance delivery and, at the strategic level, proffering advice about ordnance-delivery options. The foregoing understanding is coterminous with the United States’ successive bouts of strategic discontent.

Attempts to explain strategic misadventures tend to feature the failure to apply due diligence to political factors, including (i) the lash-up between military gains and political outcomes and (ii) granular appreciation of the environment’s sociopolitical, economic, cultural, and ethical dynamics. Gideon Rose, Nadia Schadlow, Linda Robinson, Richard Hooker, Raymond Odierno, the Joint Staff, and I have leveled stinging yet friendly critiques of our strategic performance…albeit with no organizational response apart from the ostrich effect. In fact, the military has redoubled its embrace of ordnance delivery, which—while integral to the profession of arms—is incomplete and, really, ethically problematic. Military expertise must respect the fact that politics goes all the way down and, as a consequence, military professionals must cultivate political literacy. We should strive—at all ranks—to be not merely managers of violence, but experts in violence. This means becoming experts in how political violence arises, maintains, morphs, and dissipates. Finally, it means cultivating the ability to discern—in the wake of military intervention—when satisfactory political outcomes are aborning…and when they are in danger of slipping away. Our teachers? Séverine Autesserre’s emphasis on the local and Elinor Ostrom’s emphasis on the pathologies of collective action.

5. Janae Cooley, U.S. Department of State, Graduate, U.S. Army War College Class of 2018

To achieve and maintain a competitive advantage internationally, foreign policy and national security leaders need to be strategic thinkers. However, two of the agencies responsible for developing and implementing national strategy–the U.S. Departments State and Defense–have each been found wanting by their respective employee advocacy organizations with regard to training for this strategic leadership role.

The American Foreign Service Association (AFSA), the Foreign Service’s professional representation entity, and the Association of the United States Army (AUSA), the Army’s primary advocacy group, have each identified gaps in their service’s respective training curricula designed to teach the skills needed to lead successfully at the strategic level.

Learning how to think strategically is challenging. Developing skills such as synthesis, judgment, and receptiveness to divergent ideas takes time. Strategic leaders need to be good at critical and creative thinking, policy analysis, and systems understanding. They must be able to scan the environment and synthesize ever-changing variables that impact the international complex adaptive system in which the U.S. operates. These skills are distinct from those needed to excel tactically.

These skills are perishable. They need to be practiced regularly. At what point on the career path should they be taught? Does the work environment support practicing and honing these skills?

Just as Generals and Ambassadors need to be “grown,” strategic leaders must also be grown and cultivated. The process requires time and sustained effort. It also takes an operating environment that wholeheartedly supports the practice and continual development and refinement of such skills. There are numerous reports that highlight training gaps and propose ways to address them. To “grow” strategic leaders who are proficient in the required skill set, the U.S. Government needs to commit the time and resources required for the training process to be effective.

6. Jayita Sarkar, Professor of International Relations, Boston University and non-resident fellow with the Stimson Center’s South Asia Program

The United States is anything but strategically deficient. The strategy — ‘grand’ or moderately long-term— is to ensure American primacy abroad through military, diplomatic, political and economic means. Whether it is to ‘speak softly and carry a big stick,’ to use the big stick, or to promote Wilsonian (later, neoliberal) democratic peace, the ultimate goal is to maintain American primacy in the international system through expansion of US global power abroad.

Where U.S. policymakers and military operators have faced most challenges is at the tactical level— unknown terrains, protracted complex conflicts, and implementing the right lessons of past successful warfighting in the wrong war. First of all, it is hard to be tactically proficient all of the time. Tactical proficiency more often measured through wins in the battlefield and building successful coalitions outside of the battlefields in faraway lands is intensive— in terms of labor, capital and knowledge, and hence, expensive.

Second, it is likely that too much focus on tactics has led the United States to lose sight of the forest for the trees. According to Mara Karlin, the challenges that the United States experienced over the past 70 years in building militaries in weak states, is owing to the misguided American focus on training and equipment of local militaries, otherwise considered important tactical components for reduced direct American military involvement abroad while protecting US interests. Instead, she argues, the emphasis must be on the character of the involvement of the US military while tackling troublesome external actors in and around those weak states.

Third and finally, the apparatus of US foreign and military policies suffers from conflict and inertia at the interagency and inter-service levels making it ever harder to implement sound strategies in a tactically proficient way each time.

HAVE SOMETHING TO ADD?

How good is the U.S. Army at developing strategic leaders? Be a part of the follow-on Whiteboard. Send your 300 word (maximum, and we mean it!) response to andrew.a.hill13.civ@mail.mil, cc: thomas.p.galvin.civ@mail.mil by August 31, 2018. Remember to include the Subject: Whiteboard #3.

The views expressed in this Whiteboard are those of the contributors and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, U.S. Army, or Department of Defense.

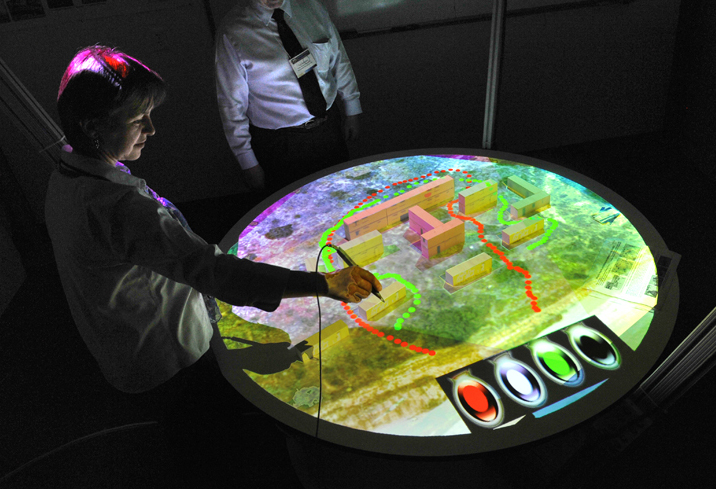

Photo: Amela Sadagic, a research associate professor, demonstrates the virtual sand table for urban warfare operations training rehearsals during the MOVES 9th Annual Research Summit July 22, 2009, in Monterey, Calif.

Photo Credit: U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class John Fischer

Other Releases in the “Whiteboard” series:

- THE ADMINISTRATION’S TOP FOREIGN POLICY PRIORITY (A WHITEBOARD)

- AFTER 2020, WHAT’S NEXT? (A WHITEBOARD)

- IMAGINING OVERMATCH: CRITICAL DOMAINS IN THE NEXT WAR (A WHITEBOARD)

- THAT ONE MOST IMPORTANT THING: (A WHITEBOARD)

- SHALL WE PLAY A GAME?

(WARGAMING ROOM) - WAR(GAMING) WHAT IS IT GOOD FOR? (A WHITEBOARD)

- LEADERSHIP ROLE MODELS IN FICTION REVISITED: (A WHITEBOARD)

- WHAT GOOD IS GRAND STRATEGY? (A WHITEBOARD)

- THE UNITED NATIONS’ GREATEST ACCOMPLISHMENT: (A WHITEBOARD)

- LEADERSHIP ROLE MODELS IN FICTION: (A WHITEBOARD)