General Bradley learned and honed his leadership skill by watching superior officers – good and bad — for traits to emulate or avoid.

General Omar Bradley wrote, “no commander can become a strategist until he first knows his men. Far from being a handicap to command, compassion is the measure of it. For unless one values the lives of his soldiers and is tormented by their ordeals, he is unfit for command.” General Bradley’s unique leadership traits and style revolutionized leadership theory and remain worthy of emulation in the ranks. Unlike a number of his counterparts, who were colorful and employed an autocratic leadership style, Bradley was an unassuming leader who was polite, courteous, and collaborative. He was popular with subordinates and peers alike, for not only his human understanding and consideration of their needs, but also his humility. For example, he invited his peers’ criticism to refine military plans for success. He recruited younger talent, to bring fresh thinking to stubborn problems and embodied the ‘servant leadership model long before academic journals described it. General Bradley learned and honed his leadership skill by watching superior officers – good and bad — for traits to emulate or avoid. His legacy endures as that of a pioneer, who transformed how the military and business worlds view leadership.

While teaching mathematics at West Point and serving as an Infantry School instructor, Bradley displayed nascent servant leadership qualities. Then Lieutenant Colonel George Marshall spotted them, as Bradley’s superior at the Infantry School. He wrote this of Bradley: “quiet, unassuming, capable, [with] sound, common sense. Absolute dependability, give him a job and forget it.”

Bradley elicited his students’ best characteristics and taught them problem-solving skills, as well as infantry tactics, techniques, and procedures, as he led their growth as both individuals and military professionals. As Bradley advanced through the ranks, he understood the importance of listening, empathizing, and meeting his men’s and his superiors’ needs.

During his time in the War Department, Bradley worked for General George Marshall’s General Staff. Marshall devoted energy to mentor Bradley and the other young officers under his command. He cultivated an environment which encouraged people to take unorthodox approaches to solve problems. Marshall also assigned tasks and left his personnel alone to complete their work, which afforded them the opportunity to think “outside the box” and make independent decisions. Bradley commented on this culture and Marshall’s leadership by stating, “I was inspired to do my utmost.” Bradley’s main occupation was to summarize and report on various papers of interest to the Army. After a week of getting such summaries, it troubled Marshall that no one had disagreed with any of the papers’ recommendations or offered any contradicting viewpoints for him to consider. Soon after, Bradley disagreed with a course of action Marshall himself had decided. Marshall responded, “Now that is what I want. Unless I hear all the arguments against an action, I am not sure whether I am right or not.” Bradley grasped what Marshall needed and fulfilled his demand for critical analysis. This demonstrated Bradley’s empathetic listening skill, courage, and good stewardship of staff outputs that could offer Marshall the well-rounded viewpoints he sought.

Bradley took what he learned from Marshall to evolve key aspects of his servant leadership, such as: growing his people, building a community within each of his commands, and exercising foresight. One of his primary goals was to unleash his team’s talent to solve problems. Bradley often let subordinates brief plans for major actions, interjecting only if they got the enemy’s disposition or strength wrong. He avoided embarrassing them, because he knew if he focused on their weaknesses, they would lose confidence and become less useful to the war effort. He was humble when receiving accolades and passed praise onto his men, to build their self-confidence in their abilities. He established a community of openness, which encouraged staffers to respectfully disagree with him or other superiors, if they thought them wrong on some point. To Bradley, staff officers who always agreed with their superiors were of limited value.

On the battlefield, Bradley’s holistic grasp of the conflict plane helped him identify risks and opportunities to inform calculated, objective decisions. He knew his enemy, each side’s available resources, and his own men’s limits. Such leadership contributed to many of Bradley’s triumphs. He had an uncanny ability to hold all the variables of an impending battle in his head, such as his artillery’s strength, the Allied close air support he could expect, his divisions’ fighting capability, and his commanders’ leadership aptitudes. He could also conceptualize an opposing force’s ability to fight, along with its battlefield disposition. He once politely interrupted a colonel under his command’s briefing to correct him, saying, “No, Colonel, the panzer grenadier outfit is there. The panzer division is on its flank. Sorry to interrupt.”

Above all, Bradley thought critically in stressful situations, even after setbacks. After the Allies’ successful Normandy landings, his forces suffered disaster in their first attempted breakout from the beachhead. He examined the operation’s minute details, to discover why his plan failed. This revealed he had biased his calculations of German movements and attack formations using data from previous engagements with the Wehrmacht. He quickly fixed his mistakes and reengaged, to lead a brilliant campaign from Normandy’s beaches to Germany’s Elbe River. Such tenacity and resilience despite failure reinforced his leadership excellence.

What Bradley learned through formal education and by observation, he synthesized and executed in the crucible of war.

In time, Bradley defeated a technologically superior enemy, not only with critical thinking, adaptability to change, and sound calculation, but also with historical mindedness about past leaders’ successes and failures, which he could apply to his present contexts.

What Bradley learned through formal education and by observation, he synthesized and executed in the crucible of war. His time at West Point influenced how he viewed leadership. There, he studied military history and learned lessons about fighting, generalship, innovation, and past leaders’ mistakes. Such lessons enabled him to understand what made for great or poor leadership.

The people Bradley served had a profound influence on the leader he became. He emulated Marshall, saying, “From General Marshall I learned the rudiments of effective command. When an officer performed as I expected him to, I gave him a free hand. When he hesitated, I tried to help him. And when he failed, I relieved him.”

Bradley knew that he could not be an expert in every aspect of his units’ daily workings. However, by visiting his men and showing interest in what they were doing, he kindled their morale. Such visits also permitted him to assess his commands’ combat capabilities and to conceive of new ways to employ them. To tap into fresh, creative thinking about planning and combat innovations, he recruited younger talent onto his staffs. He gave them broad orders and empowered them to figure out the execution details, letting them succeed or fail on their own merits. Such delegation let him focus on his men’s wellbeing and on assessing the German military’s capacity and intent.

While many of his peers fed cults of personality to swell their self-images, Bradley saw his role as a facilitator to empower his men to accomplish great feats. His subtle leadership during his time as the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff proved more effective than more directive styles and enabled the U.S. military’s development into a more cooperative institution. The environment he created was one where critical thinking was encouraged, flat leadership organizations abounded, and the free flow of information up and down the chain of command was the norm.

Bradley fundamentally changed how both the U.S. military and business communities would eventually define leadership. Leadership theorists point to Bradley’s collegial, accommodating style as an example other leaders should follow. His mild-mannered nature and collaborative approach were an anomaly amongst his contemporaries, who often led as autocrats in isolation from each other. History had revered the ‘General MacArthurs’ and the ‘Admiral Nimitzes’ of World War II well into the 1960s — until leadership theorists showed how such leaders’ egos actually inhibited teamwork. Their inability to collaborate had damaged the war effort at times and this tarnished their reputations as exemplary leaders. Bradley’s leadership traits were unique during World War II. His men called him the “GI General,” who put his men’s welfare and the Constitution’s ideas before himself. He embodied servant leadership long before its time and refined his attributes during the struggles of war. He exercised critical thinking in crucial moments during World War II, to defeat a ferocious enemy war machine.

Throughout, General Bradley sought to develop his men’s own leadership abilities, knowing they would be tomorrow’s commanders. His style represented a fundamental shift in the way contemporary American society views successful leadership. Today’s military leaders can learn much from his subtle demeanor and leadership approach, attributes that cultivate environments in which people can grow and flourish.

Todd Moulton is a Lieutenant Commander in the U.S. Navy and an intelligence planner at U.S. Second Fleet. He is also an Information Warfare (IW) Warfare Tactics Instructor (WTI). He is a graduate of the Air University, National Intelligence University, Seton Hall University, and University of Michigan.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, the U.S. Navy or the Department of Defense.

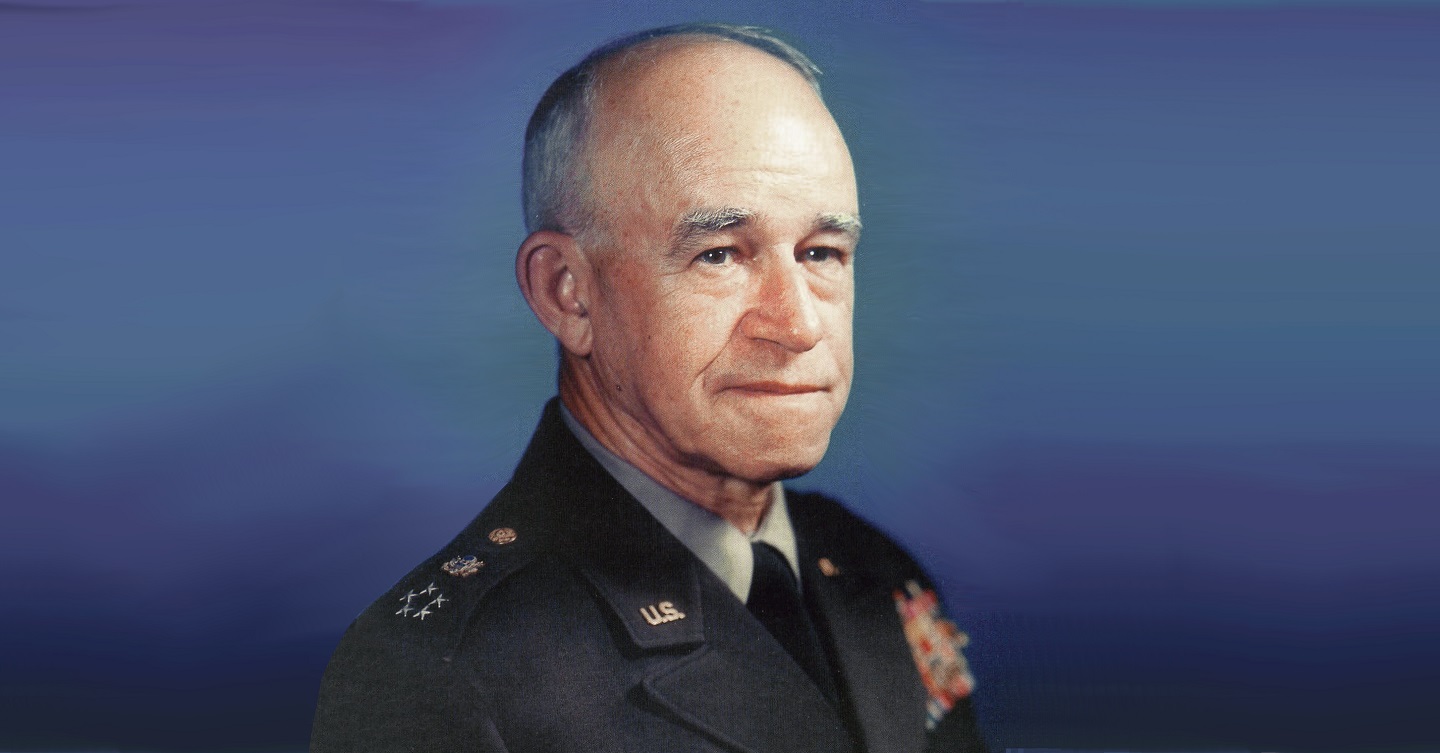

Photo Description: U.S. General of the Army Omar Bradley, 1st Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

Photo Credit: U.S. Army Photo

Thanks.