It was the best of times, it was the worst of times. Despite a stunning victory over Iraq during Operation DESERT STORM, the U.S. Army of the 1990s was beset by doubts about its post-Cold War mission, the challenges of deployment quite different than what it had trained for, and the need to adapt to changing societal norms. David Fitzgerald has written about all of this and more in his recent book Uncertain Warriors: The United States Army between the Cold War and the War on Terror.. He joins guest host Carrie Lee in the studio for the next installment in our special series supporting the U.S. Army War College’s Civil-Military Relations Center.

If you are a military servicemember in the 1990s your deployment was most likely a peacekeeping mission—Haiti, to Bosnia, to Kosovo, to Somalia. And those missions require something a bit different They require service members to behave differently. They require a little bit of a different ethos and there is an interesting debate within the military about that.

Podcast: Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | Blubrry | Podchaser | Podcast Index | TuneIn | Deezer | Youtube Music | RSS | Subscribe to A Better Peace: The War Room Podcast

David Fitzgerald is a Senior Lecturer in the School of History, University College Cork, Ireland. His research focuses on modern American military history and foreign policy. More specifically, he works on the history of American counterinsurgency, questions of military intervention, and on the intersections between the U.S. military and broader American society and culture. He is the author of Learning to Forget: U.S. Army Counterinsurgency Doctrine from Vietnam to Iraq (Stanford, 2013), Militarization and the American Century: War, the United States and the World since 1941 (Bloomsbury, 2022) and Uncertain Warriors: The United States Army between the Cold War and the War on Terror (Cambridge, 2023).

Carrie A. Lee is an associate professor at the U.S. Army War College, where she serves as the chair of the Department of National Security and Strategy and director of the USAWC Center on Civil-Military Relations. She received her Ph.D. in political science from Stanford University and a B.S. from MIT.

The views expressed in this presentation are those of the speakers and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, U.S. Army, or Department of Defense.

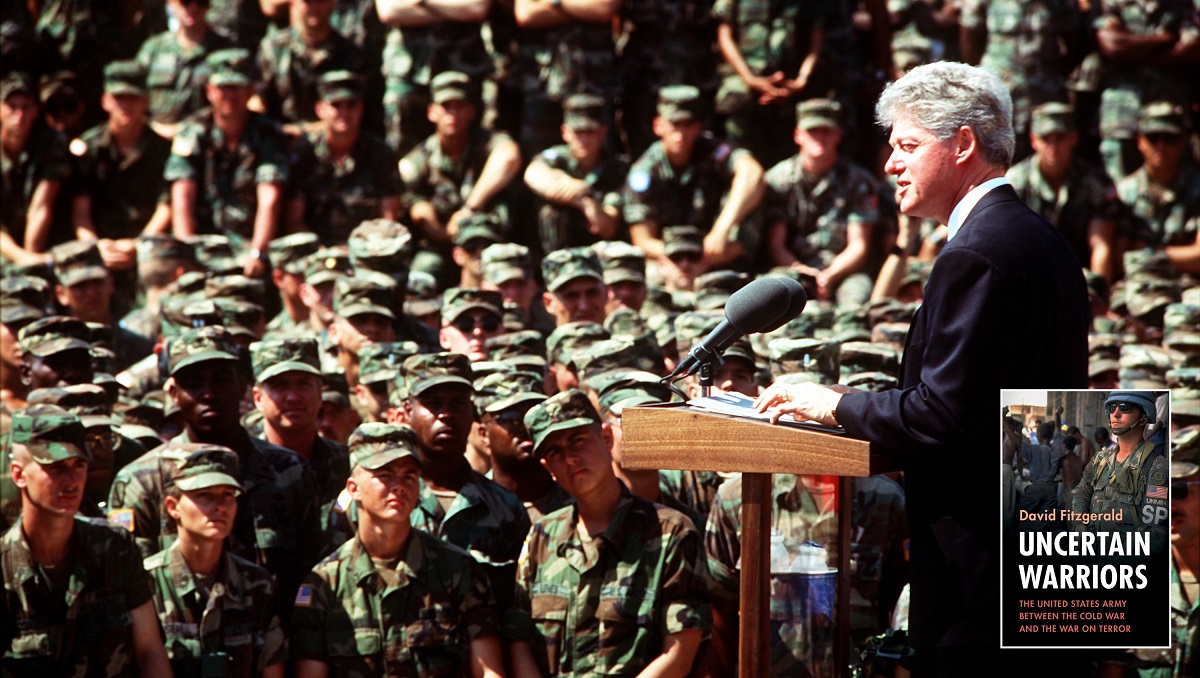

Photo Description: President William Jefferson Clinton speaks to the troops at Warrior Base camp in Port-au-Prince. President Clinton flew to Haiti to address and meet with troops of the Joint Task Force and attend the United Nations transition ceremony, March 31, 1995.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of the National Archives, photographer unspecified.

Some of the most dramatic changes — in national security thinking and strategy (which will effect the Services in the period between the end of the Cold War and the War on Terror?) — are shown below:

“Throughout the Cold War, we contained a global threat to market democracies; now we should seek to enlarge their reach, particularly in places of special significance to us. The successor to a doctrine of containment must be a strategy of enlargement — enlargement of the world’s free community of market democracies. During the Cold War, even children understood America’s security mission; as they looked at those maps on their schoolroom walls, they knew we were trying to contain the creeping expansion of that big, red blob. Today, at great risk of oversimplification, we might visualize our security mission as promoting the enlargement of the ‘blue areas’ of market democracies. The difference, of course, is that we do not seek to expand the reach of our institutions by force, subversion or repression.” (From then-National Security Advisor Anthony Lake’s 1993 “From Containment to Enlargement” — a precursor to and introduction of what would soon become then-President Bill Clinton’s signature “Engagement and Enlargement strategic document.)

“Since the 1990s the focus of American international security policy has been focused on creating conditions for extending zones of security and prosperity to other states under the theory that ‘political as well as economic globalization would make the world safer — and more profitable — for the United States.’ Consequently, the United States saw expansion, rather than retraction, of American military presence around the world.” (See the 2016 edition of the book “Exporting Security: International Engagement, Security Cooperation, and the Changing Face of the US Military” by U.S. Naval War College Professor Derek S. Reveron; therein, see the bottom of Page 2 of the Introduction chapter.)

From Andrew Bacevich’s — 1999 — “Policing Utopia: The Military Imperatives of Globalization:

“Based on recent events, skeptics may be forgiven for viewing such optimistic expectations as fanciful. Certainly Pentagon planners do not stay up nights worrying that globalization will put the Department of Defense out of business. On the contrary, they understand that pressing for an open world and enforcing its rules will generate a plethora of new military requirements. In the first decade of the post-Cold War era, with its myriad crises, interventions and emergency deployments, they have experienced this phenomenon at first hand. In a larger though barely acknowledged sense, that experience revalidates century-old military lessons derived from a time when the United States liberated (and occupied) Cuba and shouldered the responsibility for uplifting ‘Little Brown Brother’ in the western Pacific. Crusades mean work for soldiers.

Full Spectrum Dominance

Yet rather than acknowledging—and obliging its political masters to acknowledge—the inevitable consequences of enforcing conformity on a complex, dynamic and sometimes recalcitrant world, the military has fashioned a utopia of its own. Unmoved by visions of self-regulating peace and prosperity, the defense establishment seeks to stifle opposition to the American version of globalization by institutionalizing U.S. military supremacy. The Pentagon blueprint for the future, a document known as Joint Vision 2010, has established for itself a singularly grandiose goal: ‘the ability to win quickly and overwhelmingly across the entire range of operations, or in other words, ‘Full Spectrum Dominance.’ That full spectrum does not ignore conventional war and the threat posed by weapons of mass destruction. But it pays particular attention to the security agenda of the globalization project, now grouped under the rubric of ‘asymmetric threats’—terrorists, criminals, religious crazies, two-bit strongmen with big ambitions, anarchy-minded hackers and unscrupulous scientists peddling weapons secrets to make a buck.”