The impetus for Scotland to rejoin the EU was used as a rallying cry for the pro-independence movement.

In September of 2014, what was to be a once in a lifetime referendum on Scottish independence ended with Scotland choosing to remain in the United Kingdom. Less than two years later, Scots and Britons writ large were asked to take a different decision, this one on continued UK membership in the EU. Scots again voted for union, with 62% casting their votes to remain in the EU. Britons overall, however, made a different decision, narrowly voting to extract the United Kingdom, and Scotland with it, from the EU. This rift over EU membership exposed the persisting desire by many for Scottish independence. As Scottish nationalists consider their next move, the stirring words of Mel Gibson, as William Wallace, in the movie Braveheart linger in people’s minds, “They will never take our freedom.”

The impetus for Scotland to rejoin the EU was used as a rallying cry for the pro-independence movement. Whereas Brexit was principally focused on the United Kingdom’s separation from the European Union (EU), the impact of this action may have more far-reaching unintended effects on other interconnected alliances, partnerships, and unions. This paper will briefly examine one of those consequences, namely, if Scotland were to seek independence in an attempt to reunite with the EU and what this could mean for NATO. Not only would Scotland have to rejoin the alliance, but—among other issues —as a separate sovereign nation, NATO’s nuclear submarine fleet Trident program, currently residing on the Clyde River in Scotland, would be significantly affected. Additionally, geopolitical vulnerabilities which are of serious concern to NATO would dramatically be exposed and possibly increase.

Since the UK’s exit from the EU, the Scottish National Party (SNP) has been actively seeking a second national referendum on independence. The first referendum held on September 18, 2014, saw 55.3% of eligible voters cast ballots against independence. Recent polls, however, show that not much has changed. If another referendum were held today, the numbers would be similar, resulting in Scotland remaining in the United Kingdom. Other polls indicate that public opinion, though, is unpredictable and perhaps even open to manipulation. Scotland’s First Minister Nicola Sturgeon, head of the SNP, hopes that the time is ripe. Although not taking a dominant majority in recent Scottish parliamentary elections, the SNP did get many seats and may unite with the Scottish Greens, another increasingly pro-independence party. First Minister Sturgeon declared after the recent elections that the second referendum is “A matter of when not if.”

A Scottish split with the UK would be unprecedented in NATO’s history, and one that Alliance should watch carefully. A current territory of an existing NATO member would become an independent sovereign nation. This newly independent nation would not automatically become a NATO member and would need to petition for entry as a new member-state. Admission for new members into NATO is not extraordinary but is not accomplished quickly. The procedure is generally lengthy and can take years. The newest NATO member, North Macedonia, began its Membership Action Plan in 1999 and formally joined March 27, 2020. The UK’s former Ambassador to NATO, Mariot Leslie, however, is confident that in the case of Scotland “it would be really quite a fast process.” Would Scotland’s case have priority over other potential candidates, and what effect would this have on other separatist efforts within the Alliance’s territory.

Despite, the SNP having called for a nuclear-free Scotland for years, Scotland has been a part of the United Kingdom. Therefore, London, not Edinburgh, called the shots and based the British nuclear force in Faslane, Scotland. Unlike the United States, the UK only has Trident submarine-launched nuclear capabilities. The SNP and the Scottish Labour Party are staunchly anti-nuclear and have previously called for the Trident program to be canceled. In the 2020 submission to the UK Integrated Defense Review, the SNP stressed the high cost of the Trident system and advocated that the money be spent on other conventional weapons or invested in healthcare, childcare, and education. This means if the SNP were to remain in power in an independent Scotland, they would most likely pursue anti-nuclear policies.

An independent Scotland might refuse nuclear weapons on its shores altogether, which could change the defense posture of the British Isles, therefore NATO as a whole. Retired Rear Admiral John Gower, who was previously responsible for the UK’s nuclear program, suggested a shortlist of potential new sites for the submarine fleet. This list included one in the United States, but any choice would come with its own set of obstacles. This potential change in deployed nuclear deterrence may have unintended consequences for the current global nuclear posture. When dealing with strategic nuclear forces, deterrence can quickly be misinterpreted as an existential provocation—much more so than with changes in conventional forces. In other words, if the British nuclear forces had to be redeployed elsewhere, how might Russia respond?

Moreover, given the return to great power competition, Russia and China may see a newly independent Scotland as ripe to court with financial loans, investment, and activities. Even if Scotland does not take the bait, this could increase the geopolitical tension within the NATO alliance. NATO has already seen how Turkey’s acceptance of Russia’s S-400 missile system impacted the alliance and the deployment of other systems such as the F-35. Perhaps it would be in Russia’s interest to offer cheaper, next-generation weapons to Scotland to further sew mistrust amongst the allies. At any rate, NATO is on guard for Russia’s attempt to disaggregate the organization—which would most likely delay Scottish membership into the alliance.

Chinese financial courting may prove to be even more problematic, especially if it decides to fund some aspects of an independent Scotland. Although Scotland does have considerable stores of natural gas in the North Sea area, current joint ventures and business contracts with UK firms would have to be honored. This could limit Scotland’s ready access to capital in the near-term and present a potential opportunity for Scottish-Chinese joint ventures. China is feverishly buying up strategic infrastructure, and ports seem to be a favorite amongst the Chinese Communist Parties’ investment strategy. There is already worrisome precedent in NATO’s backyard. The Greek port of Piraeus was taken over by the Chinese company COSCO in 2016. While some welcomed the 600 million euro investment, which created 3,000 jobs, others viewed this as a “trojan horse.” Although many of these investments simply illustrate the one-sided aspect of the financial arrangement, alarmingly, many of these purchases also have military implications. For example, China’s acquisition of the deep-water port in Djibouti may accommodate its emergent fleet of aircraft carriers.

As nations compete for increasingly limited resources and spheres of influence, geographic areas that were once considered less important are gaining prominence.

Geopolitical implications must also be examined. As nations compete for increasingly limited resources and spheres of influence, geographic areas that were once considered less important are gaining prominence. Moreover, as weapons capabilities—particularly those designed to increase stand-off and limit force projection, mature nations must maintain alternate transit routes. The Greenland -UK Gap, also known as GIUK (Greenland, Iceland, and the UK), is a meaningful waterway currently dominated by NATO members. The strategic transit routes around Greenland, Iceland, the United Kingdom, and the Faroes Islands fall within the zone of NATO members: Denmark, Iceland, and the UK. This area was seen in a more crucial light as Russia began increasing its submarine force intended for northern waters.

In response to growing concern over these key sea lanes, NATO stood up a new command in September 2020. The Atlantic Command, headquartered in Norfolk, Virginia, “will ensure crucial routes for reinforcements and supplies from North America to Europe remain secure,” according to NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg. As Russia and China develop weapons that limit NATO’s ability to project power, alternate supply lines are increasingly important.

The Arctic itself has become more contested. This area is of increasing importance to the Russian military “as it renewed efforts to rebuild its military infrastructure and expand its capabilities in the Arctic and engage in provocative actions against the West.” Russia is building up in the region and testing potentially game-changing new weapons, including the Poseidon 2M39 torpedo allegedly designed to create “nuclear tsunamis for the coastal United States.” An independent, non-alliance member Scotland could serve as a vulnerability in the NATO armor in both the GIUK and Arctic areas.

In addition, a Scottish-free United Kingdom would need to readjust its defense spending and this could impact NATO capabilities. At the NATO Summit in Wales in 2014, the Alliance members pledged to increase their defense spending to 2% of their respective GDP’s, “a view to meeting NATO capability priorities.” This goal is intended to be reached by 2024 by all members. The United Kingdom is estimated to contributing 2.32 % and thereby already exceeding the target. Britain just recently announced its largest increase in defense spending since the Cold War, with money earmarked for shipbuilding, space, cyber, research, and other sectors over four years. As British defenses evolve more robustly, so do NATO’s. However, if Scotland were to become independent, funding may need to be repurposed. Relocation of numerous UK’s defense assets, not just the Trident system mentioned earlier, would be prioritized. There are shipyards at Govan and Rosyth. The Royal Air Force is based in Lossiemouth. In terms of defense enterprise, British ships are built north of the border and relocating this south would be daunting. All these relocation expenditures would cost substantial sums of money, thereby diverting funds from the previously intended “renaissance in British military capability.” Although, Britain might still be spending above the 2% target levels, the funds would not be advancing the alliance’s capabilities, only repositioning them.

Although focusing on a hypothetical situation, this paper nonetheless highlights that there would be significant ramifications for NATO if Scotland were to become an independent nation. Scotland would not automatically be admitted as a separate member and would need to proceed through the accession process. NATO’s nuclear posture may be significantly affected, as the UK’s nuclear submarines would not only need to be relocated but also an independent Scotland might prevent nuclear weapons from ever entering its territory, even if aboard another NATO member’s vessel. Perhaps the UK and Scotland may stipulate that the defense apparatus, agreements, and arrangements would remain stable for years to allow for a deliberate transition, but this is not a certainty. Additionally, territory vulnerabilities would be exposed in the GIUK and Arctic areas. This might also create the conditions—particularly in a fiscally constrained environment—where NATO’s primary adversaries could attempt bilateral financial deals to disaggregate NATO’s unity further. Finally, this may set a precedent for other potential break-away regions such as Catalonia, Flanders, or even possibly Northern Ireland, which would most certainly look to see how Scotland’s transition impacted its national interest.

In short, if Scotland’s desire to rejoin the European Union causes many to heed that passionate call for independence by William Wallace, a sovereign Scotland could be considered problematic for NATO. NATO, in turn, must then listen to another famous son of Scotland, Robert Louis Stevenson, “Everyone, at some time or another, sits down to a banquet of consequences.” Scottish independence could have numerous unintended consequences for the Alliance, and the organization must be prepared for every eventuality.

Matt Hampton is a graduate of the AY21 resident class at the U.S. Army War College. He is an Army Reserve Military Intelligence Colonel with more than 30 years of service with multiple operational and combat deployments.

Ronald E. Hawkins, Jr. is a graduate of the AY21 resident class at the U.S. Army War College. In more than 2 decades at the State Department he has been a public affairs officer at the U.S. Embassies in Kampala, Uganda, Bucharest, Romania, and Khartoum, Sudan. Before that, he had assignments in Washington DC, Sarajevo, Reykjavik, and Algiers.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of State, the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

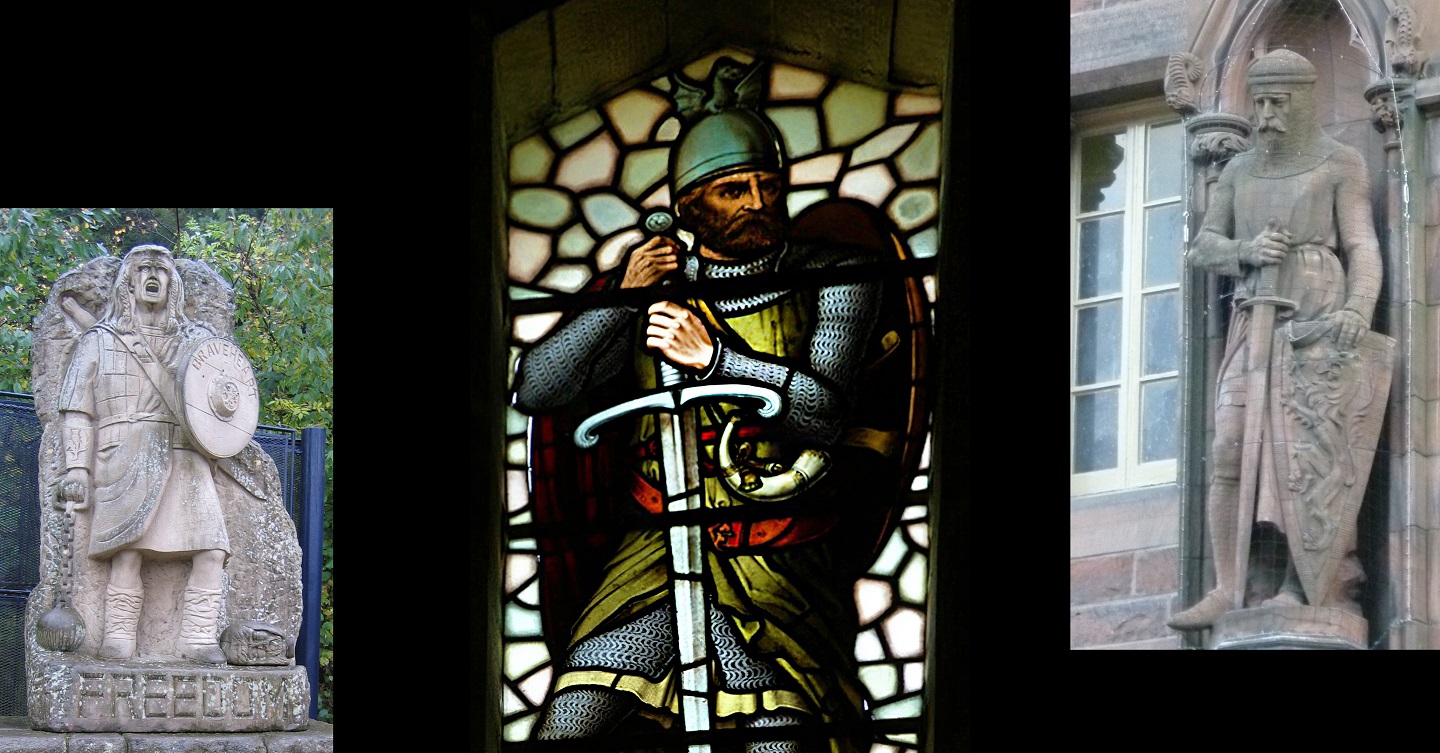

Photo Description: (L) Tom Church’s statue “Freedom” near the Wallace Monument. (C) Wallace Monument, Stirling, Scotland – stained glass window, William Wallace (R) William Wallace statue by D. W. Stevenson, Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh

Photo Credit: All photos via Wikimedia Commons (L) Rudolph Botha (C) Otter (R) Kim Traynor

Should the reason why Scotland might vote for independence, now as opposed to earlier, be understood from the following perspective:

a. The Britons, before Brexit, saw national security more through the lens of economic liberalism — an approach that considers that — in order to prevail and survive in the world today — a nation must be prepared to make such political, economic, social and/or value changes as are needed — this, so as to provide that one’s nation might maintain its internationally economic competitiveness. Scotland, for its part, agreed with this line of national security thinking. Whereas:

b. The Britons, after Brexit, saw national security more through the lens of abandoning the economic liberalism approach to national security; this, given the political fallout from those who were adversely effected by the political, economic, social and/or value changes that economic liberalism required. Scotland, for its part, disagrees with this new line of national security thinking (or should we call it, more correctly, group security thinking?); this, given that the Scottish people (a) still see national security more along economic liberalism lines and, thus, (b) are still willing to make such political, economic, social and/or value changes as are needed to achieve and support same.

Question: In the mid-19th Century, did not such nations as the U.S., Japan and China face similar “modernize or die” challenges? In those cases, the U.S. and Japan choosing to embrace economic liberalism, and the significant changes required by same. (As to the U.S. and Japan’s such “achieve change” missions, both the U.S. and Japan would ultimately need to apply military force — in this case — against certain of their internal, conservative/no-change adversaries?)

This, while China would attempt to achieve national security by refusing to change; relying, instead, on such things as “conservative values.” (As to this such “refuse change” mission, China would ultimately apply its military forces; in this case, more against external adversaries?)

(And as we all know, [a] these very different approaches to national security [b] had very different results.)