[Military Strategy: A General Theory of Power Control] had a major impact on U.S. Navy thinking in the 1980s when the service formulated its maritime strategy.

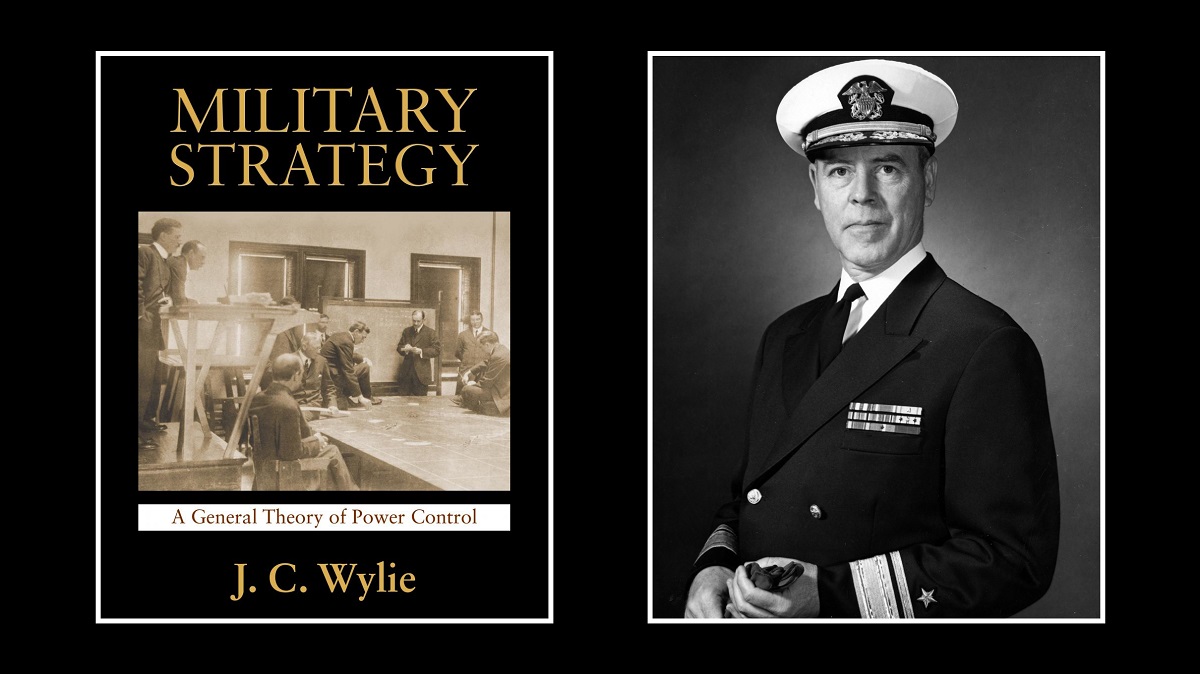

The naval historian John B. Hattendorf observed that “Rear Admiral J. C. Wylie was the first serving officer since Luce and Mahan… to become known for writing about military and naval strategy.” Scholars and practitioners consider Wylie’s 1967 book Military Strategy: A General Theory of Power Control a classic. It had a major impact on U.S. Navy thinking in the 1980s when the service formulated its maritime strategy. Surprisingly, it is not Wylie’s book but an article published years before that remains most relevant as the United States wrestles with its interests in the Indo-Pacific region and China as a strategic competitor.

Wylie (1911-1993) served more than forty years in the U.S. Navy and was a first-rate strategic thinker. Assigned to the Naval War College staff in 1950, he designed a strategy course that likely inspired his first major work, “Reflections on the War in the Pacific,” in the April 1952 issue of the Naval Institute’s Proceedings. It is an appraisal of the U.S. military victory in the Pacific during World War II viewed through four strategic decisions. Revisiting those decisions provides useful insight for today’s U.S. policymakers contemplating a potential conflict with China.

Wylie stated that the first strategic decision was how the Japanese interpreted the November 26, 1941 diplomatic note that the U.S. Secretary of State gave the Japanese ambassador to the United States. Essentially, the note’s wording forced Japan to either withdraw from China or go to war to protect its interests. The United States, Wylie contended, failed “to appreciate a situation as it may appear to a government other than our own.” More recently, scholar Takeo Iguchi notes that withdrawal from China would have undermined Japan’s control of Manchuria, Korea, and Taiwan, which were all vital to its interests. Adding to the probability of misinterpretation was Japan’s own problematic foreign policy of 1940 and 1941, which Iguchi characterizes as “inconsistent, unsteady, and a bit haphazard.”

The attack at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, was a result of the next strategic decision: the problem of how to start a war. Wylie noted the Japanese were in a situation not unlike that of England in 1755 as described by Sir Julian Corbett: “The principle of securing or improving your strategical position by a sudden and secret blow before declaration of war is, and was then, well known. Almost every maritime war which [England] had waged had begun this way.” The United States, Wylie contended, failed “to be aware of the normal, routine historical precedents in just such a situation as this one.”

The third strategic decision Wylie discussed was “the decision on how to fight the war,” which he called “the basic strategy of war.” He compared the Japanese and U.S. strategies. Japan realized that beyond China, it “must control southeastern Asia and the Indonesian island groups” for their natural resources. It planned for a war “limited in its scope to the seizure, control, and exploitation of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.” By early 1942, it had achieved its initial objectives, and, at the height of its military expansion, then had the of controlling and holding its gains. In other words, Japan wanted a war of limited geographic objectives, but it did not have “a control sufficient to limit [the war].”

The United States, using its sea power, turned the conflict “into something approaching an unlimited war.” This asymmetry in how the war was fought was a major factor in its outcome. Japan attempted to fight a limited war encompassing its geographic interests, while the United States fought not only to recapture the conquered areas but also to eliminate Japanese power in Asia by securing an unconditional surrender. Wylie contended that limited war was a “treacherous experiment to embark upon as it requires the participants to have, in reserve, the relative strength to fight an unlimited war.” Japan lacked the strength to keep the war within “pre-selected bounds” and ultimately, it led to defeat.

Wylie also maintained that Japan’s failure to think in global terms was a strategic mistake. If it had been able to control the Indian Ocean in the spring of 1942 rather than limiting itself to a single raid, it would have been disastrous for the Allies; Japanese control might have been decisive since most of the supplies going to the British in North Africa to fight Rommel and to the Soviet Union came around the Cape of Good Hope up through the Red Sea or to the Persian Gulf. The United States would have had to pull more of its resources from the Pacific to fight the war in the Atlantic and in Europe, thereby allowing the Japanese to consolidate their strategic perimeter. In that instance, the “effect of sea power would make itself felt in a chain reaction around the world,” all to Japan’s advantage.

Despite changing contexts and technology, Wylie’s article provides enduring cautionary insight for thinking about U.S. naval strategy in the Indo-Pacific.

Finally, Wylie examined the fourth strategic decision: the two ways the United States employed force to achieve its policy objective regarding Japan. His analysis on this point provided what might be Wylie’s most famous contribution to strategic theory, the idea of sequential and cumulative strategies. The first element was the two great advances across the Pacific to Asia’s coast and the shores of Japan: the island-hopping campaigns of General Douglas MacArthur’s Southwest Pacific campaign and Admiral Chester Nimitz’s Central Pacific advance. In Wylie’s words, these were “sequential strategies, a series of discrete steps or actions, with each one of the series of actions growing naturally out of, and dependent upon, the one which preceded it.” The second way the United States defeated Japan was through its cumulative strategy of submarine warfare against Japanese merchant shipping. This “collection of lesser actions” was not sequentially interdependent but eventually sunk 55% of the Japanese tonnage, resulting in Japan’s near “economic strangulation.” The two strategies occurred simultaneously but independently. The result was that Japan had “to give in” or “approach national suicide.” Wylie concludes that U.S. “strategic success in the future may be measured by the skill” in balancing sequential and cumulative approaches to the “most effective and least costly attainment of our goals.”

Despite changing contexts and technology, Wylie’s article provides enduring cautionary insight for thinking about U.S. naval strategy in the Indo-Pacific. The first strategic decision speaks to the issue of perception and misperception, that is a state’s political leaders can misunderstand how their signals to another state will be interpreted, or miscalculate the costs of certain actions, or misjudge military capability. While renowned political scientist Joseph Nye remains optimistic about U.S.-China relations, he warns that both sides should be wary of the possibility of miscalculation. “After all, more often than not, the greatest risk we face is our own capacity for error.” Nye underscores that miscalculation could occur not only because of U.S. and Chinese nationalistic fervor, but also given “the clumsiness of China’s diplomacy and the longer history of standoffs and incidents over Taiwan, the prospects for an inadvertent escalation should worry us all.” Detailed understanding of another country’s diplomatic practices and its ambassadors as its agents is crucial as is strategic empathy so as not to result in unintended and unwanted consequences.

As to the second strategic decision, a great power war in the Indo-Pacific initiated by a surprise attack is plausible as a senior Japanese defense official verbalized two years ago. Moreover, a surprise attack is linked to miscalculation. Lesley Kucharski, an analyst at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, has pointed out that the United States in 1941 based its calculation of Japanese intentions on “mirror imaging deterrence and threat perceptions,” factors that remain pertinent in today’s security environment. She urges the United States to “prepare for surprise contingencies, even if it views them as escalatory and mutually undesirable.” This is a prudent step as China has a “doctrinal preference for surprise and first attack,” similar to Imperial Japan.

With respect to the third strategic decision, China is better prepared than Imperial Japan to improve the odds of ensuring a war remains limited. Like Imperial Japan, China seems to prefer a geographically limited war with its near seas defense strategy of the first and second island chains; an anti-access, area denial strategy; as well as several other components. However, China, unlike Imperial Japan, is better postured both to withstand unlimited war and, importantly, to reduce its likelihood. First, China has taken steps to reduce its economic vulnerabilities. Its “string of pearls” helps safeguard its sea lines of communication, while its Belt and Road Initiative provides an overland supplement to its sea trade that simultaneously creates additional economic incentives for its Belt-and-Road partners to at least remain neutral in any future conflict. Second, China also has greater military power than Imperial Japan did to encourage its opponents to fight a limited war. It is building a global navy, with particular attention to projecting power into the Indian Ocean. Unlike Imperial Japan, China has a permanent presence there. Furthermore, a global navy provides China with the option of horizontal escalation through the opening up of new theaters of operation beyond the western Pacific to achieve victory. Finally, China has nuclear weapons and has taken recent action to expand its arsenal. This may encourage restraint, but as a recent simulation suggests, the Chinese may have greater confidence that they can manipulate the threat of nuclear weapons to control escalation. Although China has a “no first use” nuclear weapons policy, it may be “willing to brandish nuclear weapons or conduct a limited demonstration of its nuclear capability” under certain circumstances, such as to deter or end U.S. involvement in a conflict over Taiwan. U.S. officials would undoubtedly view a limited demonstration as a major escalation.

Lastly, sequential and cumulative strategies as a solution remain pertinent in U.S. Navy fleet warfare doctrine, and getting the balance right will likely be important. Even with the Belt and Road Initiative, China still has a reliance on imported petroleum and liquid natural gas, much of which must flow through the Strait of Malacca, a strategic checkpoint. This dependence gives the United States the opportunity to use a cumulative strategy in the Indian Ocean against China. Yet this might be catastrophic success for the United States, if doing so imperiled China’s economic survival leading to vertical escalation of the conflict. Nonetheless, the success of a U.S. Navy sequential strategy may hinge on whether the United States decides to make its strategic investments in developing technological superiority or in substantially growing the fleet. The urgency of the latter argument is getting congressional attention to redress the imbalance in force structure but is also prompting reinvigoration of the Air/Sea Battle operational concept. Today’s battlespace is decidedly different than that of World War II. Nevertheless, Wylie and one of his contemporaries, Vice Admiral Richard L. Conolly, argued that military history offers a particular type of knowledge: “how to think more clearly in order to properly analyze the situations and assess and evaluate the various factors that produce success or failure, victory or defeat.” This is knowledge that strategists and warfighters still need to meet the strategic and operational challenges of war. As Toshi Yoshihara, an expert on the Chinese naval strategy, has observed, “the Sino-U.S. rivalry is as much an intellectual contest as it is a material competition.”

Frank Jones is a Distinguished Fellow of the U.S. Army War College where he taught in the Department of National Security and Strategy. Previously, he had retired from the Office of the Secretary of Defense as a senior executive. He is the author or editor of three books and numerous articles on U.S. national security.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

Photo Description: Rear Admiral Joseph Caldwell Wylie, Jr., American strategic theorist and author.

Photo Credit: Photographer unknown, Courtesy U.S. Naval Institute