Just as a chess master with a positional advantage is willing to trade queens with his opponent, an adversary prepared to operate in a degraded electronic environment may be willing to do the same.

The U.S. military’s technological advantage may also be its biggest weakness, as its reliance on technology has left it under-trained and unprepared in fundamental aspects of warfighting. Technology is important, but it cannot be assumed to be decisive. History offers too many examples of militaries that were surprised by a technological mismatch. Indeed, the cyber capabilities of some U.S. rivals are formidable and growing, and may be a decisive factor, even in the tactical fight. An adversary who exceeds or simply circumvents key U.S. military technology will have the edge if U.S. forces are unable to match that opponent’s tactical or operational creativity and competence. Just as a chess master with a positional advantage is willing to trade queens with his opponent, an adversary prepared to operate in a degraded electronic environment may be willing to do the same.

Certainly, an opponent facing the overwhelming technological advantage of the U.S. military may consider this approach. However, the U.S. may find itself in a position where the electronic advantage lies with its adversary. In such a case, is trading queens a strategy that the U.S. is prepared to use, or is even capable of employing effectively?

As the Stryker Brigade Combat Team maneuvered north towards its objectives, crews at a temporary airbase fueled and armed a fighter wing of F-35As in preparation for supporting attacks. Offshore, a carrier group, having bypassed a storm system which unexpectedly formed along its route, was still out of range. It was expected within a couple of days.

Given the urgency of the mission, the Stryker team was ordered to take up offensive positions well before the division and its supporting forces had arrived. This meant that the extent of ground operations was limited to what the team arrived with. Robust as that formation was, there were limits to what you could bring on a rapid deployment.

As the lead reconnaissance vehicles approached their positions, the enemy revealed itself to the Stryker’s sophisticated sensors. Less than a battalion of T-72 tanks and a few, much older tanks sat arrayed in a sloppy defensive posture, seemingly oblivious to the scouts’ presence or to the maneuvers of the rest of the team. The enemy’s location and status were quickly updated on the Common Operational Picture — a shareable computerized display of the battlefield — and were transmitted to the Joint Force. This looked to be a straightforward attack on a static position, using overwhelming force. Overmatch!

Air support should have been up already, but there was some sort of delay. No matter. With the local overmatch, the ground forces would be sufficient to destroy the threat on this objective. Surprise was a fleeting condition and taking advantage of it now would be worth the risk. The team commander began his attack with a concentrated artillery fire, forcing the enemy to button up, as friendly infantry and armor forces maneuvered into their attack positions.

When the artillery began falling, however, the lead scouts reported that the impact of the barrage was off target. Attributing this to human error, the scouts again sent in the correct grid for the enemy’s command and control elements. Again, the artillery was off target, only this time, it was short… uncomfortably short. What the heck was going on?

The maneuver units were almost in place, ready to advance, but the objective was not “shaped” the way the commander wanted. Joint fires had not arrived (where was the Air Force?) and the artillery was ineffective. One battalion reported that it couldn’t see its adjacent unit on the ground, although it appeared to be in position on the computer screen.

By now, the element of surprise had slipped away and they were faced with a potentially fair fight. Well, almost fair. The brigade combat team was equipped with the latest technology, including the new 30mm cannon that could cut through the enemy’s armor.

The commanding officer ordered the attack to proceed, committing his ground troops while shouting obscenities at his artillery commander over the net, for the ineffective artillery demonstration. The battery commander insisted that he’d fired the correct grid and had no explanation for why the rounds weren’t landing on enemy formations.

As the lead vehicles lurched forward towards their final assault, the enemy’s vehicles began to move. The commander had anticipated this: the enemy force would withdraw as soon as it realized it was facing a U.S. Stryker brigade combat team. But the vehicles weren’t withdrawing. They were maneuvering. They were actually moving forward, into positions where they could close with the U.S. team, and bring superior firepower against the lightly-armored Strykers.

The emphasis on technology at the expense of basic skills, weapons, and tools that don’t depend on vulnerable electronic systems has weakened the U.S. military’s ability to operate in low-tech environments.

A bright light suddenly flashed overhead; a non-nuclear electromagnetic pulse (EMP), designed to destroy all electronics within a few hundred kilometers. Surely the Stryker, with its “hardened” systems, was immune to such things (?). And why would the enemy use one now, with his own forces so close by?

The electronic pulse was not powerful enough to destroy the electronics in the hardened combat vehicles, but its effect on the rest was immediate: some vehicles stopped, some stalled. Others seemed to weather the pulse without issue. The communications, positioning, and targeting systems were all hit, some with severe damage. The operational upset would require most electronic components to restart, while others would need minor repair before they could operate.

This was a most inconvenient time to reboot. The enemy’s tanks were still maneuvering and time was short. But how could their tanks still be moving? Surely an EMP strong enough to disable so many platforms in the area would affect all: friend or foe. It was at this moment that the troop commander in the lead Stryker realized that the expected attach was not coming from the idle T-72s. Instead, the much older T-55s that were moving. With horror, he watched as the 1958 vintage tanks slowly swung their main guns towards his position, as his driver frantically tried to restart the vehicle and its onboard computer.

The subsequent battle went poorly for the technology-bound U.S. forces. Computer systems governing the arming and fueling of the Air Force fighters had been compromised, either by a virus or by hackers. The succeeding delays meant the ground forces were left to their own devices. The GPS-spoofing attack made artillery systems and navigation unreliable at best. The EMP’s effects were temporary, but the timing was such that the force which prepared to fight without electronic assistance had a distinct advantage. U.S. forces, completely reliant on the technology they’d invested so much in, lacked the training and equipment necessary to operate in an exclusively low-tech environment. It was the largest defeat of a U.S. Army ground unit in decades.

Twenty-first Century warfare will undoubtedly reward combatants who employ the most innovative approaches. Militaries such as the U.S.’s that continue to invest heavily in high-tech solutions to battlefield challenges will lead the way in technology development and will continue to become increasingly reliant on it. Yet, the vulnerability of these systems is only part of the problem: the emphasis on technology at the expense of basic skills, weapons, and tools that don’t depend on vulnerable electronic systems has weakened the U.S. military’s ability to operate in low-tech environments.

U.S. forces largely cannot move, shoot, or communicate without satellite-enabled technology. An adversary who figures out how to neutralize those systems, even briefly, and who is prepared to operate without high-tech tools, will have an insurmountable advantage. This advantage may be temporary, but a temporary advantage at the right moment can be decisive.

For over six decades, the U.S. military has succeeded in battle because it has set the battlefield context to preserve key tactical and operational advantages. It would be folly to assume that this condition will continue indefinitely. Unless the U.S. invests in regaining the ability to fight in the low-tech domain, it will cede the initiative to rivals who are willing and able to exploit the environment to suit their advantages.

Robert Dixon is a Colonel in the U.S. Army and a member of the U.S. Army War College class of 2015. The views expressed here are the author’s, and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the U.S. Army or the U.S. Government.

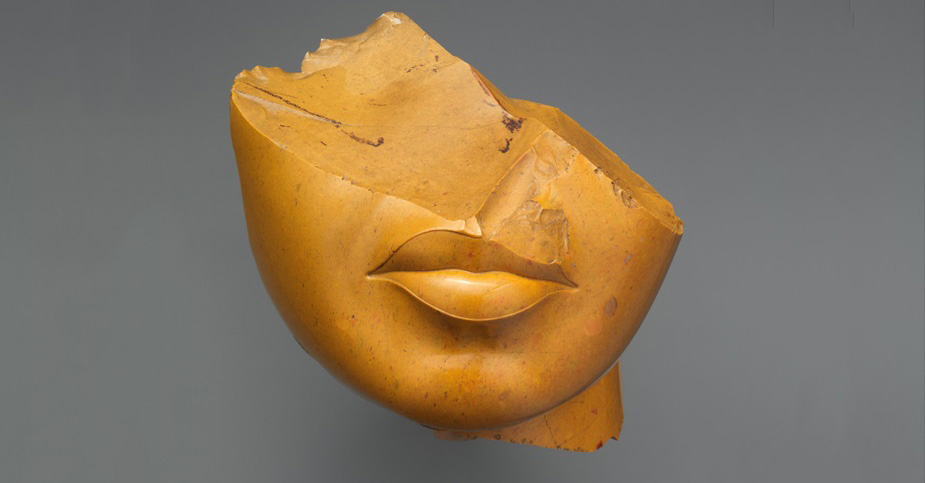

Photo credit: Harkness Gift/Collections/Metropolitan Museum of Art