In my view, the recent misguided attention paid to materials used for developing our military officers at all levels of professional military education is detrimental.

In June 2023, I was honored to attend the National Security Seminar held at the U.S. Army War College. This year’s theme for the National Security Seminar was an examination of civil-military relations. I found the week extremely rewarding, and I was amazed at the different issues that emerged related to civil-military relations in the nation. One of the issues raised was the issue of “wokeness” in the military, which has been a touchstone of the current political debates. In August 2023, news outlets ran stories about how the Chief of Naval Operations removed several books from his recommended reading list that were controversial and dealt with race issues.

This is both unfortunate and upsetting. In my view, the recent misguided attention paid to materials used for developing our military officers at all levels of professional military education is detrimental. It is stunting individual readiness and the overall ability of the military to defend our nation.

As a historian, let me present a case study over past discussions about teaching politically charged subjects and how it pertains to the U.S. military. While researching a different topic, I stumbled upon a debate that occurred at the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1934-1935 over whether cadets in a mandatory economics class should be taught about the New Deal. It was as contentious and polarizing as the modern discourse on “wokeness.” I believe this historical event can provide valuable guidance for current discussions on books and current professional military education.

Since 1802, West Point has been producing Army officers and leaders for the nation. From presidents to generals to writers to business leaders, West Point has been one of the leading institutions of higher education in the nation. However, by the end of World War I, West Point had entered a period of ennui and was more worried about the trappings of education and parade ground military and not producing military leaders that could meet the complex geo-political world the United States faced in the early 20th century. Under the leadership of General Douglas MacArthur, the superintendent after World War I, West Point began teaching more social sciences and history as a crucial part of the curriculum. MacArthur ordered the establishment of a Department of Economics, Government, and History. In 1930, the department was chaired by Lieutenant Colonel Herman Beukema (USMA Class of 1915), a distinguished artillery officer during the Mexican War and World War I. Beukema returned to West Point in 1928 to teach social studies and eventually became the head of the department in 1930. Beukema would later go on to become one of the nation’s early experts on geopolitical thought, as well as a teacher and mentor to Brigadier General George A. Lincoln and other prominent Cold War-era strategic thinkers, including General Andrew Goodpaster (the namesake for the Army’s Goodpaster fellows, a cohort pursuing doctoral studies ).

In the late portion of the fall semester of 1934, Beukema (like most professors) was trying to determine the readings for his spring semester classes. Beukema determined that cadets needed to study President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal programs because of the significant role the programs and policies were having on the nation’s economy and society in general. On November 28, 1934, Beukema submitted a routine memo requesting the temporary adoption of The New Deal in Action by Schuyler C. Wallace for use in the Economics course for fourth-year cadets (seniors). At the time, a professor would submit this type of request to the General Committee, which was an academic committee made up of nine professors representing the various departments. The General Committee would then forward their recommendation to the Superintendent for his approval.

The New Deal in Action was not written by any leftist firebrand. Wallace was an associate professor of public law at Columbia University and would have a stellar academic career, including training U.S. Navy officers for military governance in the Pacific in World War II. It is safe to say that Dr. Wallace was not advocating for radical changes in the nation’s economy in his book. Beukema stated in the memo that he had examined “a considerable number of books covering the New Deal… [and this one] presents the best and simplest factual survey of the subject.” Furthermore, Beukema reminded the General Committee and the superintendent that cadets had already examined the New Deal the past year using numerous articles and a pamphlet by Howard S. Piquet (Outline of the “New Deal” legislation of 1933). Two weeks after Beukema’s submission, the General Committee agreed to the recommendation and sent the request to the superintendent for his approval.

While the General Committee approved the request to use the book, there was some dissent among the members about the inclusion of the book (and the subject matter in general). Colonel C.C. Carter, Professor of Natural & Experimental Philosophy, felt that the Wallace book provided “a one-sided presentation, if not a partisan one.” Also, he argued that cadets should not have their first taste of economics clouded with a large amount of time dedicated to a “particular controversial phase of current events.” While Colonel Carter did feel that cadets should be educated on the issues of the day, he felt that this book was too partisan to be used at West Point. Colonel R.G. Alexander, the Professor of Drawing, wrote “I concur” on Carter’s letter with no further details. Lieutenant Colonel C.L. Fenton, the head of the Department of Chemistry and Electricity, mirrored Carter’s arguments in a memo dated December 14, 1934, where Fenton described the book as a “highly colored, incomplete presentation of one side of the question.”

As an academic and seasoned bureaucrat, Beukema addressed the criticisms of the book in a memo dated December 17, 1934, directed to the members of the Academic Board. The three-page memo provided detailed responses to the Academic Board members’ criticisms of the book. Beukema even included specific sections of the book that were critical of the New Deal. Beukema also reminded the Academic Board members that the cadets at the academy regularly studied current events “considered too important to be ignored or underestimated.” Furthermore, Beukema took offense to the Professor of Chemistry telling him (the chair of the Social Sciences Department) what to cover in the Economics class and stated that the “New Deal is a subject of study at all leading colleges and universities today.” Lastly, Beukema argued that the department had selected a book that stayed sufficiently neutral to develop a sound discussion.

Not analyzing the New Deal and its impact on the economy would be akin to not studying Reagan’s “Trickle Down Economics” in the 1980s or the economic facets of the Space Race in the 1960s.

Even though Beukema crafted an eloquent defense of the use of the book, Major General William D. Connor, the Superintendent of the Academy, denied its use because “the so-called New Deal is a live political issue and, as such, is not suitable for study or discussion in this institution. Second, the so-called New Deal is personally sponsored by the President, who is Commander-in-Chief of the Army, and whose policies are therefore not properly debatable in this institution.”

Beukema met with the Superintendent on January 2, 1935, to plead his case that you cannot teach modern economics, which Beukema argued was “wholly controlled by New Deal legislation,” without discussion of the New Deal. Major General Connor agreed to a compromise and allowed for the facts “flow[ing] from the law to be discussed in class. However, the New Deal policies are not to be the subject of debate. While Beukema did not get to use the book, he did get to teach the cadets about the New Deal.

Looking back, it’s hard to believe that Beukema had to struggle to educate his colleagues about the significance of the New Deal, which was one of the most crucial reforms in terms of government and economy during the 20th century. Not analyzing the New Deal and its impact on the economy would be akin to not studying Reagan’s “Trickle Down Economics” in the 1980s or the economic facets of the Space Race in the 1960s. Both subjects that were controversial at the time.

It is important for cadets and officers to have knowledge of current events and society to be effective leaders and soldiers in a democratic society. While some critics may have personal views on subjects, studying them does not mean being indoctrinated into a certain ideology. It is necessary for cadets and officers to understand modern social and cultural issues to lead their soldiers effectively, especially in an all-volunteer military. Military conflicts do not occur in a social and cultural vacuum, and leaders need to comprehend the causes of war. For instance, while the American Revolutionary War was primarily due to a desire for freedom in the colonies, there were also social, political, cultural, and economic undertones. In the Southern Campaign, people often chose sides for cultural reasons instead of political ones.

It is vital for military officers to have a comprehensive understanding of current events in American society in order to strengthen civil-military relations. They must be familiar with the life experiences of their soldiers to effectively lead them. Additionally, they should be knowledgeable about various political, social, and cultural movements without being influenced by them. Although the military remains nonpartisan, it is still important for them to be educated. In today’s world, where information, culture, heritage, and social media can be weaponized and used in irregular warfare, military leaders should be well-versed in traditional military science as well as understanding their own society and others.

Edward Salo, Ph.D. is an Associate Professor of History and the Associate Director of the Heritage Studies Ph.D. Program at Arkansas State University. Before coming to A-State in 2014, he spent 14 years as a consulting historian for various firms across the nation. His work has been published in War on the Rocks, The National Interest, 1945, InkStick, and by the Modern War Institute. He is also a host of the “Sea Control” Podcast, and a member of the New America Nuclear Futures Working Group.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Arkansas State University, the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

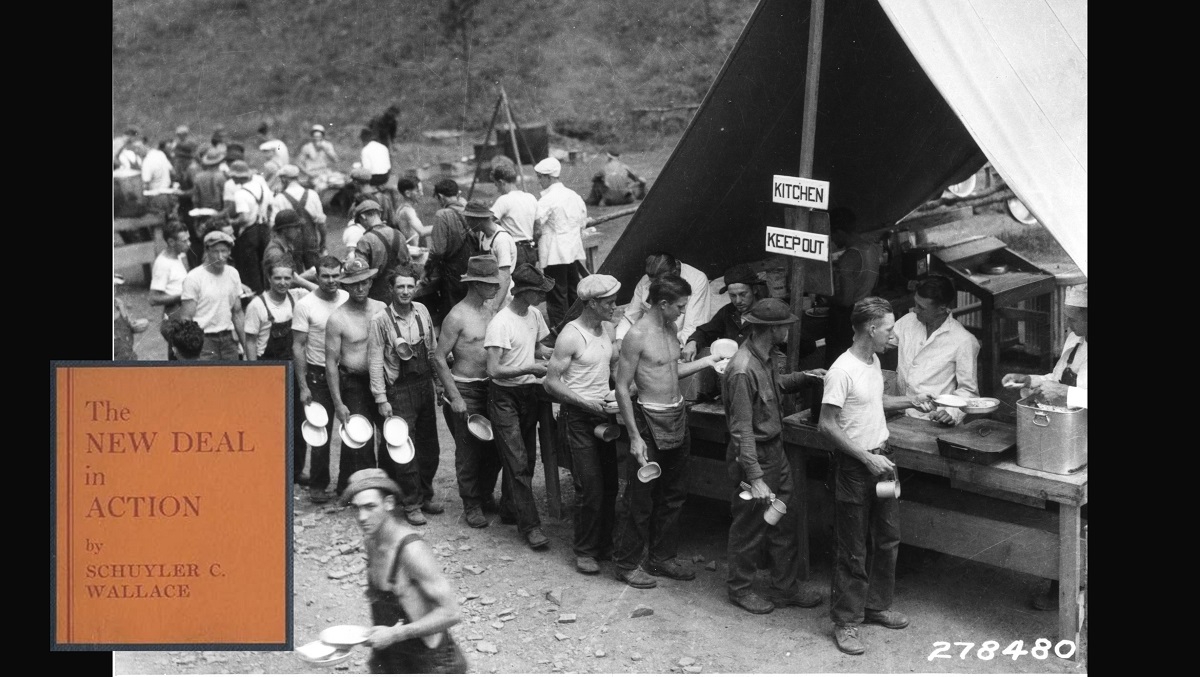

Photo Description: Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camp mess line. The Civilian Conservation Corps was created as part of the New Deal in 1933 by FDR to combat unemployment. This work relief program had the desired effect, providing jobs for many thousands of Americans during the Great Depression. The CCC was responsible for building many public works projects and created structures and trails in parks across the nation that are still in use today.

Photo Credit: USFS photo #278480 from the Gerald W. Williams Collection via OSU Special Collections & Archives

What an odd apologia.

Dr. Salos tells us that merely studying a topic is not akin to ideological indoctrination. He then goes on to explain how cultural study is necessary to enlighten soldiers as if they are strangers in their own land.

Let’s be clear: all education includes an element of indoctrination. Instructors might permit a liberal and critical inquiry. But they also dictate the accepted terms and frames of reference. This is especially true of professional military education. What is taught in a military classroom is not whimsy. It is an extension of some policy intended to shape or reproduce the military institution. And when soldiers are exposed to ‘cultural education,’ internalizing those codes becomes essential for professional recognition and advancement.

How is this not indoctrination?

An “apples and oranges” question — based on the article above:

As relates to a student’s necessary understanding of “economics,” today, (and, thus, of national security?) do such things as “race issues” (and “sex issues” also for that matter), today, “rate” as being as important — less important — and/or more important — as (from our article above) the New Deal, the Space Race and/or Reagan’s “Trickle Down Economics” yesterday?

As relates to this such question, consider the following quoted items:

” … The chief thesis of this article is that the (U.S.) Supreme Court has embarked on a program of reshaping constitutional doctrine so as to encourage and facilitate the emergence of a fully developed Market State in this polity, with a view to positioning the United States to be successful in meeting the competitive challenges of a new, post-Cold War international order. … Proponents of this vision of a globalized economy characterize the United States as ‘a giant corporation locked in a fierce competitive struggle with other nations for economic survival,’ so that ‘the central task of the federal government’ is ‘to increase the international competitiveness of the American economy.” (Item in parenthesis above is mine. See the only full paragraph on Page 643 of the Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law paper “Moral Communities or a Market State: The Supreme Court’s Vision of the Police Power in the Age of Globalization” by Antonio F. Perez and Robert J. Delahunty.)

“Major American businesses have made clear that the skills needed in today’s increasingly global marketplace can only be developed through exposure to widely diverse people, cultures, ideas, and viewpoints. What is more, high-ranking retired officers and civilian leaders of the United States military assert that ‘[based on their] decades of experience,’ a ‘highly qualified, racially diverse officer corps … is essential to the military’s ability to fulfill its principle mission to provide national security.’ …” “In short, the Court based its constitutional reasoning on the contention of a group of the Nation’s key corporate, political, and military leaders that the Nation’s prospects of success in the face of international strategic threats, as well as continued stability and perceived legitimacy in its domestic political institutions, required racial preferences in elite formation through our major educational institutions.” (See the Catholic University of America paper I referenced earlier; therein, see Page 699.)

“Liberal democratic societies have, in the past few decades, undergone a series of revolutionary changes in their social and political life, which are not to the taste of all their citizens. For many of those, who might be called social conservatives, Russia has become a more agreeable society, at least in principle, than those they live in. Communist Westerners used to speak of the Soviet Union as the pioneer society of a brighter future for all. Now, the rightwing nationalists of Europe and North America admire Russia and its leader for cleaving to the past.” (See “The American Interest” article “The Reality of Russian Soft Power” by John Lloyd and Daria Litinova.)

“All in all, the 1980s and 1990s (and the 2000s and the 2010s also, Muller’s book is written in 2002) were a Hayekian moment, when his once untimely liberalism came to be seen as timely. The intensification of market competition, internally and within each nation, created a more innovative and dynamic brand of capitalism. That in turn gave rise to a new chorus of laments that, as we have seen, have recurred since the eighteenth century: Community was breaking down; traditional ways of life were being destroyed; identities were thrown into question; solidarity was being undermined; egoism unleashed; wealth made conspicuous amid new inequality; philistinism was triumphant.” (From the book “The Mind and the Market: Capitalism in Western Thought” by Jerry Z. Muller; therein, look to the section on Friedrich Hayek)

“Capitalism is the most successful wealth-creating economic system that the world has ever known; no other system, as the distinguished economist Joseph Schumpeter pointed out, has benefited ‘the common people’ as much. Capitalism, he observed, creates wealth through advancing continuously to every higher levels of productivity and technological sophistication; this process requires that the ‘old’ be destroyed before the ‘new’ can take over. … This process of ‘creative destruction,’ to use Schumpeter’s term, produces many winners but also many losers, at least in the short term, and poses a serious threat to traditional social values, beliefs, and institutions.” (From the book “The Challenge of the Global Capitalism: The World Economy in the 21st Century,” by Robert Gilpin, see the Introduction.)

“In this new world disorder, the power of identity politics can no longer be denied. Western elites believed that in the twenty-first century, cosmopolitanism and globalism would triumph over atavism and tribal loyalties. They failed to understand the deep roots of identity politics in the human psyche and the necessity for those roots to find political expression in both foreign and domestic policy arenas. And they failed to understand that the very forces of economic and social development that cosmopolitanism and globalization fostered would generate turbulence and eventually resistance, as ‘Gemeinschaft’ (community) fought back against the onrushing ‘Gesellschaft’ (market society), in the classic terms sociologists favored a century ago.” (See the Mar-Apr 2017 edition of “Foreign Affairs” and, therein, the article by Walter Russell Mead entitled “The Jacksonian Revolt: American Populism and the Liberal Order.”)

“Thus, affirmative action, understood and applied in this manner, has fundamentally different goals from the Court’s Cold War-era project of desegregation. (Back then) desegregation served the needs of a Nation State that was attempting to be ‘the provider and guarantor of [individual] equality.’ In large part, desegregation was an effort to assimilate minorities into the dominant national group, thus forging a national people that could meet the external Communist enemy with a united front, and so denying that enemy any opportunity to exploit potentially dangerous rifts within the Nation. Affirmative action, as upheld in ‘Grutter,” is also thought to serve the Nation’s strategic needs, but in an international environment that is markedly different from the Cold War. No longer does the Court feel a need to foster a national unity that transcends racial (etc.?) consciousness or to further the assimilation of racial (etc.?) minorities. Such strategic needs have passed, together with the passing of the Cold War’s chief external threat. Thus the ‘Grutter’ Court could view the prospect of multiculturalism (etc.?) with equanimity despite the fact that, as Bobbitt correctly perceived, multiculturalism (etc.?) makes it ‘increasingly difficult’ for a Nation State ‘to get consensus on public-order problems and the maintenance of rule-based legal action.’ Rather than regarding the rise of multiculturalism (etc.?) as a liability that had the potential to weaken or even fracture the Nation, the Court saw it an an asset to be exploited for all the advantages it could bring American business in their international transactions. And again, race (etc.?)-conscious governmental actions is viewed through the prism of its usefulness, not its morality.” (Items in parenthesis above are mine. See Pages 702 – 704 of the the Catholic University of America paper that I referenced initially above. Note that this paper is written in the year 2005.)

Thought and Question — Based on the Above:

From our nations earliest history, such things as “race issues,” indeed, would seem to have often been seen be through an “economics, an “economic competition” and, thus, through a “national security” lens.

Thus, much like yesterday, likewise again today, such things as “race issues” (such as racism and anti-racism and now sex issues, etc., also?) — for these self-same “economics,” “economic competition” and “national security” reasons — “rate” our significant study and understanding now?

We should note that, in the very recent U.S. Supreme Court case of “Students for Fair Admissions, Inc.,” the now more-conservative Supreme Court seems to have effectively (a) overturned the “Grutter” case which was the basis for my second and last quoted items above and, as per America’s business, military and educational leaders, (b) thereby lessened/undermined the ability of America’s businesses and military to compete — as effectively as they otherwise might have been able to do — on the world stage today and going forward. (In both “Grutter,” and in “Students” cases, American business, military and educational leaders seem to have made such an argument.)

Thus, once again, we see “racial issues” — relating to such things as “economics,” “economic competition” and “national security” — being important matters for our military (etc.) students to significantly study and understand today? (Herein, America’s business, military, educational and judicial leaders certainly significantly studying — and significant expounding upon — these such “racially”-related matters?”)

I taught in Beukema’s Dept of Social Sciences (1981-1984).

This piece doesn’t make the case for teaching Wokeness at West Point. Nice try. In Sept 2021 I went through the academic offerings at USMA to identify specific courses and classes that teach CRT. There was enough to be concerned. Furthermore, I’ve read the original source material for CRT (18 books to date). Consequently, I know the content.

The issue in 1930’s Econ was about teaching the policies. Policies are government outputs that become economic outcomes. They aren’t economic theory. The New Deal and Trickle Down (more aptly called A Rising Tide Lifts All Boats) aren’t micro or macro econ.

Conversely, CRT is Cultural Marxism. It is political, economic, and historical theory. Even though giving its gibberish the honorific of “theory” is an unscholarly stretch of imagination. It substitutes racial identity politics in a permanent hierarchy of victimhood for the class warfare of classical Marxism.

If the classes teaching CRT are taught to illustrate the many and manifold errors of CRT, that would be okay. Since we don’t have access to see how they are taught, I’ll wager they are given far more weight than they deserve. They’re probably offered in a favorable light.