[T]he Army rarely surveys as a group its general officers that were responsible for combat operations…

The U.S. Army, as well as the other military services, spends considerable resources each year to assess operational performance. It does so through lessons learned programs, after action reviews, official histories and several other analytical mechanisms using its in-house expertise or hiring others to do so. Yet, the Army rarely surveys the general officers responsible for combat operations, asking them as a group for their assessment of forces, strategy, tactics, and other crucial subjects; these topics remain relevant as scholars, policymakers, military leaders and others strive to understand wars, especially the recent ones in Iraq and Afghanistan.

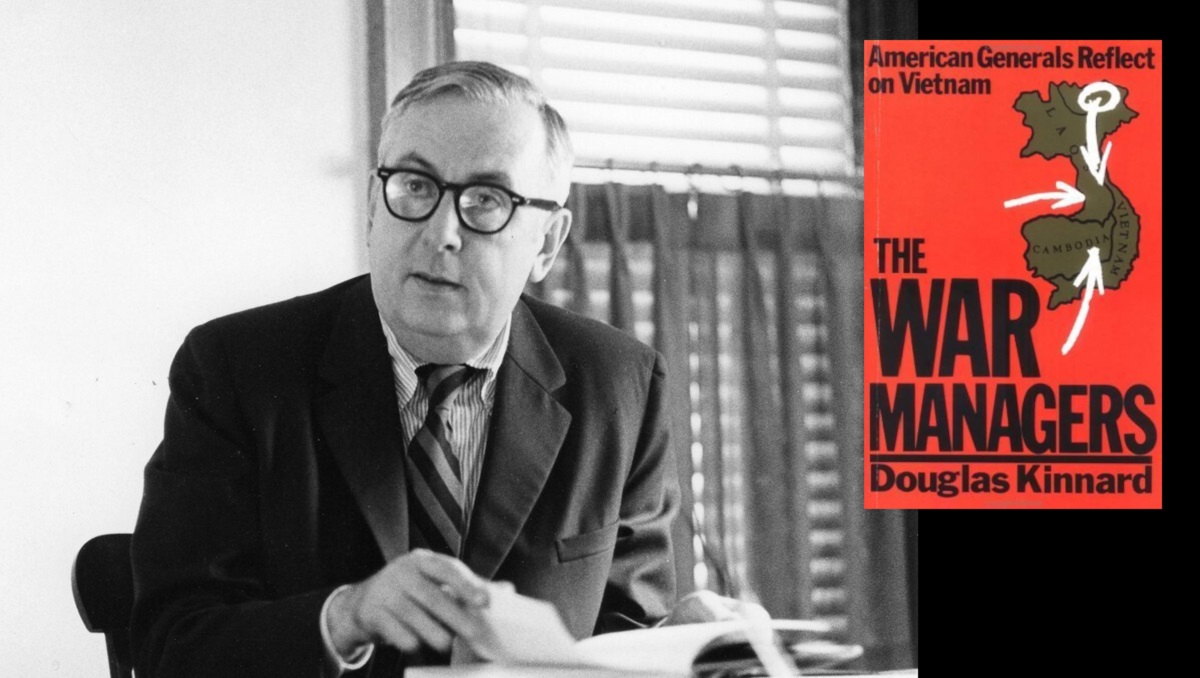

It is this type of assessment that retired U.S. Army Brigadier General Douglas Kinnard performed in 1974, but as a professor of political science at the University of Vermont, a year after the final U.S. combat units withdrew from South Vietnam and before the war ended a year later. The result was the publication of his findings in the controversial book The War Managers, first published in 1977, and because scholars considered it to be a classic study of the war, Naval Institute Press republished it in 2007. The reissuance after three decades led to a rediscovery of his work by serving U.S. military officers who deemed it an important work for professional development, and scholars who praised it for its objectivity and high-quality analysis as well as the useful data and the anonymous respondent commentary it included. Reviewers of the thirtieth anniversary edition asserted that generals leading U.S. forces in the Iraq should read the book as a study in how a war could go wrong.

Kinnard’s credentials as a soldier and a scholar were impressive. He was not, an “egg-head academic,” but “had mud on his boots in three wars.” A 1944 graduate of the U.S. Military Academy, Kinnard saw combat in World War II as an artillery officer; in the Korean War as an intelligence and operations officer; and two tours of duty in South Vietnam. The first tour, 1966-67, as a colonel, where he was chief of operations analysis in the J-3, U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV). He returned for the second tour in May 1969 as commanding general of II Field Force (equivalent to a corps) Artillery and subsequently, chief of staff of the II Field Force. After retiring from the Army in 1970, he entered Princeton University, where he earned a doctorate in politics in 1973.

Kinnard took a leave of absence from teaching in 1983 to become the U.S. Army’s chief of military history in Washington, where he shaped the Army’s history program both in terms of subjects and methodology. He later taught at the Naval War College and the National Defense University, developing future leaders. As retired Brigadier General John Eisenhower, Ike’s son and Kinnard’s friend said of him, his “military background and political knowledge gave him a unique vantage point as a scholar and allowed him to look beyond the surface of key issues.” These attributes were aptly on display in The War Managers.

Kinnard believed that it was critical to “reassess the war from the point of view of its Army General Officer managers while they were still available and before their memories of the war faded” (vii). More importantly, he believed it vital to understand a war he believed had been a “disaster” (vii) and to learn from it for the benefit of future U.S. policymakers, military leaders, diplomats, scholars and the American public.

To that end, Kinnard sent a 60-item attitudinal survey to 173 Army generals who commanded in South Vietnam from 1965 to 1972. He limited the respondents to generals who led combat formations from separate infantry brigades and field force (corps equivalent) artillery as brigadier generals to the four-star generals that commanded U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam. He fashioned the questions to draw on their direct experience, and he guaranteed that their responses would be anonymous.

In September 1977, a month before the public release of his book, the New York Times published an article about his findings with the title: “Generals in Survey Assail Vietnam War.” The first sentence of the article baldly laid out the most telling conclusion; the majority of generals who served in the war said that in retrospect that the United States “should have avoided involvement.” The article continued by describing some of the other findings, both statistical summaries and individual comments. Beyond that, however, there was no publicity regarding the forthcoming book.

A rigorous and honest appraisal was Kinnard’s purpose, and he was satisfied with the outcome: 64 percent of the contacted officers completed the questionnaire and many offered pages of comments. In addition to the statistical results, Kinnard delved deeper with follow-up interviews of a select group of the generals who had responded. He also conducted research using published U.S. government reports, secondary sources, and material at the U.S. Army Center of Military History to refine his analysis and offer a trenchant summary of the conflict’s major events.

The book, less than 200 pages long, mirrors the questionnaire and is divided into seven chapters, including an introduction and conclusion, which discuss U.S. objectives, the conduct of the war, the enemy’s strategy and tactics, the U.S. military advisory and pacification efforts, personnel issues and media relations, and ultimately war termination. However, it was the starkness of the statistical findings that created the controversy. With respect to the war’s objectives, 68 percent of the respondents indicated that they were “not as clear as they might have been” or “rather fuzzy—needed rethinking as war progressed,” (24) a criticism of Washington’s poor guidance. Less than half believed the military objectives were attainable before 1969 when President Richard Nixon introduced his “Vietnamization” policy, (31) whereby U.S. combat troops would gradually withdraw and the South Vietnamese military would be solely responsible for the conflict. Most of the generals agreed that the concept was sound but occurred too late in the war (144).

A majority claimed that the execution of the search and destroy tactics “left something to be desired.”

As to tactics, defined as “search and destroy,” 58 percent held that the concept was either “not sound” or “sound when first implemented, not later” (45). A majority claimed that the execution of the search-and-destroy tactics “left something to be desired.” As Kinnard told the Times reporter, “I just can’t imagine a World War II general saying the tactics of the war left something to be desired.”

The generals’ assessment of the future of the South Vietnamese Army (ARVN) was dismal with respect to the success of Nixon’s Vietnamization policy and U.S. efforts to improve that force (153) in terms of “leadership, logistics, tactics and troop morale”: only 8 percent saw it as a “very acceptable fighting force” by 1974, when the survey was conducted, and another 25 percent doubted it could hold against a “firm push” from the enemy. However, 57 percent thought ARVN was “adequate” and believed that their “chances of holding [against the enemy] in the future better than fifty-fifty,” which proved overly optimistic given that South Vietnam lost the war the next year. As to the ARVN generals, the results were mixed. Their U.S. counterparts ranked ARVN generals based on personal observation during their tour of duty, “fair to good,” 57 percent, but one-third deemed them “inadequate” (87).

The U.S. generals, on the other hand, rated their former adversaries more favorably. The Viet Cong, the military arms of the National Liberation Front, which was eviscerated in the costly 1968 Tet offensive, was rated as a force of “skilled and tough fighters” by 57 percent of the respondents (67). As for the North Vietnamese Army, 44 percent considered it to be “a skilled and tough force,” while another 32 percent deemed it sufficient for the strategy and tactics that they used (67).

Some issues were emotionally painful. Regarding body counts, one measure of effectiveness used by MACV, 61 percent of the respondents indicated that the counts were “often inflated” (75). One general wrote that “the immensity of the false reporting is a blot on the honor of the Army” (75). Another measure, the kill ratio, also came under harsh criticism: 55 percent believed it to be a “misleading device to estimate progress” (74).

But the most stunning response came with the penultimate question about whether the war was worth the effort when one considered the casualties, the impact on American society and its military, and the political turmoil it caused. A quarter believed that the war should not have gone beyond the advisory effort, and another 28 percent said it was not worth the effort. Only 14 percent said the results “were worth the effort” and 25 percent believed they were “worth the effort, but the effort should have been greater.” Eight percent offered no response (153-4).

Kinnard’s findings allegedly caused consternation in the Army. They would soon alarm the one person who would feel personally beset—General William C. Westmoreland who had commanded U.S. forces in South Vietnam from 1965 to 1968. That moment came on October 7, 1977, after The War Managers had been published, when Westmoreland and Kinnard appeared together on ABC network’s “Good Morning America” to discuss Kinnard’s findings. After the appearance, Kinnard gave Westmoreland a copy of the book. Over the next week, Westmoreland telephoned Kinnard several times, pestering him about which general made a particular comment. Kinnard refused to snitch. A week later, the copy Kinnard gave Westmoreland arrived in the mail “with his notes written on nearly every page.”

The Westmoreland saga, however, continued. In January 1982, Westmoreland sued the CBS network for libel and $120 million in damages, contending that a documentary the network produced implied that Westmoreland had conspired to “suppress and distort intelligence … to substantiate his optimistic reports on the progress of the war.” A federal court, on behalf of CBS, issued a subpoena in September 1983 for Kinnard’s questionnaires so that CBS could obtain material that supported its argument that it had not defamed Westmoreland. Kinnard hired lawyers to fend off the subpoena, arguing the questionnaires were protected by the First Amendment.

Kinnard’s book would be widely reviewed throughout 1978 in scholarly journals for sociology, history and political science, but also in professional military periodicals. Some reviews were favorable, others less so, but even those who criticized his methodology or other aspects, believed his work important for the data and revelations it provided. The reviews after its reissuance were even more admiring.

But if a book is to be pulled off the dusty shelves, then there must be a larger purpose. In this case, it is learning lessons from history, and that depends upon, as the military historian Allan Millet said, “what sorts of questions one asks of the past as well as a willingness to reexamine both the questions and the answers.” The War Managers asked pertinent questions and provided some answers based on empirical data, analysis and a historical summary of the war’s context. In doing so, it helped advance an early understanding of what happened in Vietnam and why through the opinions of the Army’s senior combat leaders, but it also provided insight into the conflict’s impact on the institution’s proficiency and values. Today, perhaps there is a retired general who served in Iraq or Afghanistan that is willing to ask peers for their candid views on those conflicts: the strategy devised, the tactics employed, and the measures used to determine progress. There are certainly more questions to be asked of them as well as presidents and their advisors. Maybe there is now a willingness to confront the answers, and not, as Samuel Huntington advised after the Vietnam War: “It is conceivable that our policy-makers may best meet future crises and dilemmas if they simply blot out of their minds any recollection of this one.”

Frank Jones is a Distinguished Fellow of the U.S. Army War College where he taught in the Department of National Security and Strategy. Previously, he had retired from the Office of the Secretary of Defense as a senior executive. He is the author or editor of three books and numerous articles on U.S. national security.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

Photo Description: Retired Army Brig. Gen. Douglas Kinnard, who was decorated for combat service in Vietnam and later conducted a high-profile survey the results of which were published in the book The War Managers, died July 29, 2013 at a hospital in Chambersburg, Pa. He was 91.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of University of Vermont

“…the copy Kinnard gave Westmoreland arrived in the mail “with his notes written on nearly every page.”

This marked up copy of the book would be really something to read. I wonder what archive it is in if it is still around.

Incidentally, this book was first re-published in the 80s by Avery Publishing. I still have my copy purchased at the Cadet Book Store.

I met General Kinnard when I was a member of the general staff of the Saigon Support command at Long Binh in 1970. I was responsible for an element of the Cambodian operation and my opinions as a first lieutenant were treated by General Kinnard with more respect that they probably deserved. A great man.

Can you kiss ass bettter than this?

I am very happy to read this. This is the kind of manual that needs to be given and not the random misinformation that’s at the other blogs. Appreciate your sharing this greatest doc.

Given that the kind of wars that the U.S./the West embarked upon post-the Old Cold War; given that these were of a “revolutionary” and/or of a “transformative” nature (and, thus, were ultimately designed to transform states and societies such as Afghanistan and Iraq more along modern western political, economic, social and value lines):

“Today America and our friends and allies must commit ourselves to a long-term transformation in another part of the world: the Middle East. A region of 22 countries with a combined population of 300 million, the Middle East has a combined GDP less than that of Spain, population 40 million.” (See the second paragraph of the August 7, 2003 Washington Post article “Transforming the Middle East” by Condoleezza Rice.)

” … In Afghanistan and Iraq too, we represented revolutionary change. So, perhaps we should read Mao and Che Guevara instead of Thompson in order to find the appropriate lessons of how to achieve large-scale societal change through limited means? That is what we are after, in the end. And in this coming era, where we are pivoting away from large-scale interventions and state-building projects, but not from our fairly grand political ambitions, it may be worth exploring how insurgents do more with little; how they approach irregular warfare, and reach their objectives indirectly.” (See the paragraph beginning with “Dhofar, El Salvador and the Philippines” in the Small Wars Journal article “Learning From Today’s Crisis of Counterinsurgency” — an interview by Octavian Manea of Dr. David H. Ucko and Dr. Robert Egnell.)

Given this such “revolutionary”/”transformative” political objective of the U.S./the West post-the Old Cold war, might we say that:

a. The overall “revolutionary”/”transformative” job that America’s “war managers” had in Greater Middle East of late, these:

b. Were similar to the overall “revolutionary”/”transformative” job that Soviets/the communists “war managers” had in the Old Cold War of yesterday? (In the Soviets/the communist’s Old Cold War case, of course, the overall goal was to transform various states and societies more along Soviet/communist political, economic, social and value lines).

If such indeed this is the case, then what (specific to “revolutionary”/”transformative” goals) questions should be asked of America’s recent “war managers,” and what (specific to “”revolutionary”/”transformative” goals) answers might America’s recent “war managers” give in response to such questions?

(“Revolutionary”/”transformative” questions and answers of America’s recent “war managers” which could, indeed, be made into a very interesting and informative report and/or book?)

From the final paragraph of our article above:

“In this case, it is learning lessons from history, and that depends upon, as the military historian Allan Millet said, ‘what sorts of questions one asks of the past as well as a willingness to reexamine both the questions and the answers.’ ”

Re: this such thought in the final paragraph of our article above, is it possible that I have — by emphasizing the “revolutionary”/the “transformative” nature of our recent wars — properly suggested what “sort” of questions should be asked of (a) our “war managers” and of (b) our recent history?

Given the premise that the questions that America’s “war managers” entertained – from a retired general officer after the Vietnam War — given that these such questions (and the answers thereto) — to be properly understood and considered — had to be then — and indeed still have to be today — considered within the larger context of the Old Cold War of yesterday.

(Old Cold War of Yesterday: The Soviets/the communists, post-World War II, seek to achieve “revolutionary”/”transformative” political, economic, social and value change [more along Soviets/communist lines] — both in their own home countries and abroad. “Conservative”/status quo-loving individuals and groups [both at home the Soviet Union and abroad] — and “conservative”/status quo-loving states and societies — their power, influence, control, etc., thus commonly threated by these such highly unwanted “revolutionary change” initiatives — seek to “contain,” and/or to “roll back,” the Soviets/the communists and their such — highly unwanted by many — “revolutionary changes.”)

Given this such premise, then must not the questions that America’s “war managers” might entertain today — for example from a retired general re: the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan of late — must not these such questions (and the answers thereto) — ALSO to be properly understood and considered — have to — today and forever more — be considered within the larger context of the New/Reverse Cold War of today?

(The New/Reverse Cold War of Today: The U.S./the West, post-the Old Cold War, seeks to achieve “revolutionary”/”transformative” political, economic, social and value change [more along market-democracy lines] — both in our own home countries and abroad. “Conservative”/status quo-loving individuals and groups [both here at home in the U.S./the West and there abroad] — and “conservative”/”status quo-loving states and societies — their power, influence, control, etc., thus commonly threated by these such highly unwanted “revolutionary change” initiatives — seek to “contain,” and/or to “roll back,” the U.S./the West and our such — highly unwanted by many — “revolutionary changes.”)

Thus, in both such cases (the war in Vietnam and the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan) — to be able to properly understand and consider the questions posed to “war managers” — and to be able to properly understand and consider the answers these “war managers” give thereto — this must be done — in both such cases — with proper consideration of the larger “war” context — and the political objectives of the various major “warring” parties — which prevailed at these such separate times?

Consider the following quoted items (from the “Classical Insurgency” section of David Kilcullen’s “Counterinsurgency Redux”) as an example of how embracing the New/Reverse Cold War context — which I suggest immediately above — might (a) help us to better “frame” the questions that we might ask of our Iraq, Afghanistan, etc., “war managers” and might (b) help us to better understand the answers that our such “war managers” might give to these such questions:

“Classical counterinsurgency theory posits an insurgent challenge to a functioning (though often fragile) state. The insurgent challenges the status quo; the counterinsurgent seeks to reinforce the state and so defeat the internal challenge. … ”

“Similarly, in classical theory, the insurgent initiates. Thus, Galula asserts that ‘whereas in conventional war, either side can initiate the conflict, only one — the insurgent — can initiate a revolutionary war, for counterinsurgency is only an effect of insurgency.’ … ”

“But in several modern campaigns — Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan and Chechnya, for example — the government or invading coalition forces initiated the campaign, whereas insurgents are strategically reactive (as in “resistance warfare”). … ”

[Likewise,] “Politically in many cases today, the counterinsurgent [the U.S./the West and/or our partner governments] represent revolutionary change, while the insurgent fights to preserve the status quo of ungoverned spaces, or to repel an occupier — a political relationship opposite to that envisaged in classical counterinsurgency.” (Items in brackets here are mine.)

Thus, by using my New/Reverse Cold War suggestion in my comment immediately above — this, to better “frame” the questions that we might ask of our “war managers” of late — we might, thereby, become better able to understand how these “war managers,” for example, had to deal with the AMAZING contradictions posed by David Kilcullen above?