The reader will encounter social comment and contemporary (at the time of writing) ethical discussion as the author steps in a loose chronological order through the campaign.

The food critic Jay Rayner achieved global notoriety with a brilliant scathing review of a Paris restaurant. When asked what the critical skill in his profession was, he responded, ‘learn to write.’ Good penmanship leads to the creation of far superior and more engaging chronicles. George MacDonald Fraser, a master of prose, provides a personal history in the late stages of the often-neglected Burma campaign of World War II, in Quartered Safe Out Here. He was the author of the popular Flashman series of novels and the scriptwriter for numerous successful films, including a Bond movie. MacDonald Fraser provides an exceedingly well-written narrative.

The reader will encounter social comment and contemporary (at the time of writing) ethical discussion as the author steps in a loose chronological order through the campaign. This approach does not make it difficult to follow; indeed, it makes for a more enjoyable journey. The author does not get bogged down in the sustained hardship and fear these soldiers experienced, but at the same time does not make light of it and constantly keeps aware of the demands of combat in the tropics.

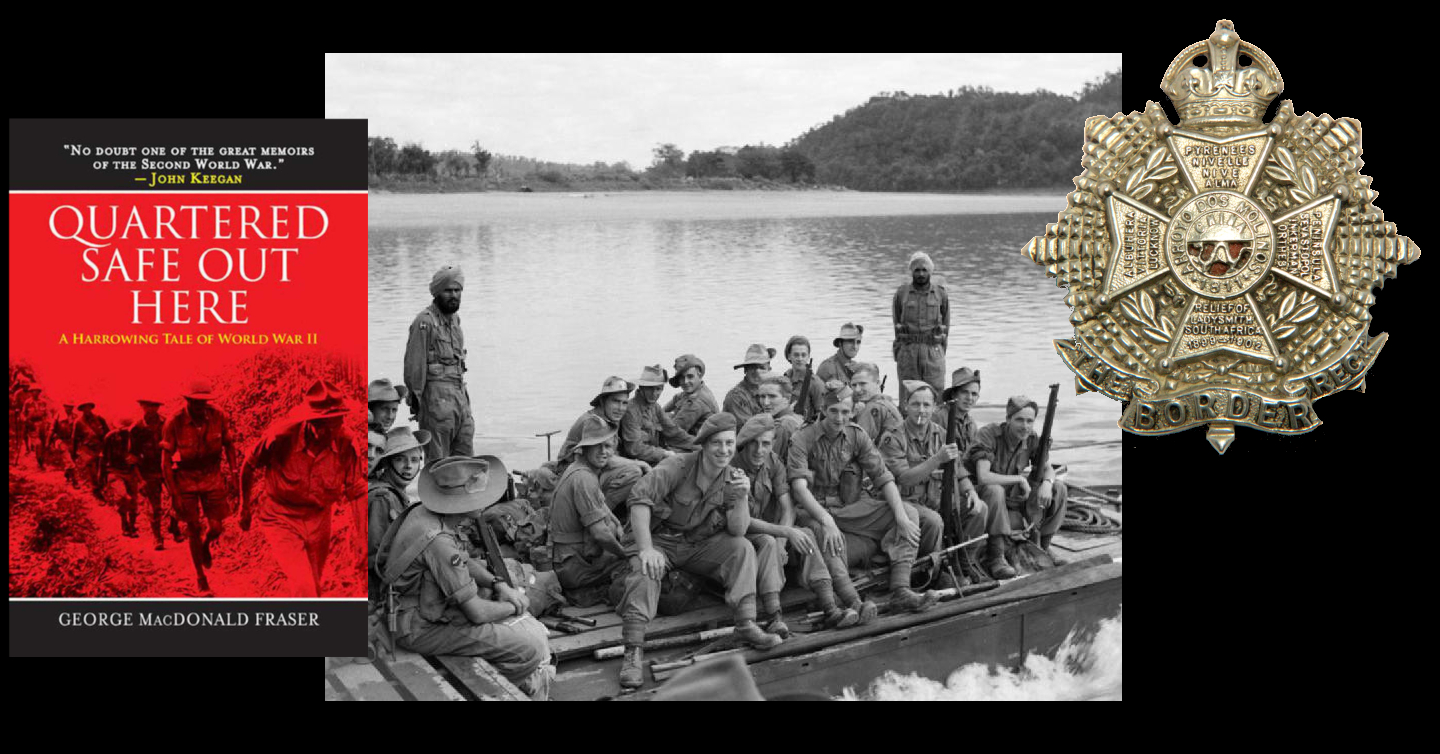

MacDonald Fraser served as an infantryman in The Border Regiment. Two battalions of this regiment fought in the Burma Campaign, each one allocated to an Indian Division. Both battalions fought in the most significant battles of that campaign, from the Siege of Imphal to the final eviction of Japanese forces from Burma. However, MacDonald Fraser’s perspective is generally kept even tighter than his battalion, primarily focussing on the most vital element of this combat arm, the infantry section (“Nine Section”). For those interested in combat motivation in sustained, arduous conditions, this provides reason enough alone to read this book, aside from its literary merits.

MacDonald Fraser reinforces the importance of this style of history in his introduction; official histories fail to carry the visceral nature of war. He states, “eleven hundred Japanese died in that battle; the official history records the fact but doesn’t tell you how.” (xii)

He also challenges broad-brush assessments of the campaign both during and after; by citing two highly personal experiences. The first was a naked Japanese officer charging at him armed with only a sharpened bamboo spear late in August 1945, when HQ intelligence assessments said enemy morale was low. His second correction was of an assertion in a later academic essay that the Projector Infantry Anti-Tank (PIAT) weapon was not used in Burma. He contends, ‘Well I carried the bloody thing, and fired it five times, with startling results.’ (xx) Moreover, he describes the mission in great detail later in the text. A riverine ambush of a Japanese supply boat; a task that a conventional light battalion may not be assigned these days (though they probably should?). These examples of clarifying the historical record further reinforce the importance of this type of personal work, particularly when so well written and easy to read.

It is important to note that MacDonald Fraser was meticulous in research for all his writing. He made the equivalent effort in preparing this memoir, including checking the manuscript with his former Commanding Officer. As a result, the bibliography is extensive; this gives the text far greater substance to what is already an astute observation of jungle warfare.

MacDonald Fraser provides insight into a highly proficient infantry unit based on citizen-soldiers. This proficiency is demonstrated when the replacement Corporal for his respected Section Commander, killed in action, is equally skilled (though less colourful). The loss of their Corporal was a point of anger and frustration for the squad, but grieving would have to wait. There are tragically many such instances in the book. All the people encountered in the text are competently focused on the tasks at hand. Sustained combat, it seems, is no place for distraction.

Some readers may find the literal transcription of the Cumberland accents of the soldiers a little challenging to navigate. Still, the author provides more than enough guidance. Of course, despite his incredible candour and perception, he is a man of his era. His attitudes towards the treatment of combat stress are archaic. For a writer who is regarded as meticulous, not looking at what happened to the battalion members after the war is a strange omission. Indeed, while the reasons for writing the book are given, one cannot help, when looking at the tone and style, that this was perhaps therapeutic for him–to finally expunge the horror he experienced. It leads to a straightforward form of prose coupled with a soldier’s unique eye and makes a richer experience for the reader but may at times be confronting. It is a candid recollection of the emotions and experiences of a young man fighting in a far-flung corner of the world.

Although MacDonald Fraser saw and committed acts of extreme violence, and he and his section had ample opportunity to take this application of violence beyond the rules of war, they did not.

Nine Section fought for sustained periods under arduous conditions in a theatre that received little public recognition and fewer resources than others. Death led to a temporary burial in an abandoned slit trench and a quick prayer. Although MacDonald Fraser saw and committed acts of extreme violence, and he and his section had ample opportunity to take this application of violence beyond the rules of war, they did not. It is a well-led unit at all levels with a strong awareness of each other’s strengths and weaknesses. Military readers will take many such lessons from this book.

At the end of the book, the author takes on an issue that was a raging debate when first published (1993), discussing the morality of dropping the atomic bomb on Japan to force an unconditional surrender. The author’s commendable ethical dissection of this issue is deeply personal and worthy of review by all military and strategic theorists. He ultimately concedes that if his section was asked to push on and fight down the Malayan peninsula to eject Japanese forces instead of dropping the bomb, they would have cursed, picked up their equipment, and started marching. At the end of a most brutal global conflagration, duty and the protection of humanity still mattered to these most hardened combat soldiers.

The Border Regiment battalions serving in Burma were likely as capable, if not more so than any contemporary light infantry unit, yet not once in the text are there references to the term ‘warrior’ or even ‘veteran’. It isn’t easy to see how such tropes would have either further inspired them or changed their view. Indeed, they would have likely been met with derision by the characters that MacDonald Fraser describes (including himself). Instead, there is abject acceptance of the horrors of war, the need to endure and do your duty. In the epilogue, MacDonald Fraser is genuinely and rightfully proud of his comrades’ and battalion’s achievements.

I read Quartered Safe Out Here many years ago at the mid-point of my military career; it has remained a ‘within arm’s length’ book ever since– not just because of its immense military value but for its excellent writing and precise critical thinking. World War II threw many talented writers into the jaws of war, such as Norman Mailer and James Jones. MacDonald Fraser writes with equivalent skill. So, it seems, given the current debates around the nature of military service in standing professional armies, to read a well-researched and brilliantly told personal history by a true citizen-soldier will provide an important alternative perspective. It is a memoir that does not inevitably go to places such as God is Not Here, or as some senior leaders biographies read, ‘How well things were going when I was there.’ Instead, it provides a vital soldier’s perspective on a campaign whose narrative is dominated by Field Marshal Slim’s excellent Defeat into Victory of what is often considered a historically neglected campaign.

While the character of war may change, its nature is constant. Quartered Safe Out Here offers a valuable perspective on that nature. It provides insight into what it takes an individual to survive, both (with luck) physically and, more importantly, ethically. A competent and, dare I say it, resilient individual forms the foundation of a high level of unit proficiency in sained combat. The reader gets a rare insight into a world that rarely involves more than a handful of individuals. This is somewhat contrary to current conventional views on creating such unit cohesion—it is a capability built on the sound personal moral compass of the individual with not a warrior ethos or commander’s coin in sight.

I strongly recommend that Quartered Safe Out Here is taken off the dusty shelf and read. Books of this quality and subject are important, valuable, and timeless.

Author’s Note: In researching this book, I came across another recent review from a serving Australian Army Officer, Benjamin Grey, which, while I have not read (for obvious reasons); I thought it would be prudent to acknowledge its existence and provide you with a second opinion.

Jason Thomas is a retired Australian Army Armour officer interested in leadership, strategy and risk. He is living in Dubai and is currently studying for a PhD in aspects of mission command.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

Photo Description: Men of the Border Regiment on a ferry ready to cross the Chindwin River, between Kalewa and Shwegying, Burma, January 1945. (R) Cap badge of the British Border Regiment.

Photo Credit: This image was created and released by the Imperial War Museum on the IWM Non Commercial Licence. (R)Ch bristol via Wikimedia Commons